Take the Trail

Start at the “Conservatory Gate” off Plane Tree Drive (pictured below).

This Trail is on the traditional land of the Kaurna people.

Start at the Conservatory Gate. The Trail is about 2km. Allow 2 hours.

1. Introduction

2. “Cascade”

3. First Creek Wetlands

4. Oldest tree

5. Auracaria Avenue

6. Main lake

7. Palm House

8. Garden of Health

9. Gingko Gate

10. Economic Garden

11. Original flora

12. Moreton Bay fig tree avenue

13. Australian forest

14. Roses

15. Bicentennial conservatory - outside

16. Bicentennial conservatory - inside

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 5.1 Mb)

1. Introduction

Start here, at the “Conservatory Gate” on Plane Tree Drive, 150 metres west of Hackney Rd. (pictured).

Park 11 is a very large area – stretching from War Memorial Drive in the north, to North Terrace in the south, from Hackney Road in the east, to Frome Road in the west.

Within that big area, Park 11 includes the Royal Adelaide Zoo, the Adelaide Botanic Garden, Botanic Park, the small Frome Park, as well as the land that the State Government calls “Lot Fourteen” (that is, the site of the former Royal Adelaide Hospital) as well as the National Wine Centre, and the Botanic High School.

The various parts of Park 11. This Trail Guide covers only the area outlined in green, i.e. the Adelaide Botanic Garden.

This Trail Guide covers only the Adelaide Botanic Garden part of Park 11, outlined in green above. The route for the Trail Guide is about two and a half kilometres, and is likely to take about two hours. Walking instructions are designated by bold type in each of the stop descriptions.

There are public toilets within the Adelaide Botanic Garden and this Trail Guide goes past at least two of them.

Dogs are not permitted in the Botanic Garden. Bicycles may be wheeled through, but not ridden through the Garden.

Garden or Gardens? Singular or plural?

Although there are 11 different “garden” areas within the Adelaide Botanic Garden, it is officially singular, a “Garden” not “Gardens”. This is, in part, to distinguish it from the other Botanic Gardens in South Australia:

the Wittunga Botanic Garden at Blackwood, and

The Adelaide Botanic Garden has long been Adelaide’s most popular tourist attraction.

In November 2023, the Garden won a world accolade at the International Garden Tourism Awards, as “A Garden of the World Worth Traveling For.”

The Garden is open every day of the week, and is free to enter.

In the early days of the South Australian colony, there were four other sites that had been proposed or selected for the Adelaide Botanic Garden, before this site was adopted in 1854.

Under the stewardship of George Francis, it took three years of planning and planting - as well as his protection of some of the original flora - before the Garden was opened to the public in 1857. It was another 16 years before the related area of Park 11 behind you was to be established and planted out as an arboretum, called “Botanic Park”.

The Adelaide Botanic Garden is laid out over 51 hectares. As you can see from the map above, this Trail Guide does not include all the features in the Garden.

There are different, free guided tours of the Adelaide Botanic Garden available almost daily, departing from 10.30am from the Visitor Information Centre, located at the Schomburgk Pavilion in the centre of the Garden. (There’s also a free Adelaide Botanic Garden brochure available, with more information, including a map.) The volunteer guides change their walks monthly to show seasonal highlights and different plants.

Before entering the Garden, this is an opportunity to briefly mention one of the historical uses of this land in Park 11.

There was a “Lunatic Asylum” near the corner of Botanic Road and Hackney Road. It was built in 1852. Part of it was knocked down after 50 years – in 1902. Its purpose was later served by the much larger Glenside psychiatric hospital. Another part of the former “Lunatic Asylum” survived, as an infectious diseases hospital, until 1938.

A small “mortuary” for the Lunatic Asylum – built in 1883 - survives today within the Botanic Garden as a heritage item. You can see the old mortuary from Stop #6 on this Trail.

Although the Lunatic Asylum is long gone, a two-storey stone house that was built for its superintendent still exists on the corner of Botanic Road and Hackney Road. It’s called “Yarrabee House”, now the administrative headquarters of the National Wine Centre.

From here enter the Garden, and go south, along the left-hand side of the Bicentennial Conservatory (you’ll come back to it at the end of this Trail). Stop at a large glass sculpture.

2. “Cascade”

This sculpture, called “Cascade” was erected in the same year as the conservatory, 1988, and made of glass to complement the building design.

The artist was Sergio Redegalli from New South Wales. It was originally installed in Brisbane in 1988 at the World Expo to mark the Bicentenary of the First Fleet’s arrival in 1788, or what indigenous Australians call the “Invasion”. It was then relocated here, to complement the glass Bicentennial conservatory.

It has 500 precision-cut pieces of glass, each 6 millimetres thick, in the shape of a cascading wave. It weighs 12 tonnes.

From “Cascade” walk just a few paces to the east, and cross over a wide wooden bridge. Turn right, and follow the pathway past the “Little Sprouts Kitchen Garden”. Climb the concrete steps, to a lookout.

3. First Creek wetlands

At this point you are right on top of one of three ponds that together form the First Creek wetlands.

There are two separate creeks that run through the Botanic Garden. First Creek flows down the Adelaide Hills from Cleland Wildlife Park near Mt Lofty, through Burnside, under Hackney Road, and into the Botanic Garden here at the First Creek wetlands. First Creek then flows through Botanic Park, and under Frome Road, emptying into the River Torrens.

The other waterway is Botanic Creek, which runs through the eastern Park Lands, near East Terrace. It flows under or through the lake in Rymill Park, goes under Rundle Road and under North Terrace before emptying into a lake here in the Botanic Garden.

While standing on the lookout, look to the south-east to see this historic mortuary – the “dead house” of the former Lunatic Asylum.

The First Creek wetland ecosystem was constructed in 2013 as an integral part of a stormwater recycling system. It’s designed to eventually supply all of the Botanic Garden’s irrigation needs, thereby drought-proofing the entire Garden.

First Creek has been modified several times since the 1870s but it has always been a key feature of the Adelaide Botanic Garden. Prior to the creation of the wetland, the Creek would often overtop its banks, in this part of the Garden, three or four times per year. Now the wetland helps mitigate those floods.

Following rainfall, a proportion of the stormwater - 7.5% - is diverted from First Creek into the wetlands, where it’s treated through a series of purification processes. The creek water is naturally filtered and cleaned as it passes through the progression of ponds with their host of plants.

Several short-necked turtles (Emydura macquarii) can be spotted in the First Creek wetlands. Pic: Fran Mussared.

The diversion from First Creek into this wetland produces up to 100 megalitres of cleaned water which is then stored in an underlying aquifer to be subsequently drawn on to water the Garden.

There are an estimated 20,000 plants here in the First Creek wetlands, many of which are Australian natives. Some are rare and endangered South Australian plants, which have been grown from seeds collected by the Seed Conservation Centre - also located here in the Botanic Garden (in the nearby Goodman Building). Incidentally, around half the plant species in this state and nearly 85% of SA’s threatened species are currently stored in the Seed Bank and form part of this Garden’s living collections.

What’s been created here is the kind of wetland that once would have naturally occurred here and around our other creeks and rivers. Apart from providing a sustainable source of clean water for the Garden, the First Creek wetland also plays an important educational role, giving us the opportunity to become more familiar with the variety of wetland plants and the valuable functions they perform.

Now, retrace your steps, and go back over the bridge. Turn left at the ‘Cascade’ sculpture, to see (on the western, or right-hand side of the path) a large ancient tree lying on the ground.

4. Oldest tree

Pic: Botanic Gardens SA

These are the ancient remains of one of Australia’s most revered trees, the River Red Gum. While it may no longer be alive, it is without doubt the oldest tree, by far, to be found in the Adelaide Botanic Garden.

This ghost from a past forest lies here, almost invisible to passersby. Astonishingly, it’s thought to have lived between 1,500 to 2,000 years ago and had reached around 500 years old when it died.

Scientists at the State Herbarium think the structure of the tree rings can tell us about the local climate in the area when the tree was alive.

It was recovered by Forestry SA from Mount Crawford and was probably part of an ancient Red Gum forest in the area.

The log weighs an estimated 15 tonnes and is 13 metres long.

It’s hard for us to imagine a present day link - like this - to our own ancestors from two thousand years ago! So it’s quite a privilege for us to be in the presence of such an ancient local tree.

From here, walk south on the pathway until you reach a toadstool sculpture in the lawns to your right. Enter the lawns at this point to walk south west, up the rise, to reach an avenue of tall trees.

5. Araucaria Avenue

This avenue of trees was planted early in the life of the Adelaide Botanic Garden, in 1868, under the directorship of Dr Richard Schomburg, after whom the nearby Schomburg Pavillion down the slope here, is named.

The genus of trees with the scientific name “Araucaria” evolved as far back as the Jurassic period (about 201 to 145 million years ago) when vast forests of these trees provided food for long-necked Sauropod dinosaurs.

This avenue of trees is considered of State significance and exceptional cultural value. There was previously a bitumen pathway running through this avenue. Removal of the bitumen, some years ago, seems to have delivered a hoped-for boost to the trees’ health.

The genus, Araucaria includes the well-known Norfolk Island pone, but also the Bunya Pine, Hoop Pine, the Monkey Puzzle from Chilé and the New Caledonia Pine.

There are four specimens of New Caledonia Pine in this Avenue - all planted in 1868. The tree has a tall, narrow canopy and can attain a height of 30 metres or more. It is often misidentified as Norfolk Island Pine. However, it differs in being column-like, narrowing to a point on the top, with a tendency for the tree trunk to bend, or the whole tree to lean.

Pic: @adelaidewriter

The other 12 trees in the planting are indeed Norfolk Island Pines and they provide an excellent opportunity to observe the differences between the two species.

There are also several specimens of Bunya Pine in the Botanic Garden. You will see one later on this Trail in the Australian Forest.

Now walk south-west downhill through the Avenue to reach the Main Lake. Turn left to reach a good viewing position on the lawns facing the southern bank.

6. Main lake

Pic: @Bottlo74

It’s hard to visualise how different the site of the Adelaide Botanic Garden must have looked just a couple of hundred years ago, before Europeans arrived and changed the landscape.

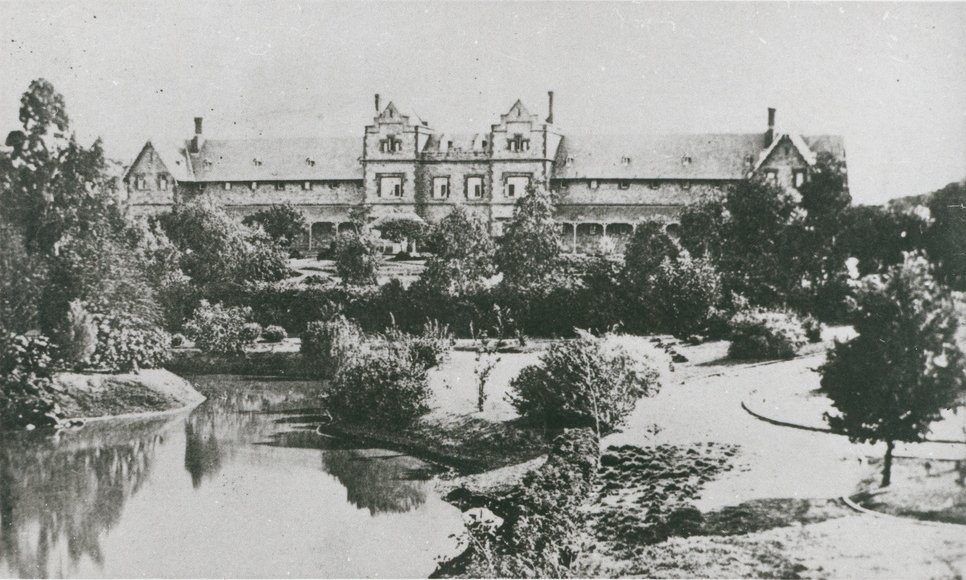

The main lake in 1908. Pic: State Library of SA (B 17284). The image was edited and colourised by Kelly Bonato at A Colourful History.

However, we know that well before European colonisation, this main lake was a waterhole, important to the region’s Kaurna people. The waterhole was fed by an ephemeral creek, that we now call Botanic Creek. The former waterhole was landscaped and enlarged to become a feature of the Garden.

The land now occupied by the Botanic Garden and Botanic Park was previously the site of large Aboriginal camps, in the period from 1845 to the 1870s.

Kaurna tribal leader, Ityamai-itpina - named King Rodney by Europeans - was a significant contributor in colonial times to what we now call ‘reconciliation.”

His daughter, Iparrityi (sometimes spelled Ivaritji) became an elder in the 1930s, when she passed on valuable information about Kaurna history. She said her father had a special affinity with the waterhole. She said it was named Kainka Wirra, meaning ‘eucalyptus forest’.

Now, walk westwards around the lake, turning left onto the adjacent lawn to stand in front of the historic 1877 Palm House.

7. Palm House

This elegant glasshouse is one of the treasures of the Adelaide Botanic Garden.

The Palm House is an exquisite, painstakingly restored Victorian glasshouse imported in pieces from Bremen, Germany in 1875, and assembled here.

It is thought to be the only one of its kind still in existence anywhere in the world.

The Palm House was designed by German architect Gustav Runge.

The sophisticated engineering techniques used in its construction make it a benchmark in glasshouse design.

The hanging glass walls are similar to those used in today's city buildings and were very advanced for the time.

This sophistication, and Adelaide's dry climate, probably account for the building's survival.

In 1986, corrosion of iron glazing bars made the Palm House unsafe for public use and it was closed to the public. There were fears in the late 1980s that it might never be re-opened.

A conservation study carried out in early 1991 recommended full restoration. After a successful public appeal, and a contribution from the Federal government, the restoration was completed in 1995, allowing the Palm House to re-open after being closed for the previous nine years.

Later, in 2018, further works were required to treat salt damp and corrosion, and to prune plants to allow light to reach smaller plants. After a second closure (this time just eight months) the heritage-listed building was opened again for all to enjoy.

Since the mid-1990s, after the first restoration, it has housed a collection of plants from Madagascar. The plants require warm and dry growing conditions, which also aids in the conservation of the building. Many of the Madagascan plants are under threat in their home environment.

Behind the palm house is this Pony Tail Palm (Beaucarnea recurvata) native to Mexico. It would have been planted about 1920.

Inside the Palm House, the grotto at the western end, with its delicate maidenhair fern, was built from fossil-bearing limestone from Germany.

Now, exit the Palm House from the front (northern) door, and walk to the northern section of the Garden of Health, signposted as ‘The Garden of Contemplation.’

8. Garden of Health

The Garden of Health demonstrates the use of plants to heal and promote health and wellbeing in western and non-western cultures. Spending time here, you can get a sense of how this use has developed over the course of human history.

There are over 2,300 plants from 257 species in this Garden of Health.

The Garden of Health is divided into two sections; the northern side, the Garden of Contemplation, focuses on wellbeing and encourages contemplation and reflection, while the southern side, the Garden of Healing, is about disease prevention and the treatment of illness.

So these two adjoining Gardens are dedicated to both mental and physical health.

The Garden of Healing conceptualises the use of medicinal plants from eastern and western cultures. Species from Middle East and Northern African regions, China, India, Indigenous Australia and North and South America have been gathered to form a collection rich in diversity that specialises in healing properties.

The Garden of Healing demonstrates the historical contributions of plants for over 60,000 years, as well as the importance of plants in pharmaceutical discovery and modern medicine.

Now, walk toward the tall ornate gate on the western boundary of the Botanic Garden.

9. Gingko Gate

Pic: John Zwar

On the western edge of the Garden of Health there is a tall metal gate that marks the boundary of the Botanic Garden.

This “Gingko Gate” was installed in 2010. It’s made of bronze and steel; designed by Adelaide artistic couple: the late Hossein Valamanesh and his wife Angela Valamanesh. Angela was one of the judges in the 2023 Adelaide Park Lands Art Prize.

The fan or butterfly-shaped motif adorning the Gate is the leaf of the Gingko Biloba tree. There is a living specimen of this tree growing here near the Gate.

The leaves of the Gingko tree have been used for centuries in traditional medicine. Flavonoids extracted from Gingko leaves are used in pharmaceutical supplements as antioxidants and to improve blood flow.

The Gingko tree arose from the fern kingdom and is considered to be the world’s oldest living species of tree.

Geological evidence of ginkgo’s have been dated to the Mesozoic era, some 200 million years ago. Unlike other tree leaves, its double-lobed leaves bear no central vein, a feature it’s retained from its fern ancestry.

Pictured in autumn: a gingko biloba tree growing near the Gingko Gate. Photo: Kate Elmes.

Pictured from outside the Botanic Garden, looking back to the east, the ‘Gingko Gate’ . Pic: https://www.experienceadelaide.com.au/

Now, walk straight ahead in an easterly direction to enter the Economic Garden. Stop at the central fountain.

10. Economic Garden

Pic: Botanic Gardens of SA

The fountain in the centre of the Economic Garden has been listed as a State Heritage place since 1986.

The “Boy and Serpent Fountain” is one of only two known surviving examples of this work by the Coalbrookdale foundry in England.

It was donated to the Botanic Garden in 1908, by one of Adelaide’s most prominent philanthropists, Robert Barr Smith.

Its State Heritage listing says that: “Aesthetically and technically, the Boy and Serpent Fountain, illustrates the technical possibilities of late 19th century English cast iron manufacturing processes – including mass production and prefabrication.”

The fountain was removed during winter 2018, for three months of restoration work, after showing signs of corrosion and coatings failure.

This Economic Garden is dedicated to plants that have been regarded as having ‘economic value’, such as plants for eating or weaving.

Rainbow lorikeets enjoying the “Boy and Serpent” fountain in the Economic Garden. Pic: Shane Sody

A wander amongst the beds will reveal how certain fibres, oils, herbs and spices look in their living plant form, before they are harvested and processed into the products we know and use.

One of the species in the Economic Garden, Coreopsis grandifloria, a perennial herb. Pic: @BotGardenssa

You might even see some of the Botanic Garden restaurant staff foraging for ingredients!

After leaving the Economic Gardens northern entrance, cross over the paved path to enter the next set of beds until you reach the lawned area. Turn right to reach a small bridge over First Creek, then turn right to walk in a northerly direction down the central path to leave the Economic Garden, then turn right until you reach the old River Red Gum tree marked, ‘Original Flora.’ (You will be able to see the North Lodge to your north-east from here.)

11. Original flora

This is a tree indigenous to the Adelaide region. It’s one of only a few trees anywhere on the Adelaide Plains that can be referred to as ‘Original Flora.’

This individual tree was already living here on Kaurna land before Europeans arrived, before the colony of South Australia was started in 1836, and well before the creation of Park 11 and the Botanic Garden changed the use of the landscape.

It’s a River Red Gum - Eucalyptus camaldulensis - and is amongst the most iconic of Australia’s trees. In 2022, the River Red was voted the ABC People’s Choice as Australia’s favourite tree. They are full of character and can be found across most of Australia.

As water lovers, they grow along rivers, creeks, waterways and in floodplains. In the ABC Catalyst documentary exploring Australia’s favourite trees, they were described as “the diviner of our landscape, plotting the watercourses all over our arid continent.”

These trees can have very long lives and may reach 1,000 years of age. Older specimens, like this one, almost always develop large hollows which can take centuries to form.

The hollows provide refuge for birds, mammals and reptiles. And the nectar from their summer flowers is very important for honey production.

The very first Director of the Adelaide Botanic Garden, George William Francis, had the foresight to retain many specimens of the original River Red gums already in existence on this land, carefully plotting them on his plan of 1855 as he designed and laid out the Botanic Garden.

Of the original River Reds that George Francis saved, there are at least two others still living - perhaps as many as five. There is another one here in the Botanic Garden, just over the other side of First Creek on Plane Tree Lawn. At least one other is in the adjacent Botanic Park.

Walk straight ahead in an easterly direction to reach the main paved path, then turn right to walk in a southerly direction to reach the large avenue of Moreton Bay fig trees.

12. Moreton Bay fig tree avenue

This impressive avenue of Moreton Bay Fig trees, named Murdoch Avenue, is probably one of the best-known features of the Adelaide Botanic Garden. This avenue of Moreton Bay fig trees (Ficus macrophylla) was planted in 1866, only nine years after the Garden opened.

Looking southward, the avenue of Moreton Bay fig trees in the 1870s, less than 10 years after they were planted.

It’s probably the oldest surviving avenue of Moreton Bay fig trees anywhere in Australia.

Although there are many specimens within the Adelaide Park Lands, these trees are not native to the Adelaide plain. They are indigenous to Australia’s east coast. They proved to be very useful in the early South Australian colony for providing a shady place to tether horses in hot Adelaide summers.

This avenue was originally intended to be an even longer avenue, extending all the way through to North Terrace. Planning changes limited it to this length, but it nevertheless remains outstanding and unique.

There’s nowhere else - even in Moreton Bay - where you can get an avenue of Moreton Bay fig trees as old and majestic as this one.

A little-known fact about Moreton Bay fig trees: they can be pollinated only by a certain species of wasp.

“Murdoch Avenue” of Moreton Bay fig trees (Ficus macrophylla)

In the wild, these trees can be parasitic, dropping seeds in the crevices of other trees and eventually strangling their hosts.

One of their biggest attractions is their huge buttress roots which not only provide kids with an irresistible place to scramble and hide, but prevent the trees from falling over in high winds and floods, while also helping the tree to gather extra nutrients.

Move back to the main path north of the Fig Tree Avenue and turn left, heading north to cross over First Creek, then turn right onto the sawdust path to enter the Australian Forest.

Continue walking through the forest, noticing the range of large, old trees. Stop when you reach a spot with some space to look around, especially at the spectacular ‘red’ trunk remains of a huge tree on your right, labeled “Ribbon Gum.”

13. Australian Forest

Pic: Botanic Gardens of SA

You are in a very shady Australian Forest which stretches out eastwards to the Bicentennial Conservatory and southwards to First Creek. It’s hard to believe you’re in the heart of the city when you go deep into this Forest.

Amongst the plants to be found here, from across the Australian continent, are some spectacular trees dating back to the original plantings of the Garden in the mid-1800s, plus some important more recent additions.

Note the remains here of an old Ribbon Gum, (Eucalyptus viminalis). This is a fast growing tree which can reach up to 50 meters in height and up to 15 meters wide at its base, with most of the bark in a living tree, rising to a creamy white trunk above this rich-colored base.

When old trees die in the Botanic Gardens and in the Parklands more broadly, they can sometimes be retained, like this one, because of their historic interest or their ongoing value in providing wildlife habitat.

The Ribbon Gum was a traditional food source for Australia’s indigenous people. It’s also known as the Manna or White Gum. You will have heard the term , ‘manna from Heaven’, which refers to a sweet resin or sap exuded by some trees, and that includes this one.

Indigenous people traditionally ate the hardened, sugary sap of this tree and they soaked the flowers in water to make a sweet drink.

Remains of a ribbon gum. Pic: Education at Botanic Garden: http://botanicgdns.rbe.net.au/

By way of caution, many plants can be poisonous if not collected and prepared properly. Indigenous people acquired knowledge over time about how to do that safely with the plants they were accessing.

You can see the remains of holes in this tree trunk. Ribbon Gums often bear these as a sign the trunks are harboring witchetty grubs. These were traditionally poked out of these holes using twigs and apparently tasting like chicken, provided a ready, protein treat.

The natural range of the Ribbon Gum is along the New South Wales and Victorian coasts, Tasmania and also here in South Australia, on the southern Yorke Peninsula and Kangaroo Island.

Walk a short distance ahead, until you reach the base or a large trunk (that looks like an elephant leg!) on a small land rise to your right.

This is the huge trunk of a Bunya Pine from Queensland.

This is one of the ancient Araucaria species that was featured at stop #8, earlier on this Trail.

Bunya pine trees (Araucaria bidwillii) are easily recognisable because of their symmetrical dome shape.

The seeds inside the Bunya pine cone are said to be delicious: a famous and celebrated example of Australian bush tucker.

Indigenous people used to travel for hundreds of kilometres to the Bunya mountains in Queensland to feast on these cones when they were in season.

The cones look like pineapples and can weigh up to 10kg, so you wouldn’t want to be standing underneath when one falls! Each tree can have up to 100 nuts.

Bunyas also produce highly valued timber, which has been used for musical instruments.

Continue walking until you reach a major intersection of three paths and stand out of the path to look up at the spectacular bottle-shaped tree in front of you.

This is a Queensland Bottle Tree Brachchiton rupestrisis (related to Kurrajong trees). You can see why this is a favourite stopping point for many visitors to this Forest. The Bottle Tree can grow up to 25 metres high and its bulbous trunk can grow up to 3.5 metres in diameter.

Queensland bottle tree in the Adelaide Botanic Garden. Pics: Alexander Barrett @anderallthethings

Quite apart from being beautiful, Bottle Trees have been very useful to humans, and resilient. Aboriginal people have used seedling roots as a food source and used the trees’ fibre to make nets. Bottle Trees become deciduous during droughts and are often left by farmers on cleared land for their value as shade and fodder trees. They adapt readily to cultivation, are tolerant of a range of soils and temperatures, and withstand bushfires, putting forth new foliage afterwards.

Walk past the Bottle Tree, continuing in an easterly direction, and follow the curve of the path left. Stop where this reaches a new small intersection of paths and turn to face west.

A Wollemi pine in the Adelaide Botanic Garden. Pic: Yaxbalam

Here’s where you can see a relatively young, but famous Wollemi Pine - Wollemia nobilis.

This tree is one of the newest additions to this Forest, but its lineage dates back to the time of the dinosaurs.

The Wollemi Pine was assumed to be extinct until an amazed bushwalker came across a specimen in the Blue Mountains in New South Wales in 1994.

The plant is now the subject of extensive research and conservation and the unearthing of this incredible species reminds us that there is still so much to discover in the plant world.

Behind it is a towering Kauri Pine - Agathis robusta - which is related to the the other ancient tree species the Wollemia and Araucaria.

Kauri pine in the Adelaide Botanic Garden. Pic: Botanic Gardens of SA

The Kauri is an evergreen coniferous tree which has glossy wide leaves, not needles, so it’s not a true pine as its common name suggests.

From the mid-19th century, European settlers highly prized Kauri and heavily logged it in northern Queensland for its high quality timber. As a result, the former large stands of these trees which were once common are now gone, although many individual trees are still found and grown further south.

Logging of Kauri pines in Queensland was eventually discontinued in 1987 with the establishment of the Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area in 1987.

The fruit of the Kauri is a favourite food of Sulphur Crested Cockatoos which frequent this Forest and the adjacent Botanic Park.

There is an even bigger Kauri specimen at the North Terrace end of the Botanic Garden, with good space all around it to be able to stand back and appreciate its magnificent size.

With a girth of around 9 meters, it’s by far the largest tree by mass in the Botanic Garden, exceeding 25 meters in height and with branches that could be trees in their own right.

We’ll now leave the Australian Forest to have a brief look at the International Rose Garden before concluding our tour with the architectural gem of the Bicentennial Conservatory, where I’ll share with you news of a proposed re-purposing of it.

Walking eastwards, leave the Australian Forest, and cross the main paved path to enter the Rose Garden.

Turn left into the upper curved path and keep following the path around until you reach the eastern end of the circular garden surrounding the statue of Queen Adelaide. Walk into the lawned area here and look back across the rose beds.

14. Roses

Pic: Michael McRoberts, Google Maps

There are two separate rose gardens here. One is the International Rose Garden; the other is the National “Trial” Rose Garden.

From this location, close to the northern fence, you can see the layout of the International Rose Garden. It includes a sunken garden, a circular garden and several pergolas, in visual counterpoint to the adjacent Bicentennial Conservatory.

In 2022, this garden was awarded the Garden of Global Excellence Award by the World Federation of Rose Societies.

This garden displays over 2,700 roses and more than 350 rose cultivars planted out in specific groupings, while mixed companion plantings add lots of seasonal colour.

Head south a short way, to the ‘trial’ beds on the central eastern side of the rose gardens.

This “National Trial Rose Garden” was started in 1996, to help the rose industry establish which varieties of rose would be best suited to the Adelaide climate. By having it here, in the Botanic Garden, everyone has an opportunity to see and smell the new roses being bred and to vote in a People’s Choice award.

Now, turn around and look westwards towards the imposing eastern profile of the Bicentennial Conservatory.

15. Bicentennial Conservatory: outside

This magnificent structure is the largest single span conservatory in the southern hemisphere.

Built to mark the bicentenary of European settlement in Australia’ (1788-1988) it was designed by celebrated architect, Guy Maron, as a purpose-built home for the Australasian Tropical Plant Collection.

The building is “curvilinear” in shape – 100 metres long, 47 metres wide and 27 metres high. An elegant steel superstructure supports almost two-and-a-half thousand square metres of toughened glass, which form the roof, walls and doors. Its distinctive shape is a landmark, particularly for airline passengers looking down at the city from above as they fly in to Adelaide.

The Bicentennial Conservatory was opened by then-Premier John Bannon in November 1989, with 18,000 people passing through on its opening day. But its establishment was fraught with controversy.

Pic: Ingrid Kellenbach

The project was conceived in 1984 with the hope of securing Federal Bicentennial funding. However, the then-Director of the Garden, Brian Morley, was faced with the key problem of finding land to accommodate it. There wasn’t a spare site within the Botanic Garden. So it was proposed that the Conservatory would be built in nearby Botanic Park.

Public opinion became so opposed to the planned encroachment on Botanic Park, it became clear that plan could not proceed.

So the State Government eventually offered, instead, this land (in Park 11) that had been occupied for about 80 years, by the former Municipal Tramways Trust.

After construction of the Conservatory, further Park Land that had been occupied by the Tramways Trust - including the area of what is now the rose gardens - was passed to the Botanic Garden in the early 1990s.

This improved the garden setting for this magnificent Conservatory - with the careful placement of tall Eucalypts along its eastern and southern sides - and also provided heritage former Tramways buildings for the Botanic Garden administration to use.

Now, walk to the northern doors of the Conservatory and move inside to the entrance space.

16. Bicentennial Conservatory: inside

Inside the Bicentennial Conservatory you'll find a lush display of lowland rainforest plants from northern Australia, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and the nearby Pacific Islands. Many of these plants are at risk or endangered in their natural habitats.

A lower walkway winds across the undulating forest floor and an upper walkway takes visitors into the canopy of trees and palms. Both walkways have full wheelchair access.

Shortly after the Conservatory was opened, it received a Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA, SA Chapter) Award of Merit (1990) and the RAIA Sir Zelman Cowan Award (1991), which is widely recognised as Australia’s leading award for public buildings.

It was also rated the 9th best building in Australia in a poll by The Australian (2010), received the Jack Cheesman Award for Enduring Architecture in South Australia (2014) and became the ‘youngest’ building in SA to receive Heritage Listing (2014).

The South Australian Heritage Council has described it as “an outstanding example of the late 20th century structuralist style.”

Ascend the walkway to take a closer look. Stop on the upper path with the lower walkway in view below.

Looking below, you can see that the lower walkway winds across the undulating forest floor and this upper walkway takes us up into the canopy of trees.

The internal environment was originally managed by substantial mechanical plant, including nearly a thousand misting nozzles in the roof to create a cloud effect, thus creating an efficient cooling, shading and humidifying system. Day and nighttime temperatures, plus relative humidity, were all maintained at levels matching the natural habitats of tropical plants.

However in 2012, the Garden undertook a review of energy costs and decided to switch off the heating. The plant collection was transitioned to that of a warm temperate rainforest rather than tropical rainforest. Many tropical plants were retained to see how they would fare, and some of them did survive the changed environment.

Now walk down the slope to the southern foyer.

Since 2023, the Adelaide Botanic Garden has been considering converting the purpose of this Conservatory to align with the goals of outer space research.

The Botanic Garden’s Strategic Plan 2023-27 says: “Our Space Botany program reimagines the Bicentennial Conservatory as a Martian Biodome, inviting students to explore botanical science as it will be practiced in the future, when humans explore options for life beyond Earth.”

The entry goes on to highlight that ‘gamification’ (digital game playing) and the unique assets of the Garden will be used to “lead the way for digital learning opportunities.”

Now head outside through the Conservatory’s northern doors, and back to your starting point, at the Conservatory Gate to the Botanic Garden, on Plane Tree Drive.

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 5.1 Mb)

All of our Trail Guides and Guided Walks are on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people. The Adelaide Park Lands Association acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future traditional custodians and elders of these lands.