Take the Trail

Start at the top of the hill – at the traffic lights at the south end of O’Connell Street.

This Trail is on the traditional land of the Kaurna people.

It’s 2km long. Allow about 90 minutes.

Part 1: Brougham Gardens /Tantutitingga

1. Introduction and Naming

2. History and Layout

3. Floral Clock, Flagpole and Time Capsule

4. Teddy Love Chair & St Ann’s College

5. Uniting Church & Rose Gardens

6. The trees of Brougham Gardens

7. Lincoln College

8. Western Corner

Part 2: Palmer Gardens / Pangki Pangki

9. Naming and History

10. Vedalia Beetle Seat

11. The Trees of Palmer Gardens

12. Doolette House & Kindergarten Union

13. Montefiore (Part of Aquinas College)

14. Roche House

15. Boyd House

16. Christ Church and Rectory

17. Bishop’s Court

18. Honeywill House

19. House and Stables ‘Duncraig’

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 1.5 Mb)

Part 1: Brougham Gardens/ Tantutitingga

1. Introduction and naming

.

This Trail Guide starts at the top of the hill – at the traffic lights at the south end of O’Connell Street.

The trail will take about 90 minutes to complete. Palmer Gardens and Brougham Gardens are known as Parks 28 and 29. The use of the numbers 28 and 29 helps to emphasise that Palmer Gardens and Brougham Gardens (like other Parks) are part of a larger whole, the entire Adelaide Park Lands.

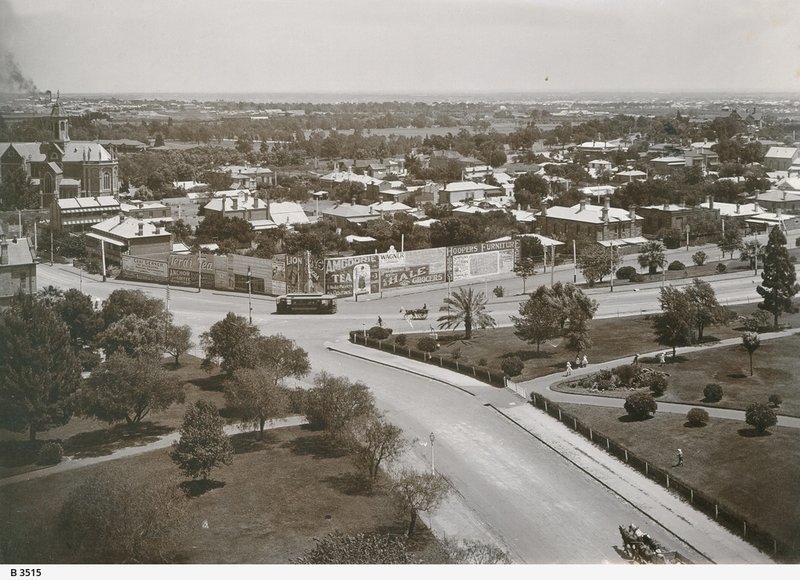

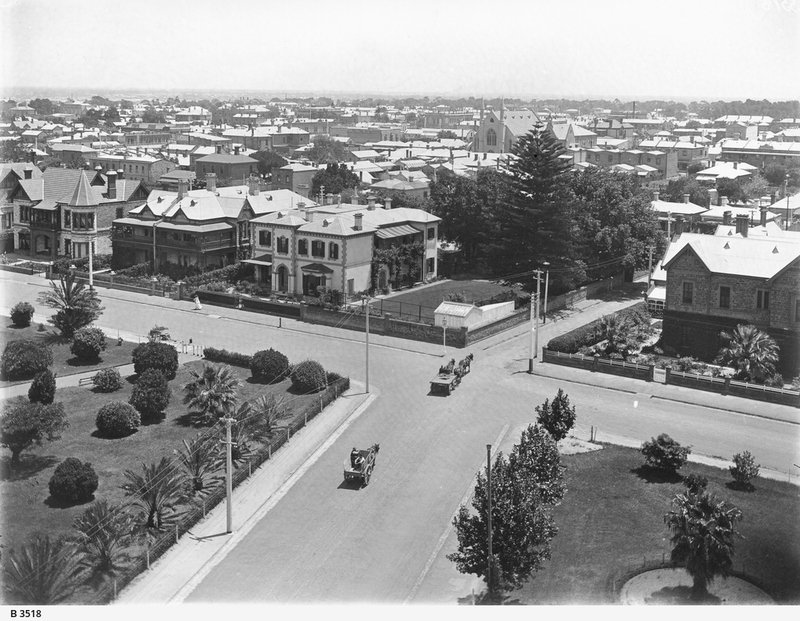

Brougham Gardens 1910 : Looking west from the Church tower, 1910 ~ Source: SLSA B-3521 ~ Creator: Gabriel Francis ~ Date: 1910

For more than 180 years these two garden areas have had a special role in the history and social culture of Adelaide.

The built heritage that surrounds these two gardens is also impressive, and on this trail we’ll view some of the late 19th and early 20th century mansions, once owned by the “who’s who” of Adelaide.

Brougham Gardens is named for Lord Brougham, who lived from 1778 to 1868. He was Lord High Chancellor of the United Kingdom and founder of the London University. He was a social reformer, who helped end the slave trade, and also promoted education for general population, with the “Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge”.

The Kaurna name is Tantutitingga, which means native lilac place. Native lilac (Hardenbergia violacea) has a wide distribution. It flowers during the depths of winter and is a sign of hope. This name has been adopted because of the gardens’ close proximity to the Women’s and Children’s Hospital where patients and their parents hope for recovery.

Native lilac (Hardenbergia violacea)

In 1972 Aboriginal people established a tent embassy in Brougham Gardens in support of an informal embassy that was started in the same year on the grounds of Parliament House in Canberra.

From this point there are two pathways that go down the hill towards the Women’s and Children’s hospital. The left-hand path is lined on both sides with English elm trees.

But for this trail, please choose the right-hand, lower path. This path goes past three Dutch elm trees (on your right) and several Canary Island pine trees, along with a huge Moreton Bay fig tree.

Stop where the path connects with another path heading off to the left.

2. History and Layout

Here at the path intersection, you are standing on what used to be a roadway. The footpath that runs north-south here, once was (up until 1972) a road called Bagot Rd.

In Colonel Light’s 1837 design for Adelaide, there was no King William Road. King William Street did not extend northwards past North Terrace. In Light’s plan, there was a road from the western part of the city up to Montefiore Hill, and another road from the eastern part of the city to North Adelaide that followed the course of what we now call Frome Road.

However, early settlers suggested that a central road, and a central river crossing was needed. The first King William Road bridge over the River Torrens was opened as early as 1839. That bridge enabled the development of North Adelaide.

But that 1839 bridge did not connect King William Road with O’Connell Street. It connected with Bagot Street which came up the hill, past this point. The road used to curve away to the right, up the hill, to connect with Lefevre Terrace.

14 years later, in 1853, a petition was presented to the Legislative Council, for a road to be placed through Brougham Gardens to connect the northern part of King William Road with O’Connell St, which was emerging even in the early 1850’s as a commercial precinct.

Brougham Gardens had already been cut in three by Bagot Street and Margaret Street. The new King William Road meant that the gardens were then cut into four segments, by Bagot Street, Margaret Street AND King William Road.

Nevertheless this Park retained its unusual shape. It has three corners, but it’s not a triangle. From the air, or on a map you can see it is in the shape of a boat’s keel, or an arrowhead. The arrowhead is pointing west-south-west. The tip of the arrow is on the other side of King William Road and almost joins onto Palmer Gardens.

Brougham Gardens is about 3.4 hectares in size. The road around, on every side, is called Brougham Place.

Although the Gardens were severed by King William Road, in the 1850’s, there was small return of Park Lands more than 100 years later. Bagot Road, where you are now standing, was closed in 1972 and became this footpath instead. In addition, Margaret Street through the Gardens was also closed, and all traffic had to go via either King William Rd or Frome Road.

Unlike many other parts of the Adelaide Park Lands, Brougham Gardens appears NOT to have been used in the 1800’s for grazing cattle. However, by the late 1870s it had suffered the same fate has other parts of the Park Lands, losing most of its indigenous vegetation. It was then fenced with white-painted timber posts and wire.

By 1900, Adelaide’s city gardener August Pelzer had transformed Brougham Gardens into a more formal Victorian style park, much as it is today, with a few palms and deciduous European trees, and extensive flowerbeds at points along the internal pathways.

Therefore, it is still today as it was in the late 19th century, a Victorian-era style public garden. It has several diagonal pathways and it’s framed externally by numerous two-storey Victorian era houses.

From this point, turn right and go down the hill towards the flagpole.

3. Floral Clock, Flagpole and Time Capsule

One of the main features of Brougham Gardens is this floral clock, installed in 1986 at the head of King William Road, on the spot where Bagot Road had been closed 14 years earlier in 1972.

The clock was the result of a donation on behalf of Andrew Penfold Simpson to honour South Australia’s 150th anniversary celebrations.

The mechanism for the clock was given by the Penfold Simpson family in memory of their son, who was killed in a car accident in 1983. The remainder of the clock was funded by donations from the Women’s Sesquicentenary Executive of the State’s 150th Jubilee.

The clock was started by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth on the 10th of March 1986.

It was still functioning in early 2017 but in 2018 was taken out of service for repairs. After five years, it was returned in working order in April 2023.

Next to the floral clock, a flag pole was erected in 2005 to commemorate the Centenary of Rotary International and the 90th anniversary of the Rotary flag. The flag pole usually flies the coat of arms for the City of Adelaide.

Beneath the flag pole is a time capsule that was laid in November 2005 by the Rotary Club.

The capsule was sealed in a granite cairn in October 2005 and is due to be re-opened after 50 years, in 2055. Thirty-two Rotary Club branches provided various articles for the capsule, although the details of its contents have been kept secret.

On both sides of the floral clock, both eastern and western sides, there is a large, elderly olive tree. Given their size, each one probably dates back to the 1850’s.

From King William Road, in front of the floral clock, walk along the footpath adjacent to the Women’s and Children’s Hospital until you once again reach a path intersection.

4. Teddy Love Chair & St Ann’s College

Just past the path intersection opposite to the Women’s and Children’s Hospital, you will find a park bench bearing a bronze plaque that refers to the Teddy Love Club.

The plaque and bench were donated in 2007 by what was then called the “Teddy Love Club” as a symbol of supporting and understanding for bereaved parents.

The Club has changed its name – it’s now called “Bears of Hope” still using Teddy Bears as symbols. It offers support to parents who are bereaved with either miscarriage or infant mortality.

This site was chosen for the plaque because of course it overlooks the Womens and Childrens Hospital. Many patients and families come to spend time here in Brougham Gardens.

From this point, looking east, you can see a collection of buildings behind a red brick wall. These buildings are known collectively as St Ann’s College.

The oldest buildings on this site were erected in the late 1920’s. Originally, before 1939 it was two private residences.

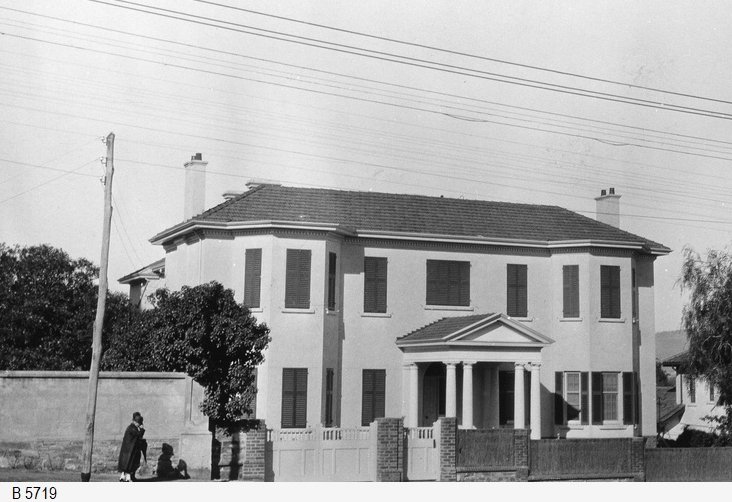

The original property at 187 Brougham Place was a house, owned by Mr Sidney Wilcox [See pic B 5719]. After his death in the 1930’s it was bequeathed to become residential accommodation (originally only for women) affilliated with the University of Adelaide.

It opened to students in 1947 after the Second World War. The college also includes an adjacent building around the corner in Melbourne Street.

Later, St Ann’s College acquired the adjoining premises at 191 Brougham Place, with land extending around the corner into Melbourne Street (See photo B 5797) and in 1961 a spacious dining hall and common room were built.

The first principal of St Ann’s college was New Zealander, Dr Mary Harding between 1947 and 1952.

Between the 1960s and 1970s, there were substantial additions and alterations to the college buildings. In 1973 the College became co-residential, and there are now approximately equal numbers of male and female students.

The site includes a principal’s residence and a tennis court on the corner allotment. It can cater for a maximum of 185 students, living in single rooms, some with ensuites and some with shared bathrooms. Meals are provided.

The site is a State Heritage Place. From this point, walk up the hill to the Church.

5. Uniting Church & Rose Gardens

This Greco-Italian style building is known today as the Brougham Place Uniting Church. However when the foundation stone of this building was laid in 1860 it was known as a ‘Congregational’ Church.

The founding of Adelaide in 1837 was partly driven by a desire for religious freedom. In those days, there was legal discrimination in Britain against people who followed religions other than the “Established” church – the Church of England.

In the new colony of South Australia (once described as a “Paradise of Dissent”) all religions (or at least the various Christian denominations) were equal under the law and the followers of each denomination welcomed an opportunity to make their mark with prominent churches of their own.

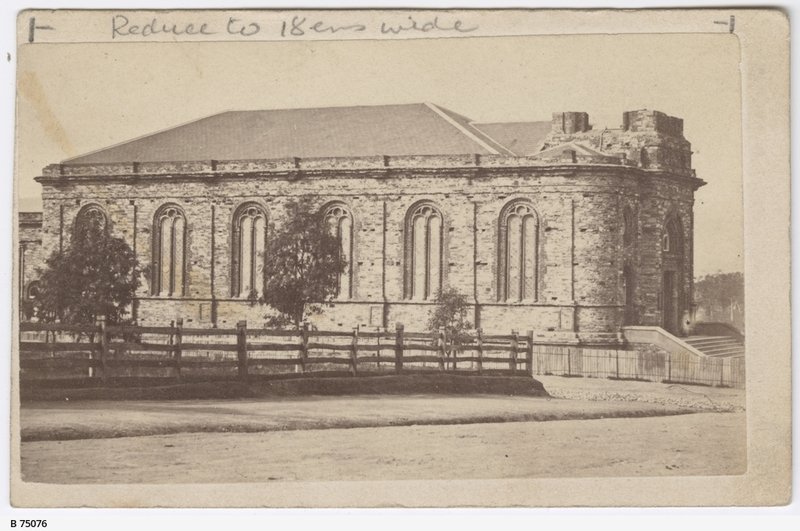

Brougham Place Congregational Church c1870 one year before the tower was added. Source: SLSA B-75076 ~ Creator: Edward Farndell

The first service was held in February, 1861. A tower was added in 1871 and a lecture hall in 1878 designed by architect Thomas Frost.

The pipe organ was built in 1881 at which time it was “the largest manual organ in the colony”

The organ was restored in 1914. The Church was often featured in postcards and photographs from the 1910s-to the 1930s. There is a lovely view of the church from the middle of Brougham Gardens - the vista is framed by the Adelaide Hills in the background.

The building is in some need of renovation and restoration, funding for which may be uncertain.

Rose Gardens

Opposite the church there is a bed of roses. Walking further north you will come across a number of other rose gardens dotted around the gardens.

The beautiful assortment of flowers (mostly on show in the warmer months of the year) is one of the main attractions of Brougham Gardens.

Each rose bed features masses of 80 to 100 rose bushes that are surrounded by lawn. The first roses were planted in the Gardens in 1905, with a bed of 24 bushes, but many more followed over the years.

A number of the rose beds are accompanied by commemorative plaques.

Now walk northwards, along the path. Stop next to two tall Italian cypress trees and a single cast iron bollard.

6. The trees of Brougham Gardens

Brougham Gardens contains a very wide array of trees. Many of the exotic species were donated to the gardens by wealthy North Adelaide residents in the 1890’s.

To get to this point, you have just walked past a large carob tree which dates from the 1860s or 70s. Opposite the carob tree was a Turpentine tree from the Middle East.

These two Italian Cypress trees form a frame to the entry pathway.

Nearby there are several California fan palms. These were donated in the 1890s by the then Chief Justice and Lieutenant-Governor Sir Samuel Way. This trail will later go past Sir Samuel’s former home, in Palmer Place.

On the northern edge of Brougham Gardens, you can see a line of Jacaranda trees, that are spectacular when in bloom during November

Further along, to the west, opposite a block of apartments is an unusual Chilean Wine Palm with a fat trunk. It was probably planted in the 1890’s.

The gardens also contain many other palm trees, Manchurian Pear trees, English elm and Dutch elm trees, and isolated one-off examples of trees such as a Duranta, a Japanese Pagoda, a Red Mulberry, a Fiddlewood, a Cotoneaster, a Queensland Brush Box, a Photinia, a “Weeping Fig”, a Coral tree, and two Lilly Pilly trees.

Most of the pathways are lined with one species of tree along the length of the pathway.

• The pathway that runs east-west through the centre of the Gardens is lined with English elm trees.

• Two paths near the Womens and Childrens Hospital are lined with a dozen Hackberry trees.

• The southern edge of the gardens, opposite the hospital is lined with London Plane trees.

• The diagonal path from the south-east corner to the centre of the gardens is lined with a dozen Iowa crab apple trees

• The path that follows the route of the old Bagot Road towards Lefevre Tce is lined with white cedar trees

From this point, walk westwards towards O’Connell Street and stop opposite a building with a fish-scaled, tiled tower or spire.

7. Lincoln College

Here, on the northern side of Brougham Gardens is a collection of eight buildings that together are known as “Lincoln College”. Four of them have frontages on Brougham Place (all State Heritage-listed) and the other four buildings are located behind, off Ward Street.

This is a residential college for tertiary students, operated by the Uniting Church and is available for students at any of Adelaide’s universities, although it is affiliated with Adelaide University. It was founded in 1952 by what was then the Methodist Church. It’s named after Lincoln College at Oxford in the UK.

Originally it was only for young men. Since 1973, women have also been allowed to stay here. It has professional staff: a chief executive, a Dean, an academic tutor and a building services manager. On the right is the East lawn.

To the left of the East Lawn is ‘Federation house” (number 32 Brougham Place). This is the former residence of Sir Richard Chaffey Baker who was a barrister, pastoralist and politician.

Sir Richard was the first South Australian born member of the Legislative Council, and later a Senator and the first President of the Australian Senate. He was knighted in 1895 and appointed Queen’s Counsel in 1900. Mr Baker is regarded as one of the founding fathers of federation and was a member of the Federal Conventions of 1891 and 1897-98. It remains a Heritage Listed Building of South Australia, of extreme historical value. In 2009 Federation House was re-opened following extensive renovations. It houses 12 student rooms; a common area; a kitchen and dining room as well as two function rooms. It’s also the residence of the Lincoln College Dean.

To the left of Federation House is Abraham House. It used to be known just as the “Annexe” because it’s connected to the Federation building. It was named to posthumously honour Dr Samuel Abraham who went on from being a resident here in the 1950’s to becoming a paediatrician both overseas and in Australia. Dr Abraham championed philanthropic projects in Malaysia. Abraham House hosts 20 student rooms with reading rooms, kitchen and common areas.

Third from the right, Number 39 Brougham Place (also known as Whitehead) built in 1907 was the home of a former Adelaide Lord Mayor, Sir Arthur Rymill (after whom Rymill Park was named). His father also lived here in the very early 1900’s. This grand villa of sandstone with a fish scale tiled tower is typical of the grand residences of the Edwardian period. The Whitehead building is the residence of the Lincoln College CEO.

The final building, on the left is Milne House – the administration building for Lincoln College. This is number 45 Brougham Place.

This grand residence was built in the late 1880s for wine and spirit merchant George Milne. Federation style houses are relatively rare in South Australia because, in the short period when they were popular, South Australia was less prosperous than neighbouring States.

Federation-style houses in SA were different from those in the rest in Australia in having walls of stone instead of brick and strongly coloured paint rather than white paint on their woodwork.

This was the first building to be bought by the then Methodist Church in 1951 for :Lincoln College. At the time, it cost 25-thousand pounds.

The building has undergone a significant restoration to its external woodwork. Heritage architect Bill Kay designed a new veranda that is as close as possible to the original.

The veranda was officially re-opened during Lincoln College’s Homecoming Weekend in April 2012 as part of the College's Diamond Jubilee Celebrations.

From this point, walk westwards towards the traffic lights. Cross over King William Road to join the western portion of Brougham Gardens.

8. Western corner

Crossing over King William Road you will reach the smaller western section of Brougham Gardens, which is triangular in shape. This area provides a view over the skyline of Adelaide, including the spires of St Peter’s Cathedral.

Lining King William road, on this south-western side, are more than a dozen London Plane trees. Behind them are many crepe myrtle trees.

In the rest of this section, if you come at the right time of the year, you can be greeted by a riot of colour.

The pathway that heads south-west down the hill is lined with a dozen “Royal Raindrops” pink-flowering crab apple trees.

You can also see hibiscus trees here, lilly pilly trees and along the northern edge, several jacarandas,

On the southern edge of this section of the Gardens, you will find three Victorian era cast-iron bollards that are painted silver. They were probably relocated here in the 1920s by City Gardener August Pelzer.

Also in the western corner of Brougham Gardens, you will see a towering Date Palm behind two English Elms. The Date Palm probably originates from a number of specimens that were donated in the 1890’s by Sir Samuel Way.

From this point, keep walking westwards, and cross from Brougham Place into Palmer Place, and into the northern tip of Palmer Gardens.

Part 2: Palmer Gardens / Pangki Pangki

9.

Naming and History

Palmer Gardens is also known as Pangki Pangki or Park 28. It’s named after South Australian Colonisation Commissioner Colonel George Palmer, who was born in 1799 and who died in 1883.

The Mid-Murray town of Palmer, just east of the Adelaide Hills region, is also named after the Colonel.

Pangki Pangki was a Kaurna tracker and guide. Pangki Pangki accompanied early officials Moorhouse and Tollmer up the Murray River to Lake Bonney and the Rufus River.

Palmer Gardens historically has been managed and planted in close parallel with Brougham Gardens – both gardens in the style of the Victorian era, although many of the trees were planted during the first decades of the 20th century, just after the time of Queen Victoria.

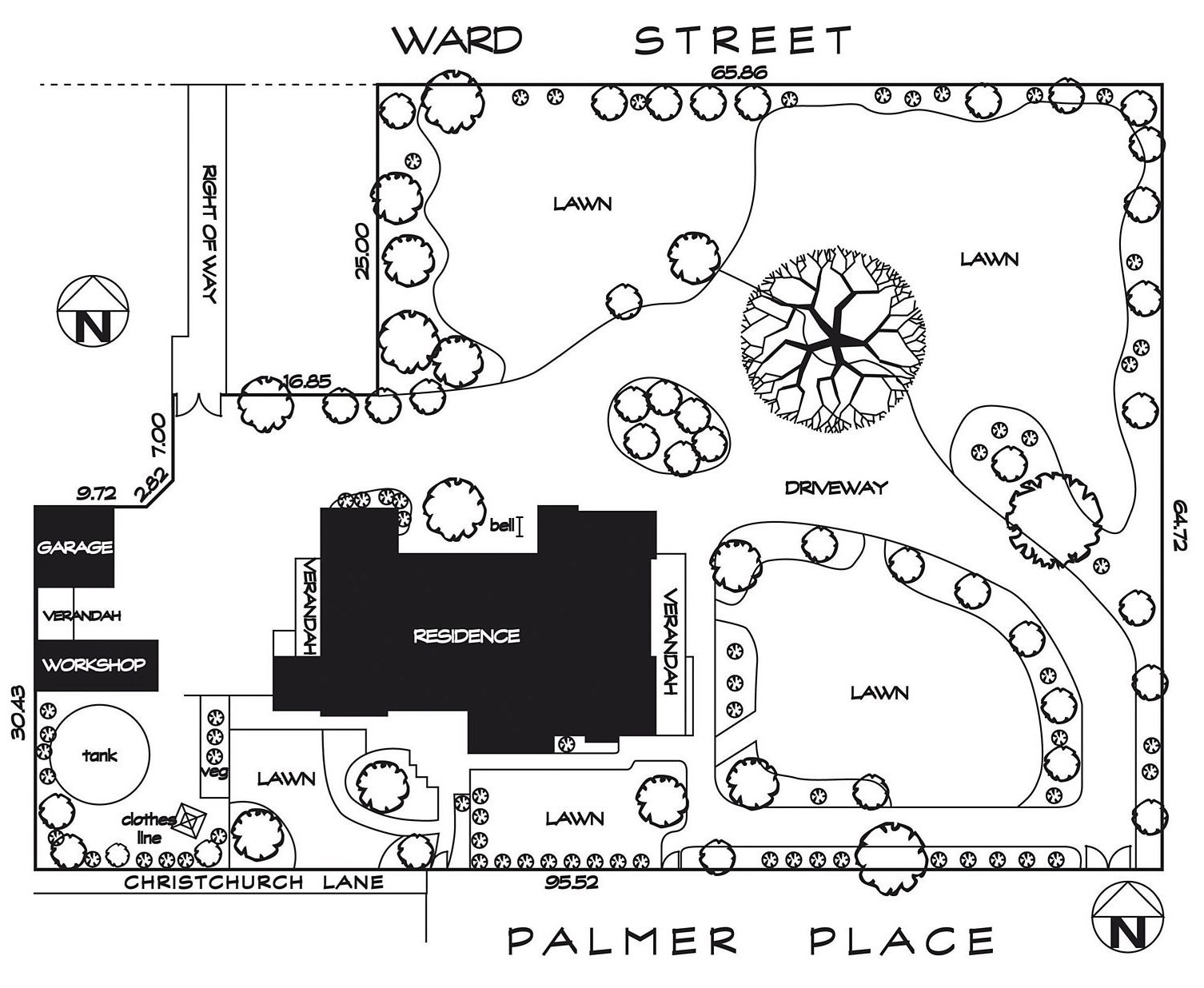

The road that surrounds Palmer Gardens on all three sides is named Palmer Place.

The layout and area of Palmer Gardens – a triangle of one-point-eight hectares is exactly as it was devised in 1837 by Colonel William Light. It is the smallest park in the Adelaide Park Lands.

The dominant feature is the two diagonal crossing pathways. They have existed since the 1860’s.

In the first decades of European settlement Palmer Gardens suffered a fate similar to that of the rest of the Adelaide Park Lands. The trees were felled for firewood and building. The Park was used for grazing stock. Tree plantings commenced in the 1870s when it began to be altered into a semi-formal garden, and this is how it remains.

From this entry point, walk along the path – past jacaranda trees on both sides of the path, until you reach a central path intersection.

There, turn left to find a park bench with a curious plaque attached.

10. Vedalia Beetle Seat

The brass plaque on this Victorian era style bench seat is in memory of the discovery of the ladybird Vedalia Beetle in the Gardens by German entomologist Albert Koebele in October 1888.

Albert Koebele ~ Source: https://faculty.ucr.edu/

Creator: unknown ~ Date: c1880s

Mr Koebele was the world’s first “economic entomologist”. That is to say, he was the first person to successfully use insects to control pests. He travelled the world looking for insects that could be imported to other countries to control pests that were damaging crops.

His big breakthrough occurred in this Garden in 1888. The Australian ladybird “Vedalia Beetle” that he found here, was responsible for saving the citrus industry in California.

The beetles were exported from here back to the US and successfully controlled the “cottony cushion scale” insect that had been threatening to wipe out the entire citrus industry there.

Mr Koebele had other successes but none as dramatic as that one, which is internationally recognised as the starting point of modern biological control of insects.

The plaque and seat were sponsored by the Australian Entomological Society on the occasion of their annual general meeting in Adelaide in 1994, and unveiled by the then Lord Mayor Henry Ninio.

Vedalia Beetle (Rodolia cardinalis) adults attacking cottony cushion scale. Photo: JK Clark, University of California Statewide IPM Project, 2000.

From here, keeping walking south-east, back towards the roadway. You will pass Magnolia trees on both sides of the path.

11. The Trees of Palmer Gardens

.

Each edge of the Palmer Gardens triangle features a different species of tree.

Here on the eastern side, the garden is lined with what botanists call “Quercus palustris” – commonly known as Pin Oak or Swamp Spanish Oak.

On the northern edge is a row of jacaranda trees – which bloom every November.

On the western edge are several Ginkgo trees - “Ginkgo biloba” also known as a Maidenhair tree. It is a deciduous tree native to China, Korea and Japan. Ginkgo leaves and seeds have a long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine for a range of conditions. Ginkgo is one of the most widely used herbal medicines. There are more than 400 products that contain Ginkgo on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). The Therapeutic Goods Administration says these listed medicines and are commonly indicated for stimulating blood circulation.

Other notable trees include:

north of the Ginkgo along the western edge, three Chinese Pistachio trees;

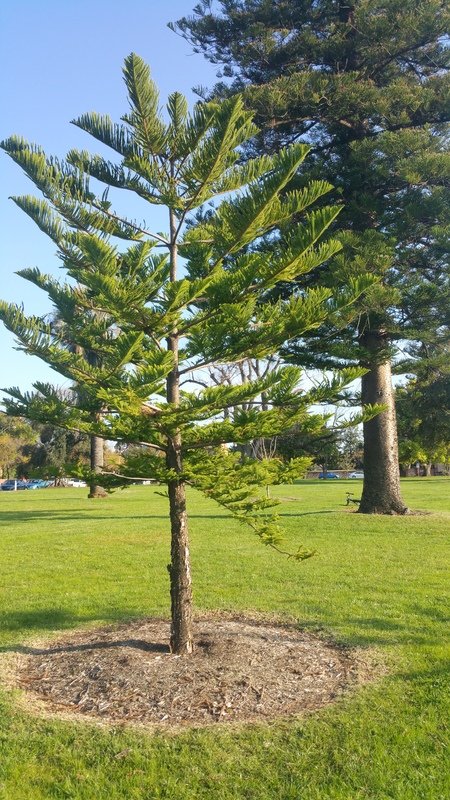

in the centre of the gardens, four Norfolk Island Pine trees;

in the southern central section, four Golden Himalayan cedars;

nearby there are also two Weeping Golden Cypress trees;

two very old European Olives (on the western side);

several Norfolk Island Hibiscus trees (near the centre); and

a very large camphor laurel tree in the northern part of the gardens.

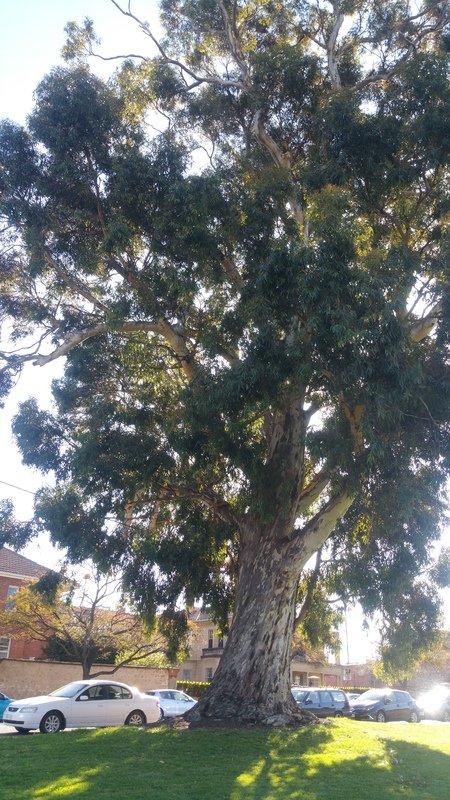

However the most dominant tree in the Gardens, by far, is the towering gum tree near the southern corner. This is a Sugar Gum and probably dates from the 1880s if not earlier.

At the southern tip of Palmer Gardens are two Date Palms. If you walked to that point you would get a good view of Colonel Light’s statue, across Pennington Terrace in Park 26.

You would also have tree-filtered views of the city skyline and the Adelaide Oval complex.

But this trail now continues only a little further south along the eastern side of Palmer Place, past Kermode Street.

Walk until you reach number 95 Palmer Place.

That’s where you’ll start to learn about some of the historic buildings that surround these Gardens.

12. Doolette House & Kindergarten Union

95 Palmer Place

This house (number 95) was built in 1883 for one of SA’s early businessmen, George Philip Doolette.

Mr Doolette arrived in South Australia in 1855 at the age of 15, with his parents, from Ireland. As a teenager, he found work at a drapery in King William Street. 20 years later, at the age of 35, he was the sole proprietor of the business trading as “George P. Doolette, Court and Clerical Tailors”.

George P Doolette (1840-1924) ~ Creator: unknown ~ Date: (1840-1924)

In common with many other successful merchants he then invested in pastoral properties and mining ventures, as well as building this “elaborate villa” in 1883.

Mr Doolette was also a prominent member of the North Adelaide Congregational church (what’s now the Brougham Place Uniting Church you saw earlier on this trail) and he was vice president of the “Young Women’s Christian Association.”

George Doolette lived here for about thirteen years until 1896 before moving to England. There, he capped a career of lucrative financial ventures by floating several major mining companies in Western Australia, including Great Boulder (at Kalgoorlie) a very successful gold mining operation. In later life, he became chairman of the Western Australian Mine Owners’ Association.

Doolette was knighted in 1916. He died in England in 1924 but his ashes were returned to Adelaide.

In the 20th century this building became a training college for kindergarten teachers, and the headquarters of the Kindergarten Union of SA.

The Kindergarten Union was started in 1905 by several socially-conscious upper and middle-class men and women associated with Adelaide University (names like Barr-Smith, Waite, and Mitchell). They wanted to care for and help educate children aged between three and six, especially in Adelaide’s poorer districts. The first kindergarten was set up in 1906 in Franklin Street in the city which was, at the time, one of the poorer working-class parts of the city.

This building itself was not a kindergarten. The driving forces behind the Kindergarten Union were the Reverend Bertram Hawker, and Catherine Helen Spence. Private donations from the public allowed the Kindergarten Union to provide free kindergartens for decades. It wasn’t until 1975 that its role was recognised in law, and then in 1985, the State Government took it over, after which this building could be used once again as a private residence.

From here, walk across the Park to the giant sugar gum tree.

13. Montefiore (Part of Aquinas College)

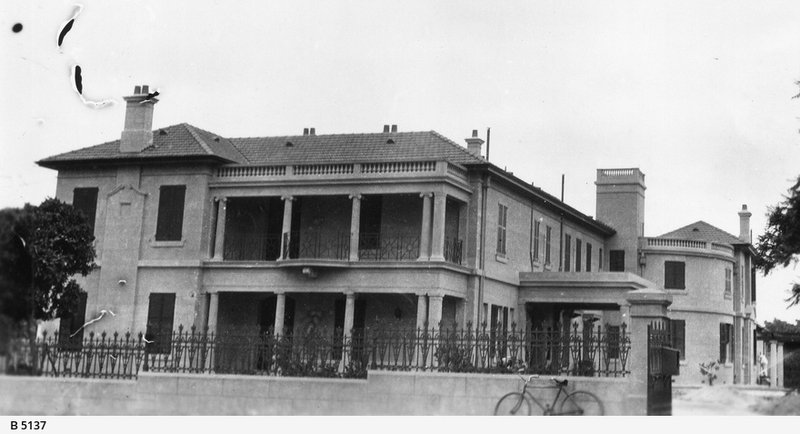

There are two buildings opposite the sugar gum tree, but we are concerned not with the red brick one, but the one on the right, known as “Montefiore”. Although it’s much altered from its original state, it’s still rich in historical association.

It had two early owners in the 1850’s and 1860’s: a civil engineer, surveyor and architect named George Green and then a solicitor named Luke Michael Cullen. However this building became famous from the 1870’s onwards because it was the home of Sir Samuel Way, one of South Australia’s most famous men.

Samuel Way was a baronet, and chief justice from 1876 until his death in 1916. He was also chancellor of the University, first grand master of the United Grand Lodge of Freemasons in South Australia, and a notable philanthropist.

During the late 1870s Sir Samuel Way refaced and extended the building in Italianate form.

"Montefiore" in 1928 - just before major renovations (L) and in 1929, after renovations (R) ~ Source: State Library of South Australia B-4889 ~ Date: 1928/ 1929

Way’s vast alterations included an impressive sweep of marble steps which has survived all subsequent alterations. The house was pre-eminently a reflection of Way’s status, interest and tastes.

In the book “A Social History of North Adelaide 1837-1901” Paula Nagel queries Way’s aesthetic tastes but notes that he “certainly had a home and garden not to be equalled by any other in North Adelaide. He entertained a great deal, in administrative, academic, dramatical and musical circles. ‘Montefiore’ of the 1870’s and 1880’s developed a reputation as the ‘Centre of the Arts’.”

After Way’s death the size of Montefiore was considerably reduced, and the house reached its present form. Since 1948 the house has been a major component of Aquinas College, one of the residential colleges of the University of Adelaide.

Now, walk a little further north to look at the house next door.

14. Roche House

21 Palmer Place

This house has a connection with the famous Ayers family. You’ve heard of Ayers Rock? We now call it Uluru but it was named in English after Sir Henry Ayers who was five times Premier of South Australia. This house was built in 1905 by Sir Henry’s son, Arthur Ernest Ayers.

After Arthur Ayers’ death the house passed in the 1920s to Sir Collier Cudmore, solicitor; president of the Liberal and Country League in the 1930’s. He was also an Olympic gold medallist in 1908, as a rower – rowing for Britain where he was studying at the time.

Roche House, 21-25 Palmer Place in 1953. Source: State Library of South Australia B-12830 ~ Date: 1953

The house was purchased by Aquinas College in 1953; effectively extending the college from the historic Montefiore building to its left.

Such a purchase by an institution reflected social changes after the Second World War, such as the steep decline in the numbers of women working as domestic servants, and the difficulties of continuing to maintain grand city residences.

The building is an excellent example of a large federation house in which emphasis was placed on assymetry, variety of roof form (tiles, gables and projections were common) and notable detailing to the brickwork – especially the porch and adjacent window, and the quality of the joinery inside.

Heritage experts have noted that there are unsympathetic additions at the rear of the building but these are not obtrusive. Its use as a residential college is compatible with the original function but has required some internal alterations.

The house is a highly significant part of the streetscape because of its scale and its landscaped surroundings.

Now, walk a little further north to look at the house next door.

15. Boyd House

27 Palmer Place

This building at number 27 is the only structure designed in South Australia by the internationally renown architect Robin Boyd.

Boyd was famous from the 1950’s onwards, as an advocate of a new style of architecture, functionally suited to Australian climate and lifestyle. He wrote several widely-read books on the subject. He studied in England, Europe and the US in the 1950’s and was on Canberra’s National Capital Planning Committee Canberra in 1967.

He received the royal honour of CBE (Commander of the British Empire) in 1971.

While on a lecture visit to Adelaide in the early 1950s Robin Boyd stayed with the architect Gavin Walkley in a stone house on this site that had been built in the 1840’s. The original house was suffering from old age ,and requiring a lot of expensive maintenance so Walkley decided to demolish it.

Walkley asked Boyd to design a house which would take into consideration the magnificent view of the Adelaide hills.

In 1955 when it was designed, and in 1956 when it was built, there were many aspects of the design, including the steel frame, that were very new, especially to South Australia. The builder had some difficulty with the unfamiliar construction of the time, and most of the neighbours disapproved of the design.

The house is a significant example of the `International Style’ which emerged in the USA in the late 1940’s. The mushroom-shaped form of the house enhances the way the upper floor appears to float above the ground.

While the building has nothing in common with its neighbours, its integrity is high, it is of small scale and unobtrusive.

Now cast your eyes over to the two-storey stone house next door, on the right, at 29 Palmer Place. That house originally had a ground floor veranda with interesting wooden fretwork over the front entrance. In 1927 the stone walls were rendered and a double storey veranda with large pillars was added.

Now walk a few metres further north to the Anglican Church “Rectory” at number 35.

16. Christ Church and Rectory

35-39 Palmer Place

Christ Church and the flanking residences known as Bishop’s Court (on the right of the Church) and the Rectory (to the left of the Church) form perhaps the best known and most revered group of heritage items in Adelaide.

These buildings are much older than the grand St Peters Cathedral, off Pennington Terrace, which is the centre of the Anglican diocese of Adelaide.

The integrity of the group remains high and its significance to South Australia and the City of Adelaide in particular is beyond doubt as the foremost representation of the development and consolidation of the Anglican Church in South Australia. As a whole the group is unique in extent, age, and as a record of working church buildings of the late 1840s and early 1850s.

Before we talk about the buildings, we need to say a few words about the man who more than any other was responsible for their construction.

Bishop Augustus Short (1802-1883) ~ Creator: unknown

Augustus Short, was born in 1802 and lived to the age of 81, dying in 1883. This was his territory.

The son of a barrister, he was educated at Westminster and Christ Church at Oxford in the 1820's before being ordained as a priest.

In 1845 he got the opportunity for a promotion to bishop, if he would go to the colonies. He was given the choice of either Adelaide or Newcastle. He chose Adelaide and arrived in 1847.

His vast diocese included Western Australia. At the commencement he had only eight clergy and four church buildings.

As mentioned earlier on this trail, South Australia was founded as a colony to allow or encourage “dissenters” or “non-conformists” - people not necessarily enamoured of the Anglican Church. Bishop Short was, in contrast, a man of the establishment – a “high” church man and frequently clashed sometimes with his own Anglican flock and with others in the colony – on matters of Church doctrine.

Bishop Short lived in Adelaide here in Palmer Place for 34 years. He went back to England in 1882 where he died the next year.

Bishop Short brought plans for the buildings from England, although reports at the time of their construction credit their design to local architects Henry Stuckey and William Weir.

The church is constructed of Adelaide limestone. The stone was quarried within the Adelaide Park Lands – in fact right behind Government House near what’s now the Torrens Parade grounds.

The foundation stone of Christ Church was laid in 1848, and it was consecrated 18 months later, in December 1849, but it took another 23 years until it was completed.

The nave (i.e. the aisle for the congregation) came in 1855 – designed by Edmund Wright. The apse (ie the semicircular recess covered with a dome) came another five years later again in 1860.

This church’s apse contains a combination of limestone rubble walling and sandstone dressings with brick quoins. It was finally completed in 1872 with a new boarded ceiling, porches and a turret at the crossing for ventilation.

Bishop Short used this Church as a de facto cathedral while trying to raise funds for the later construction of St Peters Cathedral.

In the 1850’s he contributed 1,000 pounds for the completion of this Church.

It’s one of the focal elements of Palmer Gardens and Palmer Place but because it’s tucked out of the way, it’s not nearly as well known in Adelaide as the much more obvious St Peters Cathedral.

There are three Victorian-era cast-iron bollards, now silver-painted, at the Christ Church end of the Gardens pathway. The bollards have been there since 1922.

Now turn the corner and view the mansion next door on your right.

17. Bishop’s Court & stables

For many decades this historic corner was unfortunately part-shielded from view by a green coloured metal gardener’s shed on the gardens. A shed had occupied a prominent site there for decades. In January 2019. the Adelaide Park Lands Association brought attention to how ugly it was. We queried why it was necessary at all, and it was promptly removed!

In January 1851 Bishop Augustus Short’s son laid the foundation stone for this building that would become his father’s Episcopal residence, Bishop’s Court.

At the time, the South Australian Register newspaper described the proposed building as “a chaste design in the Tudor Gothic, but by no means an ambitious structure for an episcopal palace.”

The architect, Mr Stuckey, died less than six months later, so fellow architect Edmund Wright probably supervised most of the construction.

Erection of the building was slow because of the exodus of labour at that time, to the Victorian gold fields. For a time the walls of the original central section of the building remained without a roof until Bishop Short raised a loan to cover the cost of roofing.

Bishop’s Court 1954. Photo: State Library of SA B 13043

Part of the building was consecrated in 1852, but extensions were added over several decades, up to 1912 when a chapel and entrance porch were added to the north face.

The book: Heritage of the City of Adelaide, says: “Bishops Court ….is remarkable for the assemblage of various extensions under differing roofs to form a homogeneous architectural composition.”

In 2020 the Anglican Church offered Bishop’s Court for sale. It was purchased in September 2020 for a price that broke the previous Adelaide house price record of $7 million. The new owner was businesswoman Mary Kotses – the founder and owner of homewares and lifestyle stores Wheel & Barrow and Karma Living. Mrs Kotses said that she intended to use it as a family home and plans to renovate it, over time.

Now walk a few steps to the east, to view the house next door, on your right.

18. Honeywill House

51-54 Palmer Place

A drapery merchant, William Honeywill had this house built in 1901. He was a partner in the Rundle Street business of Charles Birks & Co.

Only a few years afterwards life in this grand new house was struck by tragedy when Honeywill’s wife, Emily. committed suicide here in their home, in December 1908. Honeywill then sold the property in 1910. Keeping a grand house for only nine years was unusual in that era.

The next purchaser, Frederick William Bullock, who owned the house for twenty-two years, was senior partner in the firm founded by his father F. W. Bullock and Co., auctioneers, land and estate agents.

Frederick Bullock was also a councillor, alderman and mayor of the Adelaide City Council and, in common with many businessmen and public figures, was “...a very distinguished member of the Masonic fraternity.”

The book: Heritage of the City of Adelaide, says “The house ...is an Edwardian variant of the traditional Victorian asymmetrical bay-windowed villa with lofty proportions and quality masonry, brickwork and joinery. The Art Nouveau-influenced joinery to the veranda frieze work and balustrading is of particular interest.’

In recent decades, the building was occupied by the College of Surgeons, but in 2022 once again became a private dwelling.

Now walk a few steps to the east, to view the house next door, on your right.

19. House and stables

‘Duncraig’

58 Palmer Place

This house, known as “Duncraig” , was built for Walter Hughes Duncan, a highly successful South Australian pastoralist and mine owner.

Mr Duncan owned a property near Saddleworth and leased Oulnina Station, a property of some two thousand square kilometres, up until his death. He was chairman of what was then called the Waterloo District Council (now part of the Clare and Gilbert Valleys Council area).

Walter Duncan was also a State politician (a member of the House of Assembly). He was a conservative – a member of a party called the ‘National Defence League”.

He was also lucky enough to be born into a family that owned a sheep station in the mid-north. On their sheep station copper was discovered in the 1860’;s and the family suddenly (and very successfully) went into the copper mining business

Mr Duncan was a major shareholder and director of Wallaroo and Moonta mines. With a fortune to his name from copper, he built this home between 1896 and 1902 while he was a member of Parliament.

Five years later he died on his way back to Australia from England, in May 1906. His widow, Alice, lived here until she died in 1928 and the house was bought by William Goodman.

Goodman is a famous Adelaide name. There is a “Goodman building” in the Botanic Gardens. The link with Mr Goodman is trams.

"Duncraig" - house at 58 Palmer Place ~2020

Sir William Goodman was an electrical engineer who designed tramway systems, first in Dunedin, New Zealand, and then here in Adelaide. He was the chief engineer AND general manager of the Municipal Tramways Trust from 1908 until 1950.

He was 42 years in that role, and ironically as he retired in his late 70’s the tramways were also retired in favour of buses. Mr Goodman was renowned as an energetic efficient and intelligent administrator. He was also the first chairman of another major statutory authority, the South Australian Housing Trust from 1937 to 1945. In those early years of the trust, the Board members, Goodman especially, carried out most of the administrative work themselves.

In Mr Goodman’s case this was usually done at night at his home here in Palmer Place.

This house “Duncraig” was completed in 1900. The stables (on Ward Street, behind the house) were built soon after the house and together with the front garden wall they form an integral complex.

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 1.5 Mb)

All of our Trail Guides and Guided Walks are on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people. The Adelaide Park Lands Association acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future traditional custodians and elders of these lands.