Take the Trail

Start at the corner of Frome Road and Victoria Drive, next to Botanic High School.

This Trail is on the traditional land of the Kaurna people. First Nations people are advised that this Trail Guide contains the names and images of persons who have died.

1. Overview

2. First Creek Garden

3. Adelaide Zoo

4. Albert Bridge

5. Re-vegetation along river

6. Playtypus re-wilding

7. Sculpture Park

8. Sir Doug Nicholls Bridge

9. Kaurna connection

10. Original flora

11. Police paddock

12. Salvation Army

13. An arboretum

14. Speakers Corner

15. Flying fox colony

16. Frome Park

17. Botanic High School

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 2.8 Mb)

1. Overview

At the starting place, on Frome Road, opposite Victoria Drive, (location #1 on the map above) there are several large English elm trees; and two very large Norfolk Island Hibiscus trees.

Park 11 is a very large area – stretching from War Memorial Drive in the north, to North Terrace in the south.

This Park also stretches from Hackney Road in the east, to Frome Road in the west.

Within that big area, Park 11 has been carved up into sections. The carveup started as early as 1844 and continues today.

Different parts of Park 11 have been used for many things OTHER than Park Land, with various uses, changing over the years as you will find out on this Trail Guide.

The sections of Park 11 include the Royal Adelaide Zoo, the Botanic Garden, Botanic Park, the small Frome Park, as well as the land that the State Government calls “Lot Fourteen” (that is, the site of the former Royal Adelaide Hospital) as well as the National Wine Centre, and the expanding Botanic High School.

The various parts of Park 11. This Trail Guide focusses predominantly on the parts that remain Open, Green, Public.

This Trail Guide does not cover all of Park 11. To keep within a two-hour window, this Trail Guide omits “Lot Fourteen” (the old Royal Adelaide Hospital site), the National Wine Centre and only skirts around (does not enter) the Zoo. It also omits the Adelaide Botanic Garden, which is covered in a different, separate Trail Guide.

The route for the Trail Guide is about three kilometres, and is likely to take about two hours.

Most of the route is on paved pathway but it also traverses Botanic Park, which might be wet or muddy if it’s recently rained.

There is no name for all of Park 11 other than “Park 11”. However, some parts of Park 11 have been called “Tainmuntilla” which is a word in the Kaurna language that refers to edible Mistletoe, a parasite that grows on River Red gum trees. Sometimes Botanic Park has also been called Tainmuntilla.

This Trail Guide follows the naming conventions of the Adelaide City Council, which has control of the strip of land along both sides of the River Torrens. The Council calls that part of Park 11 “Mistletoe Park” or “Tainmuntilla.”

From here, walk north along the Frome Road footpath to a bridge over a creek, flowing beneath the road.

2. First Creek Garden

Pic: Sally McTiernan, Google maps

As you walked along the Frome Road footpath, you would have seen a sign indicating First Creek Garden.

First Creek is one of five tributaries flowing into the River Torrens across the metropolitan area.

First Creek flows down the Adelaide Hills from Cleland Wildlife Park near Mt Lofty, through Waterfall Gully, Hazelwood Park, Tusmore Park, under Hackney Road, then into and through the Adelaide Botanic Garden, ending up here in First Creek Garden off Frome Road.

First Creek discharges into the River Torrens/Karrawirra Pari, on the other side of Frome Road.

In Kaurna language the river is called Karrawirra Pari which means “river of the Red Gum Forest.” This refers to the dense eucalyptus forest that used to line its banks. This Trail Guide will include a visit to an ‘original flora’ River Red Gum tree.

A pedestrian bridge over First Creek, in First Creek garden, off Frome Road.

From here, walk north along the Frome Road footpath to the pedestrian traffic lights near the Adelaide Zoo.

3. Adelaide Zoo

.

Here at the traffic lights you can see several trees with odd bulbous trunks. They are Bottle Trees (Brachychiton rupestris) native to Queensland.

These trees can grow up to 25 metres high with their water-rich, bulbous trunks eventually reaching a diameter of over 2 metres.

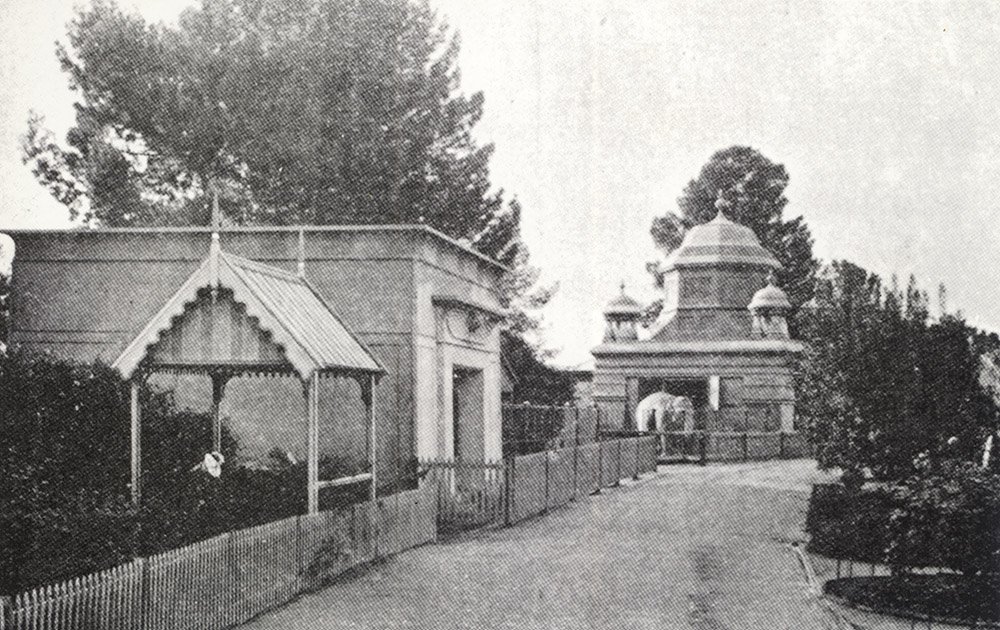

The Royal Adelaide Zoo occupies eight hectares of Park 11. It is Australia’s second oldest zoo and was opened to the public in 1883.

The modern entrance precinct to the Zoo was constructed in 2010. It aimed to dispense with the traditional boundary between the Zoo and its surrounds and provide a green area in which people can relax and enjoy this area next to First Creek.

A Queensland bottle tree off Frome Road outside the Royal Adelaide Zoo.

The Zoo is operated by a not-for-profit organisation which uses the trading name “Zoos SA”. Its official name is ‘The Royal Zoological Society of South Australia’. After the Society was set up in 1878, it took five years of lobbying to get the land removed from Botanic Park, the Zoo approved, and then built.

When the organisation was first established it was called “The Acclimatisation Society of South Australia.” Before the Zoo opened they put the word “Zoological” into their name, so that it was the “Acclimatisation and Zoological Society”. 49 years after its founding, in 1937, they received permission to put the word “Royal” in front of their name, and at that stage they dropped the word “Acclimatisation”.

When the Zoo was established in 1883 it was modelled on the major European zoos of that time, particularly, Regents Park Zoo in London.

There are a number of historic heritage-listed buildings within the Zoo grounds. Those buildings include the former elephant house, the head keeper’s cottage, a rotunda from the 1880’s, and the original entrance gates off Frome Road.

The first three directors of the Adelaide Zoo were three generations of the Minchin family – Richard, his son Alfred and his grandson Ronald – spanning the zoo’s first 50 years. The entertainer Tim Minchin is a direct descendant.

In the financial year ending 30 June 2023, Zoos SA reported revenue of $38.6 million. This included $7.7 million of Government grants with most of the rest coming from admissions and annual memberships ($29 million). The Zoo needs a large public subsidy to keep operating. The site itself might also be characterised as a public subsidy because it is a site that is taken from Park 11 of your Adelaide Park Lands.

Revenue from Zoos SA includes not just this Zoo but also revenue from Monarto Zoo. In 2022-23 ticket sales at this Zoo were $7.8 million, with a further $4.3 million coming from ticket sales at Monarto Zoo.

This Zoo is the most popular pay-to-enter tourist attraction in Adelaide, but not nearly as popular as the Botanic Garden.

In 2024, a one-off pass to enter this Zoo on one day only, was $42.50 for an adult, $31.00 student/concession, or $22.50 for a child aged 4-14. Family passes were $107.00. If you were going to come more than once in a year, or to visit both this Zoo and Monarto Zoo within one year, it would be cheaper to purchase membership of Zoos SA.

From here, walk north along Frome Road, and stop in the Zoo’s trades entrance or driveway, just before you get to the Bridge over the River Torrens.

4. Albert Bridge

Just before you cross over this bridge, look down over the edge towards the River. You can see the River Torrens linear pathway – a commuter route for cyclists and pedestrians. There is a sealed track on both sides of the River. In a few minutes this Trail will take you along the path on the opposite side of the River. But first a few words about this bridge.

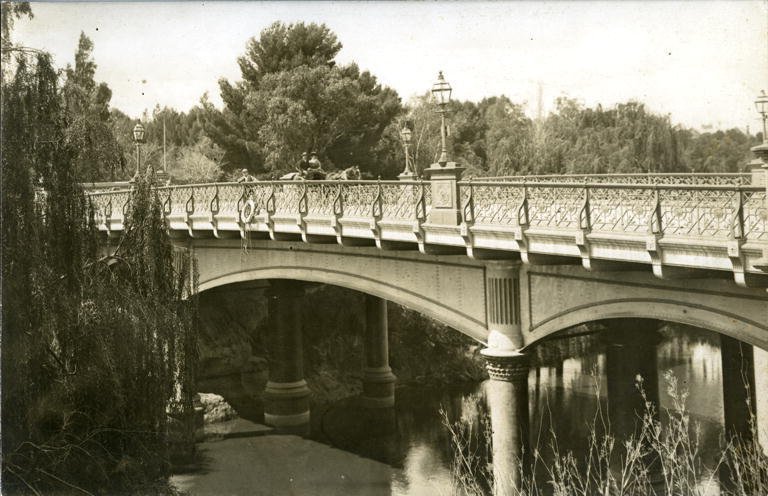

This Bridge is on the State Heritage register. The bridge is named after Queen Victoria's husband Albert, but was built in 1879, some 18 years after Prince Albert died.

There was an earlier bridge, close to this site (just a bit further downstream) but it was destroyed by flood in the mid-1800’s. That forced all traffic over the Torrens to go across the City Bridge in King William Road. It didn't take long to recognise that a single bridge was inadequate so in 1871 this “new” crossing was planned just slightly upstream from where the old one had been flooded away. However even back then, it was a long time (eight years) between the concept and the reality.

Eventually, the construction of this bridge greatly improved communication and transportation of goods between northern and southern Adelaide.

Opened in 1879, the bridge was constructed from iron brought over from the UK but constructed here. In 1879 construction cost £9,000. (That is, about $1.4 million dollars in today's money, a bargain).

Originally it had timber decking but in 1933 that was replaced with reinforced concrete which was again replaced in the 1980s.

In the year 2000, guard rails and improved lighting were added to improve safety while retaining the bridge's gracious historic features.

Now cross over the bridge, and follow the footpath alongside War Memorial Drive, with the river in view on your right. Stop where the path dips down to the river bank level, and there is a picnic table and lawn alongside the river.

5. Re-vegetation along river

On the way to this spot you might have noticed that the river bank has been stabilised with hundreds of gabions. A gabion is a cage, cylinder or box filled with rocks, concrete, or sometimes sand and soil for use in civil engineering, road building, military applications and landscaping.

This work was undertaken in 2017 to stabilise the river bank because at that time it was feared that the footpath was in danger of collapsing. The contractors employed by the City Council also undertook some revegetation around their engineering works.

This spot is the heart of Mistletoe Park / Tainmuntilla. The revegetation here has been going on for far longer than just since 2017. In the 1980s a great deal of effort was done along the length of the River Torrens in metropolitan Adelaide to create what we now refer to as the River Torrens Linear Park. The entire linear park stretches from Athelstone in the north-eastern suburbs, all the way to Henley Beach: some 38 kilometres.

Mistletoe Park is just one segment of that very long and beautiful Linear Park. You will notice a “native bee hotel” set back from the picnic area. Native bees are solitary and need tiny holes to nest, not large hives. They are very important for pollinating native plants, but fairly poor at producing honey! There are at least three other native bee hotels in your Adelaide Park Lands.

The City of Adelaide’s long term goal is to restore Mistletoe Park vegetation to the way it would have been before European settlement. That is, not a dense forest, but “Open Woodland”. Achieving that goal requires two things – planting locally-native species but also removing non-native species including those identified as “woody weeds” or invasive species.

In 2018, environmental consultants identified River Red Gums and two species of reeds as the only substantial ‘remnant’ native vegetation left in this area. They emphasized the importance of fallen logs and leaf litter in the understorey, which you can see has been supported to be part of this revegetated area. These elements provide shelter, refuge and living space for frogs, insects and spiders which, in turn, represent food for larger animals, including birds and larger reptiles.

The revegetation that has occurred here were acknowledged in a 2024 City Council report, which identified this area as one of seven “Key Biodiversity Areas” in your Park Lands.

Walk a little further along the path, and look on the right-hand (riverbank) side, to locate a small inlet with safe ground on the riverbank.

6. Platypus re-wilding

Pic: Adrian Mann / The Guardian

The steep banks and the thick growth of reeds and weeds means there are few opportunities for people to actually get in the water. Nevertheless, occasionally people do bring kayaks here. The Popeye river boats do come upstream a little way, after passing underneath the Albert bridge.

Nevertheless, most people who come here are using Mistletoe Park simply to pass through. Runners, walkers and cyclists are heading to or from the City on their way to or from Hackney. For a lot of the way, the land on either side of the path is steep, or thickly vegetated.

That means that very few people actually get off the path and investigate the area around. One result of that is that the area on both sides of the river represents significant habitat zones for biodiversity.

Where the river channel is fringed with dense reeds, it offers nesting and feeding habitat to waterbirds and amphibians. Woody debris and rocks within the water provides many functions for aquatic species such as water-rat and native fish.

The natural obstacles create microclimates within the river, and protect small species from strong currents and predators.

Since 2018, the Council has approved removal of some introduced vegetation but there remains the opportunity to undertake a widespread removal program.

Up until the late 1880s, platypus were living in the Torrens, but the iconic aquatic mammal sadly disappeared from this river following changes made to the environment.

In more modern times, scientists have identified the platypus an an ‘umbrella species’ which boosts the health of the wider ecosystem of the waterway, benefitting other species, such as long-necked turtles and rakali, a native water rat.

Since 2021, there has been a State Government project intended to bring the platypus back to the River Torrens.

It’s statutory authority, Green Adelaide, was hopeful that, with the improvements achieved in restoring native vegetation, habitat and water quality to the river, the time might be right to make the “dream a reality.”

A scoping study released in July 2023 found a number of positive signs for the future of the platypus in the River, including a high level of aquatic macro-invertebrates for platypus food, low levels of litter-based pollution, improved water quality and suitable habitat for platypus.

Since 2023, Green Adelaide has been working on targeted revegetation works and a detailed translocation plan to reintroduce platypus to Karrawirra Pari. This includes addressing known threats including dogs, cats and foxes.

As the project progresses, Green Adelaide will be encouraging the formation of a Friends of the River Torrens Platypus Community Group and a Platypus Fund to help re-wild the River. If you’re interested, please go to the platypus section on their website and subscribe for updates.

Now walk a bit further along the riverbank until you come to some large public art works, or sculptures.

7. Sculpture Park

This spot is called the River Torrens Sculpture Park. It was commissioned in 1994 by Foundation SA (now Arts SA), and contains five sculptures that are supposed to “respond to their bushland setting and the linear nature of this part of the Park Lands, with the parallel elements of river and paths.”

“Co-Ordinate #1 – You are Here” by Steven Giles. Pic: https://www.experienceadelaide.com.au/

The first sculpture is called “Co-Ordinate #1 – You are Here” by Steven Giles. It’s made of granite and slate. It’s a reflective sculpture that frames a view of the river and invites people to sit down and consider their own relationship in time and space to this environment. It’s designed to capture a particular view looking through the stone portal.

The next one looks like a pyramid - it’s by Linda Patterson. It’s called “End Divided Paths”. It’s a mosaic made from slate, steel and concrete. It’s located as a symbolic meeting place for people of different cultures and different ages. The mosaic imagery is made from material collected from old dwellings and rubbish dumps along the banks of the river.

The engraving was done in 1994 by children in urban communities near the river. The surface has been treated with an anti graffiti finish. The divided paths are an important element in the work. The intention is that although the sculpture is intimate, it should be able to be seen from the main walkway to entice viewers to walk the divided paths.

‘River Markers’ – three galvanised iron sculptures by John Wood, use stylised versions of the surrounding landscape: one that is supposed to resemble a common black duck, another that represents two native fish (the big-headed gudgeon and the blue spotted goby) and the third that represents mative flora (river red gum leaves and flowers with kangaroo grass and rushes).

These species would have been found at this site prior to European settlement. The markers contain these images intertwined with symbols of the river. It was designed to be in clear view from both sides of the river. The galvanised steel was always intended to weather naturally.

Be sure to look down as well as around. There’s a piece called ‘Landline/Timeline’ by Philip Hind that’s set in the ground itself - running from the river, across the path and up the hill to the road. It’s made of granite, bronze, slate and concrete with aggregate.

It is an in-ground line that can be traversed with marker points at each end. The work helps the viewer reflect on the time the river has been flowing and the ancient archaeology and culture of the site. The artist intended that the sight-line should always be in view from War Memorial Drive.

There is a fifth sculpture a short distance away. Walk along the path, and stop at the final sculpture just past the pedestrian bridge. Made from stainless steel and bronze, by Chetana Andary, it’s called “Journey”. It was designed to bridge the pathway and symbolise the artist’s own individual journey involved in the transition from a traditional Middle Eastern culture to the values and aspirations of contemporary Australian society.

Now, walk back to the pedestrian bridge.

8. Sir Doug Nicholls Bridge

When it was built in 2010, this was the first new pedestrian crossing built over the River Torrens in Adelaide for 73 years (i.e. since 1937). Another bridge followed shortly afterwards to link Elder Park to Adelaide Oval. Before this bridge was built, this section of the river on the Park Lands trail was considered unsafe, because it was so secluded. These days the paths on both sides of the river are very busy.

This bridge is called the Sir Douglas Nicholls Bridge, named after one of the most famous aboriginal Australians of the 20th century. Sir Douglas Nicholls was born in 1906 and in his young years he was both an aboriginal activist (a pioneering campaigner for Aboriginal reconciliation) and also a VFL footballer. He played for Fitzroy in the VFL, for six seasons, in the 1920’s which was the top competitive level long before there was an AFL.

Later, he was the first Australian Aboriginal to be knighted, the first Australian Aboriginal to be appointed State Governor of any State or Territory, and the first Pastor of the Aboriginal Church of Christ in Australia.

Sir Douglas Nicholls was appointed Governor of South Australian in 1976 but had to resign due to ill health the following year. He lived for another 12 years after that and died in 1988.

Pastor Sir Doug Nicholls. Pic: National Archives of Australia: A6180

The bridge was designed and built by the company Oxigen. It was deliberately positioned midway down the embankment to provide isolation from traffic on War Memorial Drive and Plane Tree Drive, and to respond explicitly to predicted patterns of use for cyclists and pedestrians.

The primary materials of the bridge are three types of steel: weathering steel, stainless steel and galvanized steel – none of which require painting. Only the substructure is painted silver to provide a contrast to the water below. The deck is a composite system of galvanized web-forge steel mesh infilled with granolithic rubber softfall. The outer edges of the deck are left as open mesh, providing a slim and porous edge to allow drainage and views through to the water below. LED strip lighting is incorporated into the balusters.

The bridge won the Adelaide Prize for architecture in 2010. The judges called it "an object of art as much as an element of public infrastructure".

From here, cross the bridge, and turn right. Then walk up the slope to Plane Tree Drive, and cross over at the pedestrian crossing to enter Botanic Park. Walk in a south to south-easterly direction direction and stop at a grass clearing in the centre of the Park, near gum trees.

9. Kaurna connection

You are now in Botanic Park. This green oasis, just a short walk from the Adelaide CBD, is one of the most important open, public and green spaces in Adelaide.

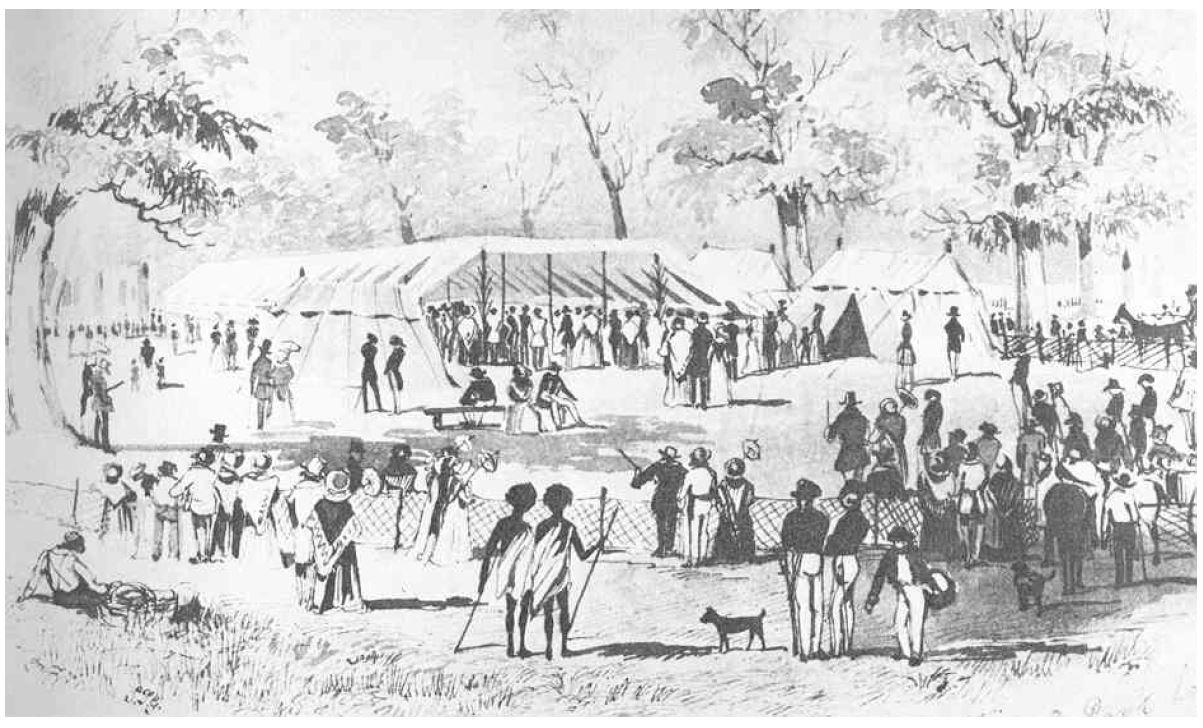

We speak about the beginning of the Adelaide Park Lands in 1837, but of course that date means something very different to the original inhabitants of this area, the Kaurna people. Botanic Park, like the rest of the Adelaide Park Lands, of course had an earlier history.

For generations before Europeans arrived, Kaurna people and hundreds of Aboriginal people from Encounter Bay, the Lower Lakes and the River Murray used to gather in camps in the areas that were later designated Park Lands, especially along the River where water was available and there was tree shelter and food.

Even after colonisation or invasion and right up until the turn of the century in 1900, areas around and within the present Zoo, Botanic Gardens and Botanic Park continued to be occupied by Aboriginal camps for ceremonies, burials and other culturally significant activities.

There are numerous records from the 1850s that Kaurna people performed what the Europeans called “corroborees,” putting on shows for the public in Park 11.

Detail from Alexander Schramm: 'Adelaide, a tribe of natives on the banks of the river Torrens' 1850

The local aboriginal people favoured this Park, over the other Parks in the Adelaide Park Lands, for a very simple reason - the trees.

In the first three decades of colonisation, European settlers stripped your Park Lands of trees. Nearly every single tree in the Park Lands was cut down for firewood, fencing and building materials.

It was only here, in what became known later as Botanic Park, that some of the original tree cover was retained, including river red gums. So the Kaurna people gathered here – simply because it was the one area that resembled the Adelaide plains that they used to know before the Europeans arrived. The proximity of the river would also have been a factor.

The River Torrens (Karrawirra Pari) was an essential economic and sustenance conduit and place for the Red Kangaroo Dreaming, in Kaurna culture. Women and children would dive for cockles in the river, using a net bag.

Unlike in other parts of the Park Lands, the colonists did not make an effort to drive out Kaurna people from this site. They at least tolerated, if not encouraged the use of Park 11 as a camp site. In fact, in the 1850’s, there was an annual distribution of rations and blankets to Aboriginal people here, in what was then called the “Police Paddock”. It happened each year, on Queen Victoria’s birthday, 24 May.

Walk closer to Plane Tree Drive to within sight of the giant Moreton Bay Fig Trees. Stand between these and the very old River Red Gum (marked ‘Original Flora’) near the eastern end of the stand of trees.

10. Original flora

Visitors to Botanic Park and the adjacent Botanic Garden cannot help but be impressed with the very old Moreton Bay Fig trees, with their huge trunks and gnarled buttress roots. This Fig tree’s scientific name is Ficus macrophylla. It is native to eastern Australia.

But before these old Figs and the nearby Plane Trees were planted in the 1860s, and even before Europeans first arrived, this tree was already living here.

It’s a very old River Red Gum - several hundred years old . It’s one of a few remaining River Red Gums in Botanic Park and the adjacent Botanic Garden, which are labelled ‘Original Flora.’ That means these individual trees were already living here on Kaurna land before Europeans arrived, and before the colony of South Australia was created in 1836.

Its survival can be attributed to the first Director of the Adelaide Botanic Garden, George William Francis, whose made the decision to retain good specimens of the original River Red gums in and around the Botanic Garden, carefully plotting them on his plans of 1855.

This river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) in Botanic Park is believed to predate European settlement. Photos: Ingrid Kellenbach.

The River Red - Eucalyptus camaldulensis - is amongst the most iconic of Australia’s trees. Full of character and found across most of Australia, In 2022, the River Red was voted the ABC People’s Choice as Australia’s favourite tree.

As water lovers, they grow along rivers, creeks, waterways and in floodplains. In an ABC-TV Catalyst documentary exploring Australia’s favourite trees, they were described as “the diviner of our landscape, plotting the watercourses all over our arid continent.”

These trees can have very long lives and may reach 1,000 years of age.

Older specimens, like this, almost always develop large hollows which can take centuries to form. The hollows provide refuge for birds, mammals and reptiles. And the nectar from their summer flowers is very important for honey production.

# Of the original River Reds saved by Francis, about six are still living - two in the adjacent Adelaide Botanic Gardens and four here in Botanic Park.

Now, walk in a north westerly direction beyond the Moreton Bay trees to stand in the centre of the park.

11. Police paddock

.

In the 1870s, there was a push by the influential Royal Agriculture Society to access land on which to commence an annual agricultural ‘show.’

The Society had their eyes on this land adjacent to what was at the time, the relatively new Botanic Garden.

However, in the 1870s, this area had other occupants.

In addition to ongoing Kaurna use of this land, part of this site had been used, since 1837, by the colonial police force, to keep their horses. It was known as ‘Police Paddock.’ But there was much more land in this park in the 1870s than the police had required for their horses.

The Agricultural Society won out, and established their showground in this Park. Later on this Trail, you will come to the site in Park 11 that was occupied by Showgrounds, for many decades.

The police horses were moved, from here, to another area of your Park Lands … to Park 27, Bonython Park/ Tulya Wardli (Park 27) to be amongst the colony’s historic first olive grove, where they stayed until 2024. They were then moved to a new site at Gepps Cross.

Now, walk to the centre of Botanic Park to find a memorial stone which marks the location of the first successful Salvation Army meeting in Australia.

12. Salvation Army

This is a memorial stone to commemorate the location of the first successful Salvation Army meeting in Australia. It was 1880 and the Salvos had commenced in East London just 15 years earlier.

Two young men, Edward Saunders and John Gore, had already been holding regular open-air meetings in Light Square where they had been meet with derision from the crowd.

But they met with much greater success when they decided to hold a larger meeting here in Botanic Park from the back of a greengrocer’s cart.

It was a time of economic depression, with nothing but charity and government rations for the large number of unemployed to rely on.

At that meeting, Gore is reputed to have taken the first step in their social welfare mission, declaring that ‘If there is any man here who hasn’t had a meal today, let him come home with me’, after which, it was claimed that Saunders led the crowd in singing a hymn.

The Salvation Army’s dual mission of evangelism and social welfare was now begun in Australia, the movement grew rapidly, particularly during the 1890s Depression and by the time of the Great Depression in the 1930s, homes for unmarried mothers, released prisoners and the unemployed were established, in addition to hospital visitation, tracing missing persons and distributing clothing.

Location of the Salvation Army memorial plaque in Botanic Park. Pic: Loine Sweeney

Pics: https://monumentaustralia.org.au/ (left) and https://www.facebook.com/TheSalvationArmyAustralia (right)

Now, walk southward to stop within view of the Plane Trees in Plane Tree Drive.

13. An arboretum

These days Botanic Park is one of the best places in Adelaide to come for a picnic, amongst the trees.

34 hectares of Park Lands that we now know as “Botanic Park” were acquired by the Botanic Gardens in 1874.

Botanic Park, then and now, represents 5% of the entire Adelaide Park Lands.

By the 1870s, the Adelaide Botanic Garden had a new Director, Richard Schomburgk, and it was his vision to transform this area of Park Land into an ‘arboretum’, a park devoted to trees. He also envisioned a carriage drive lined with shady trees and wide expanses of grassed areas.

Schomburgk focussed on European and North American forest species, but also brought in Moreton Bay Figs and other Australian species.

Today, Botanic Park’s tree collection still contains many of the early plantings such as the gloriously shady Plane Trees planted along Plane Tree Drive in 1874. By the end of 1877, more than 9,000 trees had been planted in Botanic Park,

Half of the Plane Trees planted in the 1870s were removed in the 1960s to relieve overcrowding, because they had grown so large and wide.

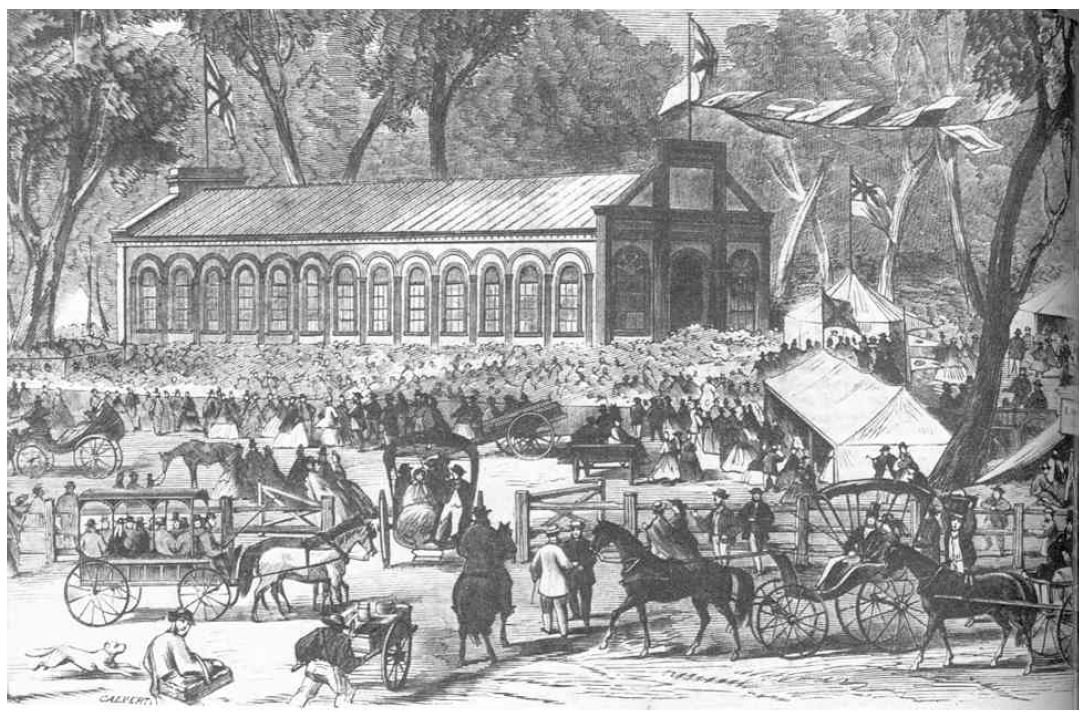

In 1884, Botanic Park and Plane Tree Drive were officially opened. Almost 19,000 carriages and another 1,700 horse riders were reported coming here in one year (1889) to enjoy the growing beauty of the Park.

Today, Botanic Park’s tree collection still contains many of the early plantings, such as pine species from the Mediterranean which are planted along Hackney Road

As you walk around the Park, you will come across a wide range of tree species, including some recent new plantings, which you can spot by the green plastic sleeves protecting and guiding the growth of the saplings. These include Gingko Biloba and the majestic, Himalayan Cedar (Cedrus deodara).

If you’d like to know more about the diverse range of trees, the Botanic Gardens volunteer guides give free, weekly tours of Botanic Park on Monday afternoons from 2pm - meet just inside the Friends’ Gates.

Unlike most of your Park Lands, this part of Park 11 is not managed by the City Council, but by the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium board, which is part of the State Government’s Environment Department.

Parts of Botanic Park are also commonly hired for open air ticketed commercial concerts and other events, such as the annual Moonlight Cinema and the world music festival, WOMAD.

From here, walk further west to stop at a location with the Zoo entrance in view.

14. Speakers Corner

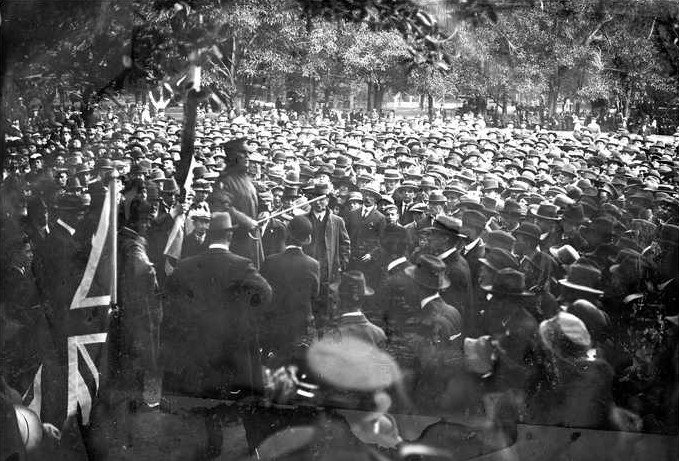

About a decade after the Salvos set up in Botanic Park, it also became a forum for public debate on current affairs of the day.

Records show that from the 1890s, ringed areas were set aside within the Park for public speaking on Sunday afternoons. These attracted large audiences to hear debate on all manner of issues.

The nineteenth century was a period of great social change and this leafy park became very popular with those interested in hearing political debate, attracting crowds of up to 5,000 people.

While many of the speakers were from a wide range of political groups and parties, others debated issues ranging from consumer protection, trade union concerns and unemployment to anti-conscription, alcohol temperance, pensioners’ concerns.

One debate in 1915 grew very heated when a speaker from the “Australian Peace Alliance” was attacked by a group of soldiers and had to be escorted from the park to the police barracks for his own safety.

While there was considerable freedom of speech in the park, a speaker in 1939 promoting fitness took things too far when he called a police sergeant in the crowd big and fat, and was fined 2 pounds ($4).

Organisations wishing to speak in the park had to apply to the Botanic Gardens’ Board for a license. Each speaker had to be named and approved and, while licenses were rarely refused, police reports about applicants were sought before approval was granted. Successful applicants were then allocated specific locations from where they could speak.

In 1951, the area for public debate was relocated on the other side the small bridge over First Creek, where it became known as Speakers’ Corner. Some of the original seats are still there.

Walk over the historic little First Creek bridge and then walk a little eastward until you can look northwards towards a lap of creek-side land under tall trees.

You can see three rows of historic seats forming a half-ring (sometimes obscured by tall grass). These are the last remaining seats of what became known, from the early 1950s, as ‘Speakers’ Corner.’ It was actively used for outdoor oratory and campaigning and remained an important element of Botanic Park life until the 1970s.

Speakers included the young, but ambitious, Donald Dunstan when he was still a Labor candidate for the seat of Norwood. He went on to become one of South Australia’s most notable and longest-running Premiers during the 1970s.

When television took off in Adelaide from the early 1960s, the use of Speakers Corner slowly declined.

From here, stand near one of the tall trees hanging with bats.

15. Flying fox colony

As you can hear, and see, and smell (!) this western end of Botanic Park hosts tens of thousands of climate change refugees: the grey-headed flying foxes, which are sometimes called ‘fruit bats.’

You can see them up in the tree tops hanging upside down from the branches to roost during the day, usually with their wings folded or wrapped around their bodies. They are one of the world’s largest bats, weighing in at 700 grams. This stand of trees erupts at sunset as this huge colony of megabats takes to the sky for their night feed.

Males use loud calls and strongly-scented secretions to mark their mating territories. Females also vocalise to find their young within the camp. They are also intelligent and social animals, gathering in large numbers at their roosts, not only because of their social nature but also for protection from predators.

Pic: Chris Katona

Pic: Shane Sody

Until the year 2010, these mammals were only occasional visitors to Adelaide. That was a drought year in the eastern states and it forced grey-headed flying foxes to head south-wards looking for food. In the year 2010, tens of thousands of them arrived here, and others turned up in other unexpected areas such as Tasmania and islands in Bass Strait.

This is their only “camp” in the Adelaide region, although a newer smaller colony has set up near the South East regional town of Millicent, and camp sites can be used regularly for long periods of around 100 years.

Their preferred foraging range is about 20 kilometres. The flying foxes leave the camp around dusk each evening and return before dawn. They feed in the tree canopies, on blossom, nectar (including gum nectar) and fleshy fruit.

Colony growth was generally anticipated to stabilise when food resources became limiting and, until 2023 it was believed that this camp might have stabilised near the 20,000 mark. However the mild summer of 2023-24, and good resources saw the numbers surge to 46,000.

Pic: Miriam Amerygale

Green Adelaide’s urban biodiversity team leader, Jason Van Weenen says its been a steep learning curve because the population is both protected as well as being a challenge to infrastructure and industry - and as you can also see they are a challenge to the health of these trees.

If you visit parts of the River Torrens during very hot days in summer you might see flying-foxes gliding over the water, and dipping their bellies into the river. Then they land in nearby trees to lick the water from their wet belly fur. That is not typical behaviour – it’s an adaption to heat stress on those days.

Despite this behaviour, on some very hot days, bats literally fall out of the skies or fall out of the trees and land on pathways or grass.

They can carry diseases, with a range of health risks to humans. You can get very ill just from touching a bat. If you see a bat on the ground, call the City Council (Ph: 8203-7203) and ask for a Park Ranger. Trained professionals are vaccinated against the diseases they can carry and are able to safely handle and look after them.

Pics: Marjan Kaashoek

From here, walk south to pass behind Botanic High School. Stop when you have passed the school buildings and you have a view through to Frome Road.

16. Frome Park

There are so many buildings along Frome Road, and only a narrow sliver of green - the last remaining shred of Open Green Public Park 11 on this side of Frome Road.

The area between Frome Road and the Adelaide Botanic Garden has been lost as an Open Green Public Park, three times. First it was lost to construct a grand exhibition building, secondly to a large car park, and since 2017 it has been lost for a third time, to an expanding high school.

This was where the Royal Adelaide Show was located, from 1844 to 1925 – a total of 81 years. During that time, there was a grand Exhibition building here.

There was also an ugly metal fence along Frome Road. In 1925, the Show moved to a new location at Wayville, where it remains. The ugly tin fence remained, and wasn’t removed for another 11 years, in 1936. Soon afterwards the site was turned into a car park, for workers at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

Eventually, car parking was consolidated onto a smaller footprint – the multi-storey car park you can see today, and the land was belatedly returned to Park Lands in the 1980s.

The City Council was given control of this small patch and the Council decided to name it Frome Park.

Edward Frome was a British soldier and surveyor. He took over from Colonel Light in 1839 as the Chief South Australian surveyor. There are several things named after him: not just Frome Park but of course Frome Street, Frome Road here, and Lake Frome in the north of the State.

Edward Charles Frome (left) and Nellie Raminyemmerin (right)

In 2002 the City Council decided to give this Park a second name, a Kaurna name, and called it Nellie Raminyemmerin Park. Nellie was a Kaurna woman who was kidnapped from the banks of the River Torrens in 1844 and taken to Kangaroo Island to live with a sealer named John Wilkins, with whom she had seven children. Following his death in about 1860, she and her children were sent to the Point McLeay Mission (near Lake Alexandrina at the River Murray mouth) under the care of the Reverend George Taplin.

Some of Nellie Raminyemmerin’s descendants still live in the Adelaide area today. It’s a terrible story, not something to celebrate, but it is good that at least her name will not be forgotten.

In 2010, Frome Park was rehabilitated and replanted to form a green garden link between the western gates of the Botanic Garden and Frome Road. It created a beautiful symmetry between this Park and the large green forecourt directly over the road in the University of Adelaide.

It was a very pleasing initiative in the modern world to create a rare patch of green on the Frome Road border of Park 11; a new vista in Adelaide; and to restore built-over parklands so they were again open, public and green.

However the reclaimed green space has since shrunk, twice.

Walk back to stand behind Botanic High school.

17. Botanic High School

Botanic High School is another example of the State Government taking away Open Green Public park lands for its buildings. The High School was opened in January 2019, after a two-year construction process. On this site previously was a Uni SA building, the seven-storey Reid building.

Many people believe that the Park Lands are managed by the City Council. It’s true that the City Council manages MOST of the Park Lands – perhaps 80% or thereabouts. But various agencies of the State Government manage the rest. For example, West Terrace Cemetery in Park 23 is managed by the Adelaide Cemeteries Authority (a State Government agency). Botanic Park and the Botanic Garden are managed by the Environment Department.

And this plot of land, 7,300 square metres, is managed by the Education Minister.

But it is still part of the Park Lands. There is a legal document, the Park Lands Management Strategy that is supposed to be binding on both the City Council and the State Government, but the reality is that the State Government ignores the Management Strategy whenever it wants to build something on a Park Lands site controlled by the State Government.

It has a simple mechanism to by-pass Park Lands planning. The State Government simply changes the zoning of Park Lands.

This site was Open, Green, Public Park Lands until the 1960s.

This aerial photo from 1955 shows how the Botanic High School has been built over former Open Green Public Park Lands, in Park 11. Pic: Darian Smith

This part of your Open, Green, Public Park Lands has been lost in three stages, corresponding to the three separate towers of the Botanic High School.

First, a University building (what became known as the UniSA ‘Reid” building) was constructed on this Park in the 1960s.

The former UniSA “Reid” building, pictured in 2015 before it was transformed, doubled in size and expanded over Frome Park to become the Botanic High School by 2019.

The Park Lands Management Strategy 2015-25 called for the former Uni SA Reid building to be demolished and the land returned to Park Lands. However in 2016 the former State Labor Government disregarded that plan and simply approved more than doubling the size of the Reid building, to make it two towers instead of one, connected by a central atrium. In addition, they’ve put a large storage shed, the size of an aircraft hangar behind the school.

So now we have the Botanic High School on Park 11. It was opened for students in January 2019.

In 2022, just prior to the State election, both major political parties promised that if elected, a new wing of Botanic High School would be constructed on Frome Park / Nellie Raminyemmerin Park. The City Council later sold off the building site to the State Government, and construction was completed by 2024. The Park’s frontage to Frome Road has narrowed to become little wider than a pathway.

To complete the works, an avenue of gum trees was planted in 2024, and it is still possible to make your way through this narrow sliver of a Park from Frome Road to the western entrance of the Adelaide Botanic Garden.

Also, here at the rear of the High School there are still wetland features which are important for local birds and frogs, especially after rain has replenished the ponds.

From here, walk to Frome Road to return to the starting point of this Trail.

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 2.8 Mb)

All of our Trail Guides and Guided Walks are on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people. The Adelaide Park Lands Association acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future traditional custodians and elders of these lands.