Take the Trail

Start at the corner of North Terrace and East Terrace.

This Trail is on the traditional land of the Kaurna people. First Nations people are advised that this Trail Guide contains the name and an image of a person who has died.

1. Naming

2. White cedar “allee”

3. Pepper trees and Rundle road

4. Botanic Creek

5. Former wading pool; petanque piste

6. Lemon scented gums: concrete birds!

7. Central amenities

8. O-Bahn tunnel access shafts

9. Peace and Friendship Garden

10. 1879 octagonal Valve House

11. Re-vegetation

12. Adelaide Fringe Festival

13. Light Horse Memorials

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 2.7 Mb)

1. Naming

This Guided Walk starts at a collection of war memorials on the corner of North Terrace and East Terrace.

This Trail is about 1.3 kilometres in length, and should take about 75 minutes to complete. It goes around the Park and returns to this same location. Information about the war memorials (marked as number one on the map) will be the final point of interest on the Trail.

This Park’s Kaurna language name is Kadlitpina. It’s also known by its European name, Rundle Park, or simply as Park 13. It’s bounded by East Terrace, Rundle Road, Dequetteville Terrrace and Botanic Road.

This 6.5 hectare park exists today in much the same shape and form as when Colonel Light surveyed it in 1837.

The Park has some characteristics of a semi-formal Victorian Garden style, with a mix of exotic and native flora. But things have not always been so picturesque for this Park. Its position, perched on the shoulder of the city, has sometimes been a precarious one.

This park is named in two different languages, after two men with vastly different connections to the area.

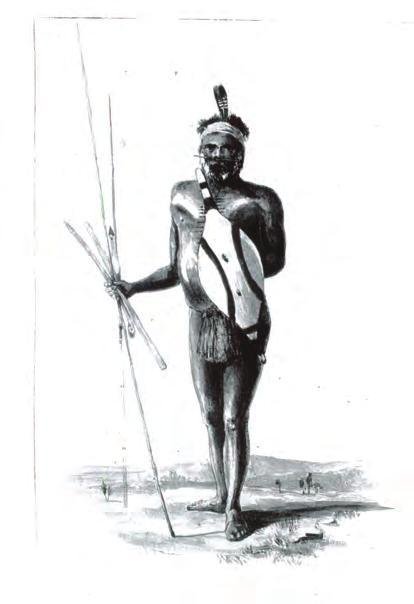

Kadlitpina was a Kaurna elder at the time of colonisation. He was known to the Europeans as Captain Jack. Regarded as a ‘military genius’, he was appointed an honorary constable and attended meetings with the Governor and other officials.

Kadlitpina was a friend of the colonists, and became a main source of information on Kaurna language and culture.

In 1838 Kadlitpina attended a ‘get to know you’ affair held for the people of Adelaide by Governor Gawler in the Park Lands, and would likely have taken part in displays of skill in activities such as spear throwing. His portrait can be found in the South Australian Museum, and on a plaque at Pirltawardli, (Park 1) on the north bank of the Torrens River, near the Par 3 Golf Course and the Torrens Weir.

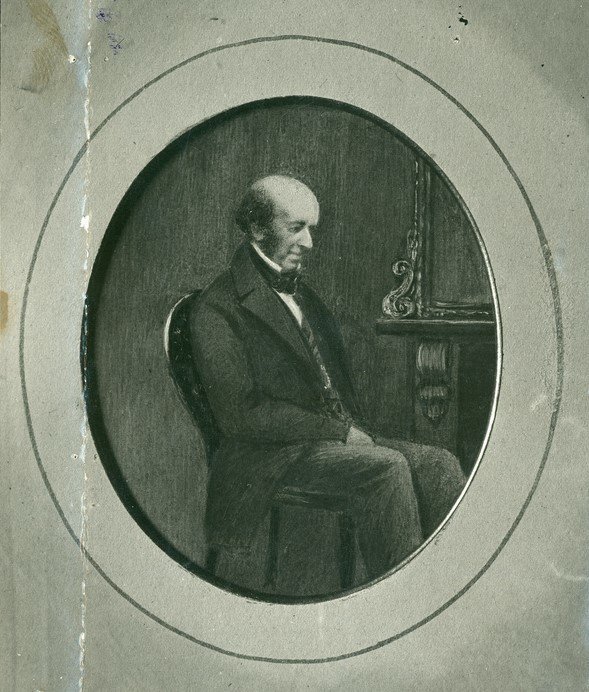

Kadlitpina (left) and John Rundle (1791 – 1864)

Kadlitpina would never have met John Rundle, after whom the park was first named in 1907. A successful businessman and a Whig member of the British parliament, Rundle was one of the original directors of the South Australian Company, which formed in London in 1835 to establish a new colony here. Rundle Rd, which creates the southern border of this park is also named after him. John Rundle, however, never set foot in South Australia.

From this point, walk down East Terrace to the intersection with Rundle Road.

2. White cedar “allee”

.

Beginning on the corner of East Terrace and Rundle Road, follow the tree-lined path into the park. This pathway [also known as an “allee”, pronounced: 'ah-LAY], lined with white cedars (Melia azedarach) and dates from the mid-1870s.

It is thought to be the first and oldest white cedar planting in the Park Lands. There is a policy to maintain the character of the pathway with new plantings.

White cedars are also known by many other names: “chinaberry”, “syringa berrytree”, “Pride of India”, “bead tree”, “Cape lilac”, “Persian lilac” or “Indian lilac”.

While enjoying the white cedars, it’s worth noting that the Park Lands have not always been as carefully tended. Following settlement in 1837, the combined effects of grazing, and unchecked clearing for timber and firewood, had turned this corner of the Park Lands into a dustbowl in summer, and a quagmire in winter. In fact, by the 1850s, this Park had been reduced to nothing more than a rubbish tip.

One letter to the editor of The Observer in 1856 described the scene:

“Hundreds of cart-loads of every description of refuse have, for a long time past, been ruthlessly scattered about upon the surface. Vegetable matter lies at leisure to decay; broken glass and bottles, mingled with old mattresses and tin-kettles; rags, bones, and dead dogs vary the scene with chemical refuse; … mingling their scents with so many others, that seventy distinct odours ... might be fairly counted over Adelaide.”

For more than one hundred years this Park has been planted out and managed in a manner consistent with its two neighbouring parks to the south - Rymill Park, and King Rodney Park.

As long ago as 1880, these three Parks were described as “Park Lands opposite East Terrace” and distinguished from the “Race Course” (meaning Victoria Park”) further to the south.

Today, these three Parks - 13, 14 and 15 are often described as the “East Park Lands”.

From here, walk along the white cedar allee and look at the old twisted pepper trees on your right, along the southern edge of the Park.

3. Pepper trees and Rundle Road

Looking West down Rundle Rd, 1876

You will notice along Rundle Road a line of ancient pepper trees. It’s not clear exactly when they were planted but it would probably have been no later than the first decade of the 20th century, so they are well over 100 years old.

Some of the ancient pepper trees along the edge of Rundle Road.

Rundle Road is built at a slightly higher level than the parks grounds on either side of the road. Its slight elevation protects it from the intermittent flooding which, in the past, would spill out from Botanic Creek.

From 1985 until 1995, Adelaide hosted the Formula One Grand Prix. The street circuit was controversial, because it would subsume the eastern Park Lands for months at a time.

Rundle Road provided a straight portion of the circuit, and was temporarily renamed for the four days of the annual event in honour of Australian Formula One driver Alan Jones.

Former Formula 1 Grand prix circuit. Source: Wikimedia. Creator: Calistemon, 1985

Controversy over the use of the Park Lands for motorsports events continues to this day.

A V8 “supercar” race was introduced in 1999, on a circuit that followed most of the old Formula One course. For 20 years, up to and including 2019, the annual race required large portions of the eastern Park Lands, for months. The V8 circuit did not include Rundle Road, but went along Bartels Rd, which separates Parks 14 and 15.

Rundle Road is very wide, and for most of the year is used extensively for car parking. Rundle Street traders were upset in 2015 when the State Government of the day proposed closing Rundle Road entirely, as it would have meant losing car parking spaces. That 2015 decision would have been of no benefit to the Park Lands however, as the plan to close Rundle Road would have seen the road replaced a bit further south, with a six-lane highway including a busway, through Rymill Park.

In 2022 Rundle Road road was closed for several months to accommodate a large shed for an “Illuminate Adelaide” exhibition.

During the annual Fringe Festival in February and March, the road is closed on Friday and Saturday nights, as well as on Sundays. In 2023, Fringe organisers sought permission to close the road for the entire six-week duration of the Fringe, so that new Fringe venues could be located on the road. The proposal met with divided popular opinion, and in August 2023, Fringe organisers then withdrew the request,

Now keep walking along the path until you come to a footbridge over a creek.

4. Botanic Creek

This park was once an area of swamp, leading into the waterhole which now forms the Botanic Garden’s main lake.

The waterlogged nature and history of flooding of this park would have saved it from becoming a quarry in early settlement, as occurred in other areas of the Park Lands.

The watercourse has been significantly altered since the 1860s to improve drainage flows. In 1916 the open storm water drains were regraded and widened. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, further drainage works were undertaken which formalised Botanic Creek as a wetlands environment.

The ephemeral Botanic Creek in Rundle Park / Kadlitpina (Park 13) pictured in 2016

Botanic Creek is being set for another major improvement over a three-year period to 2028. The project will restore Botanic Creek, developing biodiverse swales, creating new habitat and natural spaces.

Read more about the project here: https://www.adelaide-parklands.asn.au/blog/2023/8/14/creek-of-cultural-connection

This area of the Park Lands was known to the Kaurna people as kaingka wirra, meaning, ‘gum scrub’. The waterway was a major camping area for the Kaurna people, and would have provided a wealth of resources.

One indigenous man who frequented and camped in this area of the parks in the second half of the nineteenth century, the so-called ‘fringe-dweller’ Tommy Walker (Poltpalingada Booboorowie), became something of a local celebrity. The press often reported on his activities, which included frequent apprehensions for being drunk and disorderly, using insulting language, or begging.

His begging resembled a form of street theatre, into which Tommy would incorporate his latest court appearance. A renowned mimic, he entertained onlookers by parodying the magistrate bringing down a judgement and fine upon him.

Tommy died in 1901 after walking nearly 100 km from Encounter Bay to Adelaide to see the visiting Duke of Cornwall (the future King George V).

His headstone was paid for by the Adelaide Stock Exchange. It was later discovered that his skeleton had been removed before burial and sent to the University of Edinburgh for study. His remains were repatriated in the early 1990s.

From here walk across the gravel area and sit on the painted coloured steps.

5. Former wading pool; petanque piste

This unusually shaped gravelled space was previously a paddling pool, installed in 1961 for the delight of children in the hot summer months. The pool was set up here at about the same time as the ornamental boating pool across the road in Rymill Park.

The site is now used for playing petanque, a game similar to bocce or boules. The painted structure is the former pump house for the wading pool, and now provides storage and seating for the petanque players. Perhaps some of those children who once splashed around in the shallow water keep active now by returning here to play a different game.

The Park Lands Management Strategy 2015-25 proposed as one of its future strategies to re-introduce a wading pool to Rundle Park, alongside the petanque piste. However no budget allocation has been made for that purpose, since the strategy paper was endorsed in 2017. The relevant part of the Management Strategy says:

People will be encouraged to venture further into the park via a shaded, tree-lined promenade traversing the width of the park, featuring seating, artworks and drinking fountains. This promenade will connect people to a medium hub located towards the centre of the park which will provide a range of recreational facilities, including a petanque piste and an upgraded wading pool, appealing to City residents as well as visitors to the park

In 2023, the Management Strategy was being updated.

From here walk back onto the main pathway and stop at the path intersection at the very centre of the Park.

6. Lemon-scented gums: concrete birds!

Overhanging the petanque piste, this stand of lemon-scented gums (Corymbia citriodora) including one magnificent specimen dating back to the 1860s, provides home and habitat for several native species of birds.

This lemon-scented gum has the widest trunk among those in Rundle Park / Kadlitpina (Park 13). It’s believed to date from the 1860s.

However, their branches have not always held such lively examples of Adelaide’s native birdlife.

Up until the mid-twentieth century, the practice of re-vegetation in the Park Lands meant mostly Europeanisation. Flower beds and deciduous trees displaced native flora, and thus displaced native fauna. After the Second World War, people began lamenting this disappearance of native life from the Park Lands. One solution to the problem generated both public curiousity and some outrage.

In 1970, Harold Crouch, of the SA Ornithological Society, created and installed concrete birds throughout the eastern Park Lands. Hand painted by his wife, they sat in the boughs of the trees in substitute for the real thing. A control box beneath the tree would, at the push of a button, provide individual calls for several species. Public reaction was generally one of scorn at the kitsch. Crouch himself admitted as much, but stood by his models, saying:

“The idea is slightly sick… but conservation is like beating a hollow drum… the kids are the ones I’m interested in. If this teaches them to recognise and respect the birds, they may also do something to preserve them.”

Concrete birds, c 1970s

Unfortunately, the concrete birds never knew that respect, becoming a target for vandalism. Despite a conservation effort (giving them homes in higher and higher boughs) the attacks continued. By 1978 Adelaide’s concrete birds had become extinct.

Thankfully, following a change in practice towards native planting, birdlife has returned to the Park Lands. Watch for flocks of corellas digging in the grass or tearing into the pine trees; rosellas, rainbow lorikeets and galahs providing splashes of colour overhead; noisy miners and red wattlebirds defending their turf; or the New Holland honeyeater feeding amongst native flowers.

A carpet of corellas digging into the grass in Rundle Park / Kadlitpina (Park 13)

A white-faced heron (left) and an Australian white ibis (right) in Rundle Park / Kadlitpina (Park 13)

Australian wood ducks enjoying Rundle Park /Kadlitpina (Park 13)

From here, walk eastwards along the path towards the next path intersection and the toilet block.

7. Central amenities

There are two separate barbecues in Rundle Park / Kadlitpina providing opportunities for park visitors to make the most of their surrounds. The amenities here in Park 13 reflect its evolution as a place of recreation. The first public bench seats were installed here as long ago as 1907.

There are two toilet blocks in Rundle Park / Kadlitpina. The red brick toilet block, back on the corner of East Terrace and Rundle Road was erected in the 1990s, replacing a block dating from the early 1900s.

This central toilet block was erected in the 1960s using stone from Carey Gully in the Adelaide Hills, and displays what was at that time, a contemporary style.

From here, walk south-east across the grass to what look like two circular sheds.

8. O-Bahn tunnel access shafts

In 2015, the State Government announced a $160 million project to extend the O-Bahn busway from Hackney Road through the Park Lands into the city. The plan had the O-Bahn tracks running under Park 13, Rundle Road, and the adjacent Rymill Park (Park 14).

Despite protests from community groups, including the Adelaide Park Lands Association, the south-eastern corner of this Park was fenced off from the public for almost two years.

When work began in April 2016, close to 80 trees – many significant – were lost on either side of Rundle Road. The project was intended to reduce O‑Bahn travelling time by three and a half minutes.

Although described as a tunnel, it was constructed not by boring through the earth, but by cutting a wide deep trench, and then covering the trench.

O-Bahn tunnel construction underway in Rundle Park / Kadlitpina (Park 13) in 2016

The tunnel access shafts serve two purposes. They are ventilation shafts for the busway which is directly underground, and also provide an emergency access point to the tunnel if the busway is blocked.

If you look over towards Dequetteville Terrace you can see a cycle path. This was constructed in 2022, and links up with similar bikeways immediately south and north of here. The bikeway immediately south on the eastern edge of Rymill Park, was also constructed at about the same time. The one to the north on the other side of Botanic Road is several years older.

From this point, walk northwards, towards an area planted with eucalyptus trees, on the eastern edge of the Park just off Dequetteville Terrace.

9. Peace and Friendship Garden

Here in the north-western corner of this Park, you will see a rare example of formerly alienated land having been returned to Park Lands.

Adelaide’s earliest water supply was drawn from wells or bought from carters who siphoned water from the Torrens River. From December 1860, water was pumped into the city from waterworks infrastructure built in this corner of Rundle Park.

Later, in 1879, 1.4 hectares was officially removed from the park under the Adelaide Sewers and Waterworks Amendment Act. This area was further fenced off in 1906.

The location of waterworks in this Park for more than 100 years - from the 1870s until the 1980s

It wasn’t until 1984, after the phasing out of the depot, that the area was returned to Park Lands under the care control and management of the City Council.

This area was replanted in the 1980s into a native garden featuring South Australian blue gum, river she-oak, and lemon scented gums.

In 1996, this garden was formalised as the Peace and Friendship Garden, dedicated to the late President of Egypt, Anwar Sadat and the late Prime Minister of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin. Both were Nobel Peace Prize recipients. Each of them were assassinated for their efforts to promote peace in the Middle-East.

A memorial to this dedication was unveiled in the presence of the Consul-General of Egypt, Nabil Ibrahim, and the Consul-General to Israel, Mordechai Yedid.

From this point walk northwards towards a small octagonal building near the intersection of Dequetteville Terrace and Botanic Road.

10. 1879 octagonal valve house

When the former waterworks depot was removed in 1984, one of its relics was retained. This original octagonal valve house, dating from 1879, was re-located 20 metres from its original location (further back from the intersection of Dequetteville Terrace and Botanic Road) and restored as a reminder of its previous role, generations ago, in the first flow of Adelaide’s mains water.

The valve house in 1932, in its original location. Pic: State Library of SA

The 1879 valve house in Rundle Park /Kadlitpina (Park 13)

The fact that this valve house was demolished, moved and then re-constructed here in 1984 was relevant again decades later.

In 2022, the State Government demolished a heritage-listed old Gate House at Urrbrae on the corner of Fullarton Rd and Cross Road to accommodate widening of that intersection.

Many people objected and some suggested that the old Urrbrae Gate House could be moved, just like this Valve House had been moved in the 1980s. In the end, that was how the project was proposed to proceed. In 2023, it was relocated several hundred metres away, within the University of Adelaide Waite Campus, along Claremont Avenue, Urrbrae after the completion of the intersection works.

From here, walk south-west back into the Park along the bitumen path that, like the earlier path, is lined with white cedar trees.

11. Re-vegetation

.

As mentioned earlier, the Adelaide Park Lands were stripped of nearly all trees in the two decades after European settlement in 1837.

By 1850, public opinion had concluded that something needed to be done about the barren and unappealing aesthetic of all the Park Lands, including this park.

Olives became one of the most widely planted trees by the 1870s, because of their fast growth and productivity. There is still a small grove of them in the north-west corner of Rundle Park, but not as many as you will see in other parts of the Park Lands.

In the late 1800s, two consecutive city gardeners (O’Brien and Pengilly) carried out planting of mainly British and Mediterranean species, but in an ad hoc, un-ornamental fashion.

A report written in 1880 describes the chief species in the eastern parklands being pines, olives, and eucalypts. The report also recommended the removal of most of these gums and olives from this Park 13, to begin a more ornamental planting strategy, one which would complement the existing white cedars and create a semi-formal garden environment.

The report’s author, John Ednie Brown, was appointed ‘Supervisor of the Plantations’, and Pengillly, the city gardener was placed at his disposal. Tensions between the two men, one who was appointed to overturn years of the other’s work, quickly reached a head, and they had a falling out. Brown quit, citing concern for his professional reputation, and Pengilly was later fired.

The dust eventually settled, and from the beginning of the 20th century, new city gardener August Pelzer began removing failing olives and conducting a vigorous replanting of Aleppo pines, plane trees, and English elms – in accordance with Brown’s recommendations.

The planting program upheld the formal garden character of Rundle Park / Kadlitpina (Park 13).

Tree-lined pedestrian avenues contribute to the formal garden character of this Park

Along the northern edge of the Park, beside Botanic Road, you can see the results of their planting work more than a century ago: towering specimens of Aleppo pine trees. The Aleppo Pine is a large, fast-growing, evergreen tree that invades native vegetation. It is the same species as the Lone Pine at Gallipoli and has been planted widely in Australia at war memorial sites (of which Park 13 is one).

Towering Aleppo pines along Botanic Road on the northern edge of Rundle Park / Kadlitpina (Park 13)

Aleppo Pine is a “declared weed” species. That does not mean that these specimens are in any danger of removal. However, when they die it is unlikely that they would be replaced with new Aleppo Pines.

Further down the slope there are some English Elms of a similar vintage.

English elms (foreground) and European olive trees (in the background, near the north-western corner of Rundle Park / Kadlitpina (Park 13)

From here, walk back to the bridge that crosses Botanic Creek.

12. Adelaide Fringe Festival

For 31 days in February and March every year (since 2006), this Park has been given over to the Adelaide Fringe Festival.

Masquerading as the “Garden of Unearthly Delights”, this park is fenced off and filled with temporary venues for theatre, comedy, cabaret and other performances, as well as food stalls and a carnival. Around 800,000 visits each year mean that The Garden of Unearthly Delights is one of Adelaide’s most popular places every summer.

For several months in late 2020, this Park was fenced off from the public while work crews were upgrading underground infrastructure (power, recycled water, sewer) to better support The Garden of Unearthly Delights and other events that use this Park from time to time.

The works were successful which means that for events in Rundle Park, there is less need for noisy mobile generators. There is also increased availability of recycled water (from the North Glenelg Wastewater Treatment plant) to service temporary toilets and other non-drinking supplies.

After the fences came down, all of the upgraded infrastructure was installed but invisible underground. Similar works were carried out in the neighbouring Rymill Park, from June to October 2022,

From here, walk back to the starting point of the Trail, on the corner of North Terrace and East Terrace.

13. Light Horse memorials

Here, in the north-eastern corner of this Park there are several war memorials.

The large white granite obelisk was dedicated in 1925 to members of the Australian Light Horse Regiments who died in World War One.

The horses themselves are also remembered, with a white granite drinking trough. Historians have noted that this memorial to war horses was erected long before there was any monument to Aboriginal Australians who were in military service.

ANZAC Day - carrots left for horses at the drinking trough war memorial

The rectangular white granite memorial with a bronze plaque was added in 1995 by the successors of the Light Horse Regiment – the Royal Australian Armoured Corps – to record the 50th anniversary of 'Victory in the Pacific” (VP) Day.

In 2002, a bronze plaque was added to the obelisk to commemorate the passing of Private Albert Whitmore (aged 102), who was the last surviving Australia Light Horseman and the last surviving South Australian World War I veteran.

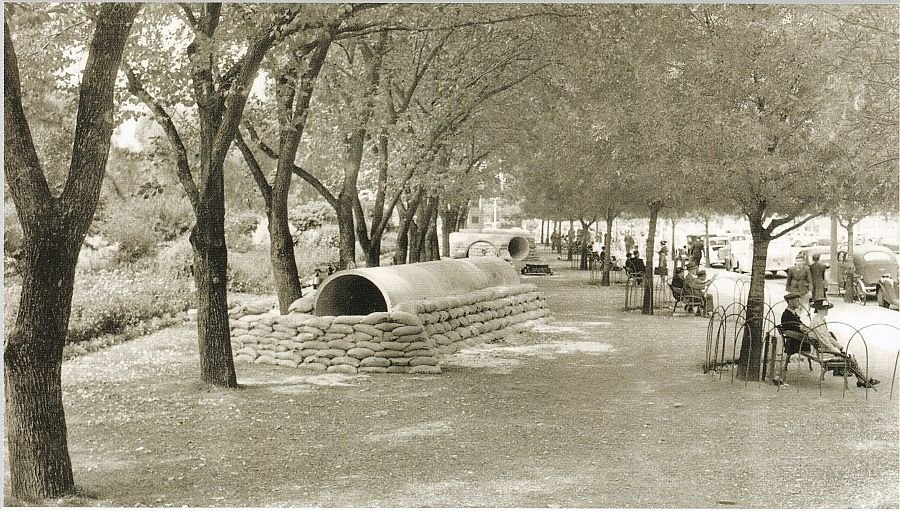

War itself never reached Adelaide, but even the Park Lands were not immune to the perceived threat of attack. From 1942 to 1944 a series of air raid shelters was built in the Park Lands – five-foot deep trenches reinforced with sandbags and cement pipes.

This Park hosted the largest network of these shelters. There's no sign of them today, but at the time, over two kilometres of trenches, arranged in a herringbone pattern, had a capacity of 2,500 people. Thankfully, they were never used for their intended purpose, though they did become a handy place for romantic couples to rendezvous.

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 2.7 Mb)

All of our Trail Guides and Guided Walks are on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people. The Adelaide Park Lands Association acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future traditional custodians and elders of these lands.