Take the Trail

Start at the corner of West Terrace and Wylde Road.

This Trail is on the traditional land of the Kaurna people.

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 1.95 Mb)

1. Introduction and Naming

This Park is called G.S. Kingston Park, also known as Wirrarninthi or simply Park 23.

Park 23 is 57 hectares. It's bounded by Anzac Highway to the south, West Terrace to the east, Sir Donald Bradman Drive to the north and the Railway lines to the west. The park is broken into three sections; the northern and southern portions being split by the West Terrace Cemetery.

It's named after Sir George Strickland Kingston, who was the deputy suveyor to Colonel Light in 1837 as Adelaide was laid out. Kingston was an engineer, architect and surveyor who was responsible for the design of several significant Adelaide buildings and the first monument to Colonel Light. Later, he became the first Speaker in South Australia’s House of Assembly.

He was an establishment figure, walking city streets with a silver-topped cane. Kingston lived in nearby Grote Street.

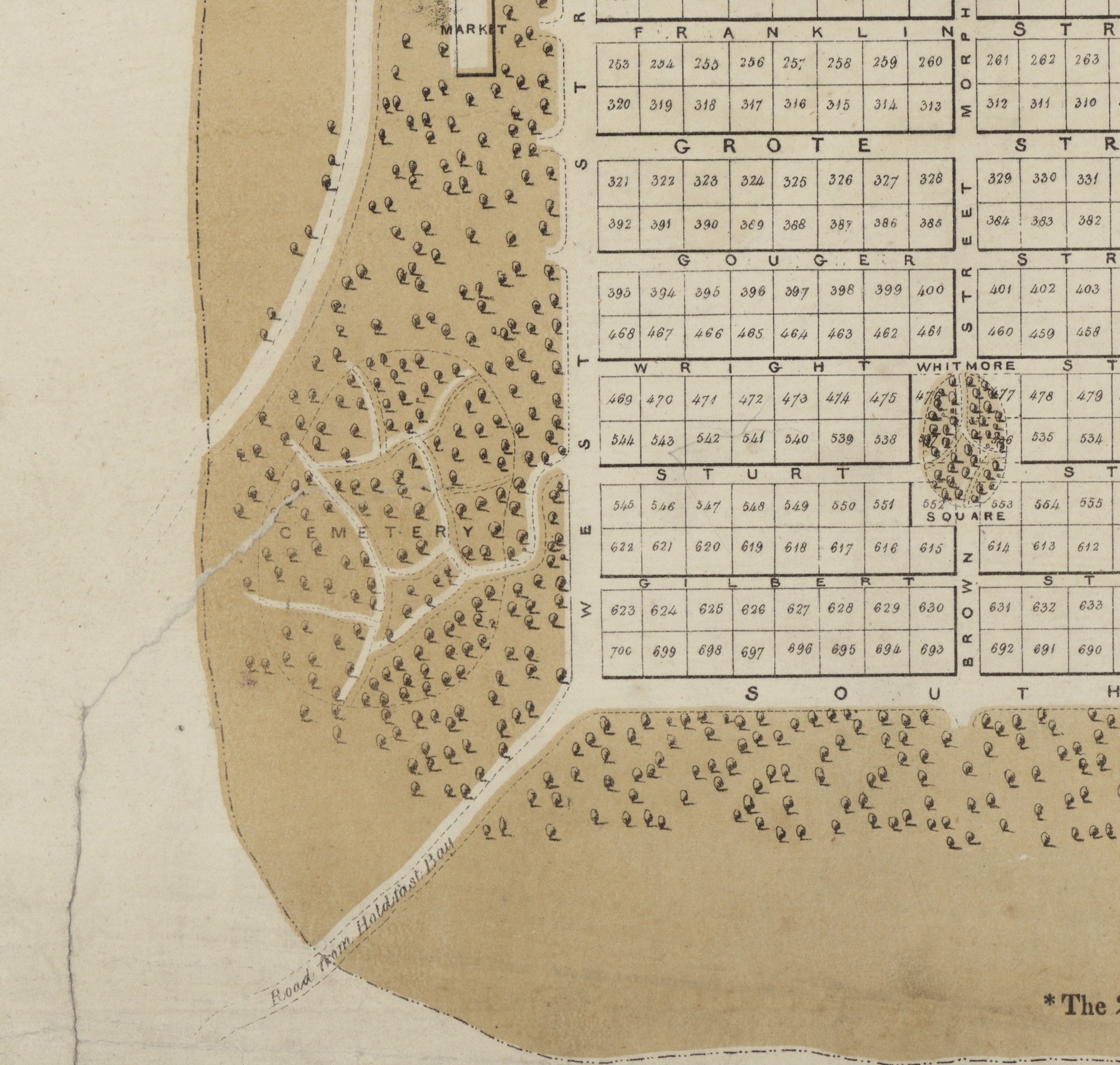

A 1936 aerial photo (left), and Colonel William Light’s 1837 plan for the south-western Park Lands (right)

In 2002 this Park 23 was named “Wirranendi.” In 2013 the spelling was revised to “Wirrarninthi” which better represents correct pronunciation of the Kaurna name. The name means to ‘become transformed into a green, forested area’. The Park has been transformed over decades, as you'll see on this Trail.

Park 23 is so large that this Trail Guide is confined to the northern section of the Park, and the West Terrace Cemetery. This Trail Guide does not include the southern portion of Park 23, alongside Anzac Highway (known as “Edwards Park”) but that is included in a different Trail Guide:

From here, walk across Wylde Road and stop behind the playground, to view both the playground and the sporting fields off Wyle Road.

2. Playspace and sports oval

.

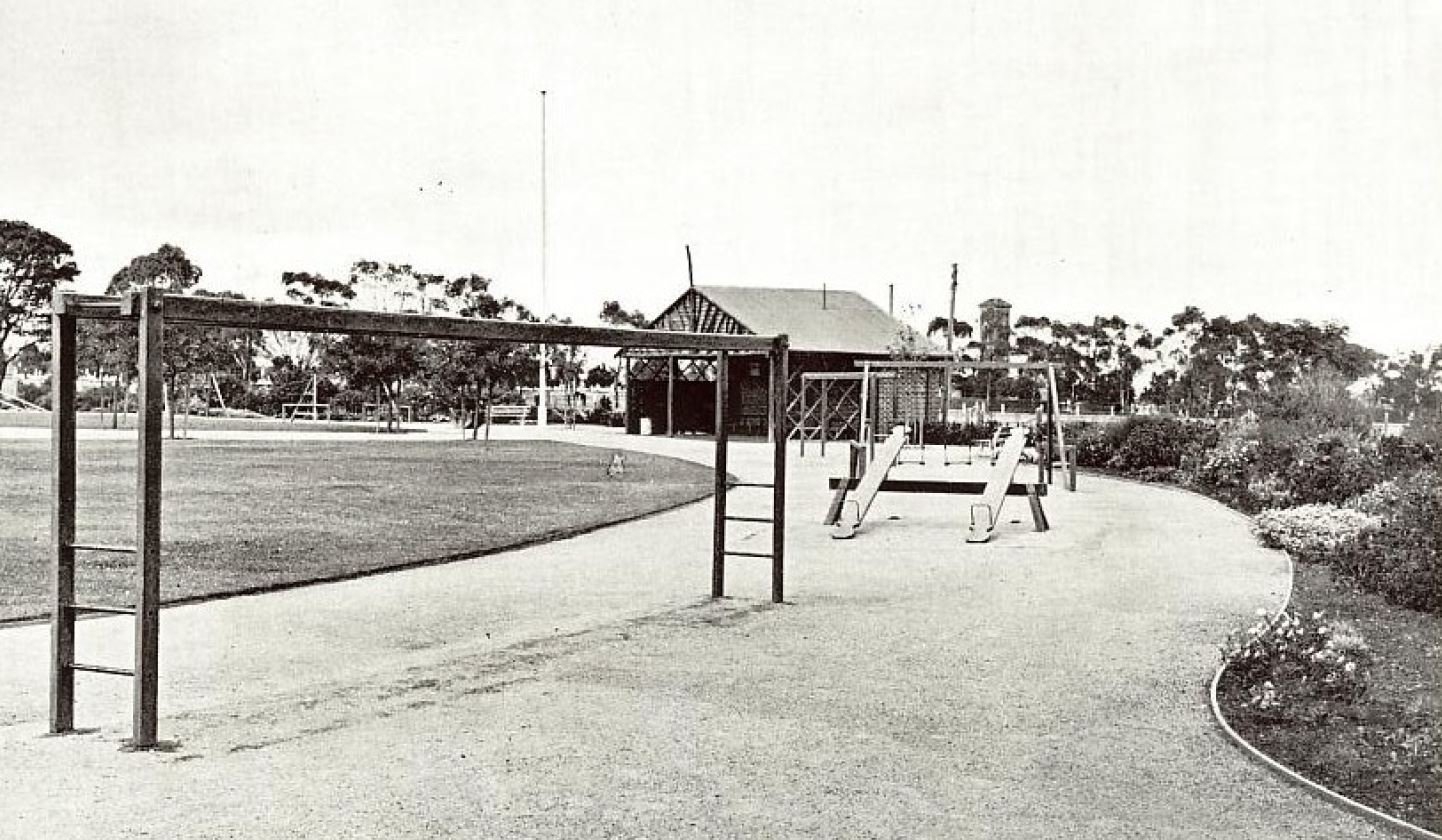

This area of the Park hosts a children’s playground that has undergone many renewals since its creation in 1924. It now contains a climbing web with slide attached, junior fort, sandpit, spring rides, double swing and bucket swing.

In the early 20th century the establishment of playgrounds in the city was a focus of community debate. At the opening of this playground in 1924, the Governor, Attorney-General and the Lord Mayor were welcomed by a guard of honour of children from local schools. A pipe and drum band played, while the children sang the national anthem and performed a dance.

The West Terrace playground photographed in 1928. Images: City of Adelaide Archives

At that stage, the playground was surrounded by fencing to keep out grazing livestock. It was also divided by age and gender.

By 1928 the playground had a full-time supervisor paid by the Education Department. The supervisor had a direct telephone line to the police. They playground was hosting more than a hundred children every day – some days over 200.

A City Council document published in November 2024, says that this playground was frequented by Aboriginal children living in the West End of Adelaide during the 1930s to 1950s.

There are six particularly large specimens of Aleppo Pine (Pinus halepensis) trees located adjacent to and within the West Terrace Playground.

Park 23 has a long association with sporting activities. Looking west behind the playground you will see a painted brick building. Built in the 1960s, it includes both clubrooms and toilet facilities.

The playground toilet block and clubrooms as it looked in 2017 (left) and in 2007 (right).

Behind that building is an oval that was constructed in 1936. It was named Bone Timber Reserve after the council’s Director of Parks and Gardens Mr Bone. Today this oval and clubrooms hosts the Adelaide Cricket Club.

Sporting activity in Park 23 hasn’t been without controversy. From the 1920s, some Protestant church groups pressured the council to ban the playing of sport on the Sabbath.

In 1939 the council passed a regulation effectively banning organised sport in all of the Park Lands on a Sunday. The ban continued until the Dustan Government removed it in 1967.

From here, walk a little further north to Kingston Gardens and the bandstand or rotunda.

3. Kingston Gardens

Kingston Gardens is a great spot to relax while still being close to the heart of the city. In the first decade of the 20th century, the development of Park 23 began here, on a 1.2 hectare site at the intersection corner.

The gardens were named after politician George Strickland Kingston. In 2017 the City Council decided to extend the name G.S. Kingston to cover not just these gardens, but also the whole of Park 23.

The centrepiece of Kingston Gardens is a bandstand or rotunda It was opened in 1909. The area was also fenced off and planted with trees, shrubs and flowers, and electricity connected for lighting of the bandstand. At the time, in 1909, The Advertiser reported that 3,000 West Adelaide residents attended the opening of the gardens.

In 1912 Kingston Gardens bandstand became a venue for Wattle Day celebrations managed by the Kindergarten Union of South Australia. The bandstand was used regularly for concerts and events from the 1920s until the 1940s. From then it has served largely as an ornamental structure in the park.

The Kingston Gardens rotunda at night (left) and as it looked in 1928 (right, from City of Adelaide archives).

According to academic David Jones (2007) some of the significant trees in Kingston Gardens included (at the time he was writing):

a Hoop Pine (Araucaria cunninghamii) probably planted in the 1960s

a Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera);

a Pepper Tree (Schinus aeria var molle) along the edge of West Tce in the Kingston Gardens precinct that pre-dates the development of Kingston Gardens;

an arc of eight American Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) planted by Pelzer during the very early 1900s when the garden and adjacent playground were established.

How many of these can you see remaining here?

From this point, turn left and walk along the path beside Sir Donald Bradman Drive. You will pass two trees that are on the edge of the road, to the right of the footpath. The first one is a Port Jackson fig; the second a blue gum. Stop when you reach a collection of stone domes.

On the way to stop #4 you will pass native vegetation including examples such as this decades-old Port Jackson fig tree {Ficus rubiginosa) that has been protected from road widening, with kerbing being laid around it.

4. Lie of the Land

These stone domes are one-half of a public art installation, called the “Lie of the Land”.

The domes are on both sides of Sir Donald Bradman Drive - in both Park 23 and in Park 24.

The domes are made of Kanmantoo stone. They were inspired by this drawing in the SA Art Gallery of indigenous Australians camped near Adelaide at the time of European settlement.

Drawing (1858) by Eugene von Guerard: “Winter encampments in wurlies of divisions of the tribes from Lake Bonney and Lake Victoria in the parkland near Adelaide”

Prior to European settlement Kaurna people hunted and gathered food, medicinal plants and material for their shelters in this area.

There was a design competition in 2001 to create a “Gateway Statement” for people arriving in Adelaide, from the airport. This proposal, the “Lie of the Land” was the winning entry by artists Jude Walton and Aleks Danko.

The official opening was by former State Government Minister John Hill in 2004. You can read more about these sculptures here: https://www.adelaide-parklands.asn.au/blog/2023/6/25/know-your-park-lands-art-lie-of-the-land

From this point walk a few metres further west, and turn left into the Park on Catholic Cemetery Road. Stop where you see this stone entry sign (pictured below).

5. Environmental trail (entry)

Perhaps the best-kept secret of your Adelaide Park Lands, this tranquil and educational trail meanders through a young urban forest, flanked by sculptures and carefully crafted engraved rocks.

The “Wirrarninthi Environmental Trail” - as marked on the map below - is a loop that is 2.1 kilometres long. It does not include any part of the West Terrace Cemetery.

“Wirrarninthi Environmental Trail” is described in a leaflet published by the City of Adelaide. Copies of the leaflet are sometimes available here, at the entrance.

The Wirrarninthi Environmental Trail has four themes: – earth, wind, water, and fire – each having their own area of the trail.

Sculptures and other public artworks reflect the theme of each area, while smaller stones have images which school aged children can use to create rubbings. It is a valuable area for biodiversity, with wood ducks, parrots of all colours and a variety of indigenous plants.

Near the entry sign is a rock sculpture of an albatross chick that died after being fed bits of floating rubbish that its parents apparently had mistaken for fish.

Rock sculpture of an albatross chick

Albatrosses spend most of their lives far out at sea. They feed on fish and raise their young on islands far from where many people live.

One of the themes of this environmental trail is how our own actions can affect the environment – not just where we live, but also a long distance away from us. Think about:

How the chick’s parents found so much rubbish so far from people?

What are some ways we can be more responsible for our waste and recycling?

From the entry point here, walk westwards towards the railway line, then turn left and follow a dirt trail southwards alongside the railway line.

Participants in an APA Guided Walk in 2021, heading westwards towards the Fire Sculpture

6. Fire sculpture

A short distance south from Sir Donald Bradman Drive, you'll see a series of carefully arranged stones known as the Fire Sculpture.

This sculpture depicts marks that animals and humans have left in Wirrarninthi over time, especially those things that may have remained after periodic fires.

The markings on the sculpture show the footprints of animals that may have passed through the area since before European settlement until now. The bones and rubbish around the circular base show how changes in culture and technology have changed the marks people leave on the land.

Stopping at the fire sculpture during an APA Guided Walk in 2021.

It reminds us of the impacts of European settlement since 1837. In the 1860's, this park was fenced in white-painted timber post and wire. By that time (the 1860s) most of the native vegetation had been effectively removed.

In the 20th century, before the Wirrarninthi environmental trail was established, you might once have come across gum trees, open space, campsites, a quarry, horse, cattle or sheep grazing, or even a rubbish tip.

Keep walking south alongside the railway line until you come to another stone sculpture. Following the trail south, you will see the railway lines on your right and (unless recent weather has been very dry) you’ll see a wetland area to your left.

The wetland you will see to your left as you walk south between the fire sculpture and the wind sculpture. A City Council 2024 biodiversity report notes that the waterhole has few fringing reeds and rushes due to trees and shrubs shading the edge, but there are native sedge and rush species.

7. Wind sculpture

The two adjacent rock sculptures are intended to be evocative of wind. How do you make wind into rock art?

You cannot see wind. However, you can experience the wind in other ways.

Close your eyes and listen to the wind and the sounds in the park, smell the air, feel the breeze in your hair. Imagine how it might feel to be a bird soaring in the sky.

The larger of the two wind sculptures next to the railway lines.

If you look carefully at the two sculptures you might discern a plastic bag depicted on the smaller of the two rocks. This is a reminder that what we throw away sometimes gets carried by the wind and can do harm to animals or birds who might eat it or get trapped by our rubbish.

From here, the trail curls past the wind sculpture before turning east and skirting the wetland and creek bed to meet up again with Catholic Cemetery Road.

8. Cat and possum sculptures

At this point you are at the intersection of the Wirrarninthi Environmental Trail and Catholic Cemetery Road.

There are distinctive bronze statues of a cat that has caught a bird and (a nearby) lizard; a comment on the problem of pet cats hunting native animals in Australia.

The sculptor Silvio Apponyi, is famous for his native animal sculptures.

Domestic cat with bird: sculpture by Silvio Apponyi on the Wirrarninthi environmental trail

Cats are often given the run of a house and yard. A cat may be trusted to come and go as it pleases, only drawing attention when it brings home a dead bird, as a gift.

Cats are such common animals that people may forget there were no cats in Australia before European settlement. Cats may be cute and cuddly, but they are also highly effective predators and have contributed to the decline of small animals around the world.

Immediately to the north of the cat sculpture is a native bee nesting house built by community volunteers as part of the River Torrens Recovery Project. Native bee “hotels” and native food plants can be found at a number of locations along the River Torrens to provide bees with more places to live and forage. You can use the sign, next to the bee nesting house, to try to identify any bees you might see nesting here.

The native bee hotel, immediately north of the cat sculpture.

Cross over the bitumen road (Catholic Cemetery Rd) and head up the gentle grassy slope to the next sculpture, of a possum.

This is another sculpture by Silvio Apponyi. He has a very similar possum sculpture in Possum Park / Pirltawardli (Park 1).

Silvio Apponyi’s two possum sculptures in your Adelaide Park Lands. At left: here on the environmental trail in G.S. Kingston Park / Wirrarninthi (Park 23) and at right: in Possum Park / Pirltawardli (Park 1) near the Par 3 golf course entry off War Memorial Drive.

Possums are one type of Australian mammal that has adapted well to living in urban environments. They are commonly seen in parks and neighbourhoods throughout Adelaide.

Hundreds of possums are scattered about your Adelaide Park Lands, but they’re spread out very unevenly. Some parts of your Park Lands have few, or no possums, but the greatest concentration is in Whitmore Square!

The Adelaide Park Lands are home to both the Brushtail Possum and the Ringtail Possum. Which kind of possum do you think this one is?

From the possum sculpture, walk across the grass, south-east towards a narrow dirt trail, in the direction indicated by these arrows. Keep walking on a narrow dirt trail, with the wetland on your left and the cemetery wire fence on your right.

After about 400 metres walking through the bush, you will come to a wooden bridge over the creek. Cross over the wooden bridge.

9. Water and duck sculptures

As clouds, rain, rivers and oceans, water brings life to ecosystems as it cycles through the environment.

Water shapes the land as it flows, carrying soil and nutrients downstream. Organisms of all kinds flourish in the currents and tides of water. Humans use water for transport, store it for farming, and sometimes harness its flow to generate power. Often, water also carries our rubbish and other waste.

After you cross the wooden bridge, you will see this water sculpture to your left.

These wetlands include native plants, which attract native birds and animals.

They filter stormwater and runoff from the city’s air-conditioning systems.

This water sculpture depicts a variety of aquatic plant and animal species that are often difficult to observe from land.

What are some of the plants and animals you can see in the sculpture?

From the water sculpture, walk south for about 20 metres. Depending how much rain there has been recently, the next item, a duck sculpture, might be surrounded by water or muddy ground.

This is a sculpture of Australian wood ducks, also known as the “maned duck.” They are very common in your Adelaide Park Lands.

Wood ducks provide an example of how complex interactions in the environment can be. Wood ducks can help transport other animals and plants between habitats. Sometimes plants and seeds eaten by the ducks survive undigested to grow wherever the birds travel.

Eggs of water insects and fish may also stick to a duck’s feet or feathers and be carried to new habitats where they can grow and become part of the ecosystem.

The duck sculpture might be hard to spot, hidden behind trees, on ground that might be flooded or muddy if you are visiting after recent rain.

Therefore, as ducks travel in search of food, they can bring greater biodiversity with them.

From the duck sculpture, turn around and go back northward, past the wooden footbridge. Keep walking until you reach a pathway junction, with this rock sculpture (pictured below) near the corner of the dirt paths.

10. Earth discovery area

The Wirrarninthi Environmental Trail includes most of what the City Council describes as one of the few “Key Biodiversity Areas” in your Adelaide Park Lands.

A City Council 2024 biodiversity report identifies all of this area between the West Terrace Cemetery, and Sir Donald Bradman Drive as one of the few ‘Key Biodiversity Areas’ in your Adelaide Park Lands.

A Park Lands Management Strategy “Towards 2036” which was endorsed by the City Council in November 2024 includes, as a Target: “Improve the revegetation and habitat qualities of [this Park] to support its classification as a Key Biodiversity Area.”

This Mallee Box woodland in the “Earth zone” resembles what the Adelaide Plains would have looked like before the city was founded.

Earth provides a solid base for plants to grow, which in turn provide the start for most food chains. Plants like the many types of wattle trees in the area provide food and shelter for people and animals.

In the past, the Kaurna people ground wattle seeds into flour for food. Can you see any wattle trees nearby? They may have small seedpods shaped like pea pods.

Some of the 10 discovery rocks in the Earth zone.

There are 10 discovery rocks in the Earth zone—can you find them? What kinds of animals are on the discovery rocks? (Be careful not to walk on the mulch around the discovery rocks; some of these tiny creatures might may be hiding there, and could get hurt if stepped on!)

From this point turn left, and follow the dirt road westwards, parallel to Sir Donald Bradman Drive. By the side of the dirt road you might see native plants such as this one:

On the way to stop #11 you will pass native vegetation including examples such as this hardenbergia (native lilac) that flowers during winter.

When you reach the sealed Catholic Cemetery Road again, turn left, and head south on Catholic Cemetery Road until you reach this rock, in between two bench seats (pictured below).

11. Poem rock

Carved into this rock rock is a poem, “Wirranendi” by Kimberly Mann. (Wirrandendi was the former spelling of this Park’s Kaurna name. It was changed in 2013 to “Wirrarninthi”.)

Read the words and think about your journey around the trail.

From here, walk south, past the cat sculpture and stop at the entrance to West Terrace Cemetery.

12. Cemetery entrance

You are now standing at the northern entry to the Catholic Section of the West Terrace Cemetery. The cemetery is an integral part of Park 23 and remains Australia’s oldest still-operating metropolitan cemetery. It was designated in Colonel Light’s original 1837 plan for Adelaide.

Over the years - as growth and demand has occurred - portions of Park 23 have been added to the size of the Cemetery. It initially comprised an area of 13 hectares. The total area today is more than double that - 27 hectares. That means that the cemetery occupies just under half of Park 23. That is, 27 hectares out of the Park’s 57 hectares.

West Terrace cemetery is divided into a number of sections for various communities and faiths, including two Catholic areas, as well as Jewish, Afghan, Islamic and Quaker sections. The first burial took place in July 1837 and there are more than 150,000 internments.

It is often described as the most significant cemetery in the State because it contains the remains of many of the citizens who helped shape the origins of South Australia. It is officially classed as one of the dozen most significant burial grounds in Australia.

Many Indigenous people have been buried in the cemetery and there's a sad history of grave-robbing of several Aboriginal bodies.

The biggest scandal occurred in 1903 when State Coroner Dr William Ramsay Smith was found to have robbed several graves, including the remains of Ngarrindjeri identity Tommy Walker. In 2003, his remains were retrieved from the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, and his relatives have reburied them.

From here, walk into the Catholic section, and turn left at the path junction. Stop at the small octagonal stone chapel.

13. Smyth Chapel

This Roman Catholic “Smyth Chapel”, erected in 1870, is on the State Heritage Register and is a memorial to the Very Reverend John Smyth. A building of this form and style is rare in Australia.

It is a graceful, octagonal, early gothic revival chapel with pointed roof terminating in a fleche. The walls are bluestone with slate floors and steps, and sandstone “grotesques”; the roof covering is of corrugated iron.

1870 Smyth chapel

From this point, walk east towards the gates on Wylde Road, then turn right into the cemetery and look for the small signposted Quaker section.

14. Crematorium ruins

Adelaide can lay claim to many things, but perhaps one of the least known claims is that of being the home of the first crematorium ever built in the southern hemisphere.

The crematorium was built here in 1903. These days cremation is very common but back then South Australia was the first State in Australia to legalise the procedure.

The crematorium had an underground furnace room, a single cremation chamber and a chimney that was designed to look like an Italian bell-tower.

The crematorium in 1919.

In the early days it was difficult to heat the furnace sufficiently hot to disintegrate the entire body and bones. They used gas coke (a fuel with a high carbon content but little pollution from burning) and mallee firewood.

The Crematorium used dead animals, such as sheep, to practice upon to make sure they got their temperature high enough, and their procedures right. The first human cremation attracted a crowd of about 200.

In its early days the crematorium saw barely any use, but soon it became popular, and before its closing in 1959, after 56 years of operation, it had been used to cremate the remains of 4,762 people.

The building was demolished in 1969. In recent times, archaeologists have tried to uncover the foundations of the building. They found the furnace intact underground, along with bricks, and scraps of metal and a damper for the chimney.

Visiting the crematorium ruins on an APA Guided Walk

From the crematorium ruins, head west for a few metres and look for the modest “Quaker” section of the cemetery, and a green rubbish bin.

There is no signage but this area on the edge of the Quaker section is the site of a few rare native apricot trees which fruit in late autumn and winter.

Most of the trees within the Adelaide Park Lands were planted after European settlement, and chosen by various Adelaide City gardeners over the years. However there are some remnant native species that still exist having survived, despite human intervention.

These trees have a variety of common names: weeping pittosporum, butter-bush, cattle bush, gumbi gumbi, or berrigan. Here in Adelaide it is called a native apricot. The native apricot grows mostly in inland Australia. It’s a slow growing plant, usually growing between two and six metres high, although some can reach ten metres tall.

A native apricot tree fruiting in the Quaker section of the West Terrace Cemetery, Park 23.

It is drought and frost resistant. It can survive in areas with rainfall as low as 150 mm per year. It is resilient. Some trees may live for over a hundred years. These ones would have sprung up from the seeds of others in the same area.

Its bright orange fruit is bitter – not pleasant eating. Native vegetation laws prevent you from sampling it. Apart from these two specimens there is another grove you will see in a few minutes further into the cemetery, and a larger native apricot tree in the next Park, north of here – Park 24. The one in Park 24 is believed to be the largest native apricot tree growing wild anywhere on the Adelaide plains. A few other isolated specimens are in other Parks, including in revegetated bushland areas of Golden Wattle Park / Mirnu Wirra (Park 21 West); and Yam Daisy Park / Kantarilla (Park 3).

From here, walk south between the graves, along Path 19 West until you get to “Road One.”

15. Memorials to famous South Australians

The West Terrace Cemetery offers tours of the cemetery – both during the day and after-dark tours. It is beyond the scope of this Trail Guide to highlight all the famous grave sites here, but here on “Road One” you are close to several prominent grave sites.

Near the corner of Path 19 West and “Road One” is the tombstone of Francis Faulding – the Adelaide founder of what become the multinational Faulding Pharmaceuticals company.

Very close nearby, a few paces to the east (i.e. towards West Terrace) is the Glover family resting place. Two of the Glovers, father and son, were each Lord Mayor of Adelaide, about 50 years apart, during the early and mid 20th century.

Now resume walking south, between the graves, along Path 19 West until you get to “Road Two” and look for a sign indicating “Heritage Protected Remnant Native Vegetation.”

16. Quandong grove

Nestled among gravestones just off Road Two in the West Terrace cemetery is some of South Australia's best “bush tucker”. Quandongs are also known as desert peach, native peach or wild peach.

They're in season from August to December with bright orange-red fruit. The taste is tart and tangy, and sweetness varies greatly between trees.

Quandong trees used to have a wide natural distribution throughout southern Australia from arid desert areas to coastal regions. It was an important native food source for Indigenous Australians across semi-arid and arid regions in the mainland states, with surplus fruit collected and dried for later consumption. Amongst the male members of Central Australia’s Pitjantjatjara people, quandongs were considered a suitable substitute for meat.

This is one of very few, possibly the only place on the Adelaide Plains where quandong bushes are growing wild.

Step back onto Road Two, then head west on the bitumen road towards the railway line. Near the T-junction, there is a flagpole marking the site of another famous South Australian.

17. Song of Australia

This is the grave of Carl Linger. Helping to form Adelaide’s first Philharmonic Orchestra, Carl Linger became a key figure in the development of Adelaide’s musical culture. But it was Linger’s composition of the Song of Australia for which he is best known.

Paired with lyrics written by local poet Caroline Carleton, the Song of Australia became very popular in South Australia, being sung in all public schools from the 1880s until the late 20th century. There was a suggestion at one time that it should become the national anthem.

There is another grove of native apricot trees near the Carl Linger memorial. Can you see them nearby?

From this point, head south towards the military section of the cemetery. Passing the Afghan and Jewish sections, you will soon come to a T-junction where you will see the Australian Imperial Force Cemetery.

18. AIF cemetery & Cross of Sacrifice

This was Australia’s first dedicated military cemetery, opened in 1920, just after the massive casualties of the First World War from 1914 to 1918. It was known at the time as the “Great War”. It had a profound impact on all of Australian society.

There are more than 4,000 graves here in this section, but no more graves have been added since 1994.

Pic: State Library of South Australia

The Cross of Sacrifice at the centre was a gift from the Federal Government. It was the first of its kind to be erected in an Australian cemetery. It is made of marble, quarried at Angaston in the Barossa Valley. It was unveiled in 1924 by the then Governor General. The cross stands 10 metres tall.

Together the cross and bronze sword embody the military character and spiritual nature of the cemetery.

There is more of Park 23 south of here. The Park continues south from the cemetery, into an area off Anzac Highway including open woodland and former netball courts known as “Edwards Park”. But that area is covered in a different one of our Trail Guides:

From here return back along the southern boundary of the cemetery to the main entrance gates on West Terrace, opposite Sturt Street.

From there, walk along the West Terrace footpath back to your starting point on the corner of Wylde Road.

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 1.95 Mb)

All of our Trail Guides and Guided Walks are on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people. The Adelaide Park Lands Association acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future traditional custodians and elders of these lands.