Take the Trail

Start at the corner of Melbourne Street & Mann Road.

Approximately 4 km - allow about two hours

This Trail is on the traditional land of the Kaurna people.

Stops on the Trail

1. The Olive Groves - introduction

2. Infrastructure

3. 1856 Olive plantation

4. The narrowest parks

5. Red gum fights against disease

6. Olive oil industry

7. A treasure or a weed?

8. Diversity of other trees

9. Park 9 naming

10. South-east corner

11. Sports facilities

12. Bushland trail

13. Playspace and community hub

14. McKinnon Pde streetscape

15. Mann Terrace

16. Permit to pick olives

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 1.5 Mb)

1. “The Olive Groves”

This Trail Guide covers three small Parks – Parks 7, 8 and 9 of your Adelaide Park Lands.

Two of them, Parks 7 and 8, are separated by Melbourne Road, which is an extension of Melbourne Street in North Adelaide. The third one, Park 9, lies across Mann Terrace.

Parks 7 and 8 can be thought of as only one Park – and indeed the two together have one English name – “The Olive Groves” (for very obvious reasons).

However, there are two separate names in the Kaurna language for the two Parks. On the north side of Melbourne Road you are in Park 7 which is called Kuntingga meaning ‘kunti root place’. The vegetable “kunti” was described by early German missionaries as ‘the root of red color and taste. which is cooked and eaten by the people of the country ’ .

Park 8, the southern part of the Olive Groves, is much smaller than Park 7 on the northern side of Melbourne Road.

Park 8 is only 1.26 hectares whereas Park 7 is 2.8 hectares, more than twice the size. Park 9 is larger again, at 5.7 hectares.

However, taken together, these three Parks are under 10 hectares in size, which represents only about one-and-a half percent of the total 700 ha size of your Adelaide Park Lands.

Looking southward: with Park 7 in the foreground, Gilberton on the left, lower North Adelaide on the right, and Parks 8 and 9 in the background

Compared to most other Parks within the Adelaide Park Lands, that’s pretty small and you should have no problem getting around all three of these Parks in about two hours. There is a public toilet at Stop #11.

This Trail Guide features a lot of information about olive trees, and the history of olives in Parks 7 and 8, but it also includes quite a few other things.

This Trail Guide also draws your attention to the trees in these Parks that are NOT olives. Here on the corner of Melbourne Road and Mann Terrace is one of the most prominent non-olive trees. It’s a River Red Gum, one of 34 river red gums in The Olive Groves.

A century-old river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) at the starting place of this Trail Guide. Pic: Jaden Lockery

From here, walk northwards, further into Park 7. Stop after about 80 metres when you come to a very large stobie pole – electrical pole.

2. Infrastructure

.

One of the things you can’t help noticing about Park 7 is the burden of infrastructure.

This stobie pole dominates the area – and there are others of the same size along the same line.

Another very large stobie pole, further north in Park 7, towering over the olive trees. Pic: Jaden Lockery

In 2007 the City Council hired a specialist academic adviset to evaluate the historical, cultural and landscape features of all the Park Lands, and make recommendations about how to enhance them.

Dr David Jones produced a mammoth work. It is the starting point for anyone wanting to learn anything about the history and significance of the Adelaide Park Lands. Not surprisingly, Dr Jones recommended that these stobie poles should be removed, because they do not enhance the value of this Park.

Of course that recommendation has not been acted upon.

Dr Jones also mentioned this concrete drainage channel, pictured below. In his view it was “of some engineering merit".

Drainage in Adelaide was a problem for many decades after European settlement. Adelaide and its near-city suburbs are mostly flat and there are many places where water can pool after heavy rain, or leave the ground boggy.

There are several artificial drainage channels in various parts of the Park Lands. Some have been placed underground. Others have been beautifully landscaped, such as the South Park Lands Creek. This drainage channel in Park 7 is the poor cousin. Its date of construction is unclear, but it was probably built in the 1940s or 50s when concrete drainage channels were built elsewhere in Adelaide.

In that era, the idea of landscaping drainage was not even considered. The only thought at the time was that works had to be effective at draining stormwater.

Speaking of infrastructure – if you look across Mann Terrace to the west, you will see Stanley Street in North Adelaide.

The Olive Groves are bounded by two very wide roads - one on each side of these Parks, and each road is a one-way road.

However, for more than 100 years, these two roads were each bi-directional (two-way) roads.

The road on the east, Park Terrace, was the wider road, on the outside of the Park.

Mann Terrace, alongside North Adelaide, was smaller and narrower. Mann Terrace was widened for the first time in 1925.

1935, aerial photo of The Olive Groves, showing Stanley Street cutting across Park 7 linking North Adelaide to Gilberton.

About 1949 the decision was made to convert each of the two roads into one-way roads. Until then, Stanley Street went right across Park 7, as you can see from the 1935 aerial photo above.

From 1949, Stanley Street no longer went across Park 7, but the route it took is still there as a footpath which crosses over the drain, underneath the footpath surface.

A few years later, in the 1960s, Mann Terrace was substantially widened, and at that time the Government separated the residential part of lower North Adelaide from what then became a major road heading north. That also had the effect of narrowing the Park Lands here.

Park Terrace, pictured soon after the road widening in the late 1960s

Now, walk further north until you come to a wooden footbridge over the drain.

3. Olive plantation, 1856

This is a laminated timber bridge built in the 1970's. Dr David Jones in his report in 2007 described it as "of no merit". It replaced an earlier so-called "rustic bridge" built in 1916.

This is probably as good a place as any to start talking about this olive plantation. The history of olives in South Australia is as old as European settlement - exactly the same age, because the first olive tree came on the very first colonist ships.

George Stevenson had the first olive trees, on H.M.S. Buffalo which arrived in 1836 - the year SA was founded as a British colony.

That first olive tree was on private property in the garden of a house on Finniss Street near Frome Road, and it survived until a re-development in the 2010s.

What had been the second-oldest olive tree in Adelaide, planted in the 1840s, also was removed in the 2010s.

2012 pic: realestate.com.au. 2021 pic: Google Streetview

A man named John Bailey also brought olives (6 varieties) shortly afterwards in 1839.

Although he brought six varieties we have only one variety planted here - the European olive. We don't know what happened to the initial trees of the other five varieties.

John Bailey was a horticulturist and botanist who worked at a nursery at Hackney in London, before emigrating to South Australia in 1839 to set up a nursery at Hackney in Adelaide. So, he came from Hackney to Hackney.

His passage was sponsored by the "South Australian Company" the land developers who set up the colony by getting the British Parliament to agree to their venture.

In 1844, Bailey opened his own business called Bailey & Sons, on the corner of North Terrace and Hackney Road - opposite what is now the National Wine Centre and the Royal Terrace Hotel.

John Bailey (1801-1864)

However, he was not always on the right side of the law. It's not clear what went wrong for him because despite the fact that he brought olives with him in 1839, he was in trouble with the law six years later when his company, Bailey and Sons imported olive cuttings without permission. He was charged with illegally planting, cultivating, and distributing them. There might have been some commercial disagreement between Bailey and the South Australian Company.

These illegal cuttings were planted in Bailey's gardens where they flourished and some still exist in a small park at the end of Botanic Street, off Hackney Rd near St Peters College.

Bailey was granted a contract from the Colonial Government (what we would now call the State Government) to fence these parks and plant olives. The contract was worth 500 pounds. The work was completed within the same year - 1856 - so that's how old these trees are.

Some of the original 1856 olives that remain in Kuntingga (Park 7) Pic: Jaden Lockery

John Bailey retired after completing this work, and died eight years later in 1864 of infected kidneys. At the time of his retirement there were an estimated 15,000 olive trees within the Bailey nursery. His son Frederick and grandson John continued in his line of work of botany and horticulture.

From here, walk diagonally across the park, through the olive trees, until you get to a clear patch of grass near Park Terrace on the opposite (north-eastern) side of the Park.

4. The narrowest parks

There is an urban legend that the Adelaide Park Lands were created as some sort of military buffer zone around the city. The Park Lands are so wide (so the story goes) that an advancing army could be spotted in the Park Lands and it would make the city easier to defend from any attack.

This is a furphy, a myth. There is no evidence to support the idea that Colonel Light had this purpose in mind for the Park Lands. There is considerable evidence that the role of public open space was being favourably considered by social reformers in the UK at the time of colonisation, in the mid-1830’s.

Even if, contrary to the evidence, the Park Lands were originally intended for this purpose, then Colonel Light would have messed up here. Most of the Park Lands are about 600 metres wide - e.g. from South Terrace to Greenhill Road is 600 metres. Wakefield Road through the Park Lands is even longer – 800 metres. However these two Parks, 7 and 8, are the narrowest part of the Park Lands. They are only 80 metres wide.

Even before they were narrowed over the years (due to road widening) they would have been no more than 140 metres wide - less than a quarter of the width of most of the Park Lands. Therefore if any 19th century army had wanted to attack, they would have chosen these Parks to launch their attack!

Here on the eastern side of the Park you can see the start of a line of trees that aren’t olives.

On the western side of the Park, it’s almost all olives, but here on the eastern side, all the way from here to the southern end of Park 8, there is an eclectic assortment of trees.

There are three that are most common: River Red Gums, Aleppo Pines and Kurrajong trees. The City Council has advised that The Olive Groves include, in total, 34 River Red gums, but also 19 Kurrajong trees and 15 Aleppo Pines.

The Kurrajong tree (Brachychiton populneus) is native to eastern Australia, but not to the Adelaide region.

It has bell-shaped flowers through the warmer months. In most specimens the flowers are white, but some Kurrajong trees have bright red flowers. This small to medium tree is attractive and highly drought tolerant.

Low maintenance and attractive, the kurrajong is a great feature tree for use in a range of settings, it can reach up to 20 metres in height, but tolerates pruning to limit size.

It has been planted in many locations throughout South Australia, both as a street tree, and also in landscapes and gardens. The dense canopy of glossy green foliage makes it a great shade tree, and the flowers, sometimes streaked with pink or purple add to its visual appeal.

Kurrajong trees flower from late spring to autumn. While flowering, they provide a great source of nectar for bees and other foragers.

Various parts of the plant provided food sources to First Nations people in eastern Australia. The roasted seeds can be eaten, ground as a coffee substitute and used in bread. The tap root is edible, a nutritious vegetable said to be similar to carrot.

Kurrajong leaves

This Park might be the only place in the Adelaide Park Lands where some of the landscaping has been carried out by ants.

As you walk, look out for ant trails, such as these, which in some cases lead to and from Kurrajong trees. The trails are made by the Southern Meat Ant (Iridomyrmex purpureus). The trails are more obvious in the summer months, when the grass has died back. In winter, you might not see them.

The Aleppo Pine (Pinus halepensis) is native to the Mediterranean. It has pine cones and white buds.

Planting them here was suggested in 1880 by forestry expert John Ednie Brown. There are lots of Aleppo pines throughout the Adelaide Park Lands. Like other pine species, Aleppo pines can dramatically change the environmental conditions of an area. The thick layer of pine needles prevent native species seedling establishment. Control methods are the same as other pine species and woody weeds.

Left: Kurrajong (Brachychiton populneus) Right: Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) alongside Park Terrace on the eastern side of The Olive Groves. Pics: Jaden Lockery.

Now walk a bit further south until you come to a river red gum with part of its trunk missing.

5. Red gum fights disease

This river red gum tree is one of 34 river red gums in The Olive Groves. It has what looks like a piece of its trunk missing or folded back.

A City Council arborist, Craig Silcock, has advised that this tree suffered damage sometime in the past. Mr Silcock was unable to say how the damage would have occurred, but a lightning strike was the most likely explanation. The tree has reacted to ‘seal’ itself from possible future spread of disease or decay, by a physiological response forming ‘walls’ around the wounded area.

Arborists use the acronym CODIT, which stands for “Compartmentalisation of decay in trees”.

Trees naturally have three walls within them to prevent decay organisms (bacteria and fungi) from spreading. One wall prevents decay organisms from travelling up through the trunk of the tree. A second wall prevents the organisms travelling inwards from the bark to the centre of the trunk.

A third wall prevents organisms getting around the trunk in a radial or circular direction, around the trunk.

What you are seeing here is an unusual fourth wall – a response to injury. This wall is a new barrier that restricts movement of decay into tissues formed after the wounding. The cells in this wall contain chemicals that are toxic to decay organisms. This fourth wall is the strongest wall, capable of confining decay to tissues formed prior to wounding as long as the wall is not broken by another wound.

While you are here - look across the road to see the historic Gilberton Chapel, which dates back to 1910.

The former Gilberton Chapel, at 11 Park Tce Gilberton. Pic: www.commercialrealestate.com.au

Its foundation stone (laid by a Mrs W.S. Thompson) reads “Thompson Memorial Congregational Church”. In 1977 the Church and attached hall were purchased by the Pentecostal Church Society for $40,000. The hall was regarded as unsafe and was demolished in 1982, at which time the Church was refurbished.

In recent decades it was hired out as a function centre for weddings, business meetings, small conferences and church services. It was sold in 2019 as an office building, fetching $997,000. It’s since been tenanted by the ‘Adelaide Bridal Collective’.

From here, walk southward and cross over Melbourne Road, to enter Park 8.

6. Olive oil industry

This Park is called “Parngutilla” in the Kaurna language, which means 'parngutta root place', referring to the potato-like root which was eaten by Kaurna people.

In between Melbourne Road and the bicycle/pedestrian path is a large Stone pine (Pinus pinea) with an umbrella-shaped canopy.

Stone pine (Pinus pinea) on the edge of Melbourne Road, at the northern end of Parngutilla (Park 8) Pic: Jaden Lockery

The Stone pine (Pinus pinea), like the Aleppo Pine, originates in the Mediterranean region. It has an unusual canopy shape. With time, it forms a flat topped tree with a shady canopy, like an umbrella. It is one of the pines that is harvested for its edible pine nuts. There are several Stone pines in various locations of the Adelaide Park Lands – but far fewer of them than the more common Aleppo Pines.

Until 2024, there was a second Stone Pine just further south. It was very large, bent over, leaning to the west. City Council arborists removed it in 2024, because of the danger that it might fall.

A former second Stone pine tree in Park 8. It was removed in 2024.

Before you head further into the olive groves of Park 8, this is an opportunity to go back in time to learn about not just the olive plantation, but the emergence of an olive oil industry in Adelaide.

The Trail Guide mentioned earlier the founder of these olive groves, John Bailey. Mr Bailey had his own olives planted well before the plantations in these Parks. He also had a business associate called George Francis, who had the idea of pressing Bailey's olives to make olive oil. Messrs Bailey and Francis did that, and some of the olive oil was sent to the 1851 "Great Exhibition" in London - in the famous newly-built Crystal Palace.

The South Australian olive oil got an honourable mention at the Great Exhibition so you would think it must have been good for business. But no. Nothing came of the SA olive oil industry at that point. Olives were still growing and the plantations were expanded over the following years but no more olive oil was produced for another 20 years.

The olive oil industry in SA came to life in the 1870s but at that time it was not the City Council and not these olives that drove the establishment of a South Australian olive oil industry. Rather, it was the plantation near the old Adelaide Gaol where the olive oil comeback was launched, and the proximity to the Gaol was no coincidence.

Location of a 19th century olive grove in Kate Cocks Park (Park 27) that survived for more than 160 years, until 2024. Most of these trees were removed in May 2024 to make way for a new Women’s and Children’s Hospital and an eight-storey car park.

The Superintendent of the Gaol, William Boothby, extended the original olive grove, from about 1,100 trees in 1862 to over 5,000 trees by 1880. And he had a ready workforce. He put prisoners to work picking olives, starting in 1870.

The Adelaide Gaol had the first commercial olive press, not just in SA, but anywhere in Australia. The Gaol olives continued to be supplemented by fruit from the other Council groves, such as this one. And it was not just prisoners picking them. In the 1870s and 1880s there were also olive pickers who were brought from the nearby Lunatic Asylum, the Destitute Women’s Asylum in Kintore Street, and orphans.

In those days olive oil was not for salad dressing and frying fish. Until petrol and motor oil became widely available in the 20th century, olive oil was used in industry and pharmaceuticals.

Belatedly, in the late 1880s, the City Council decided to get in on the olive oil act. About the turn of the century, from 1897, the City of Adelaide was selling 2,000 litres or more, per year, at what were very good prices (for that era). Seven or eight shillings per gallon was the going price. Allowing for inflation over more than 120 years we are talking about roughly $5.30 per litre. That was the wholesale price that the City of Adelaide received. That would have been more than $10,000 per annum, in today's money, flowing into the City Council's budget.

A new city gardener, August Pelzer from 1900 continued the olive oil production and re-planted trees where necessary. The City eventually stopped using wholesalers and marketed its own 'City of Adelaide' olive oil, using the label pictured above. However, City of Adelaide olive oil has been unavailable for more than 100 years!

Now keep walking south, until you come to another dirt pathway that crosses Park 8.

7. A treasure or a weed?

We know that these olive trees are more than 165 years old, and you would have noticed many of them are bearing fruit, albeit quite small fruit. So perhaps you are wondering, how old can they get?

European olives are VERY long-lived. The oldest olive tree in the world is supposedly on the island of Crete, in the Mediterranean, where its age is estimated to be at least 2,000 years and perhaps up to 3,000. Many in Europe are over 1,000 years old. 500 years is quite common.

There is archeological evidence that olives were grown in Crete as early as 3,500 BC. That is, more than 5,500 years ago. The Greeks believed they were sacred and there are numerous references to olives in the Bible.

Even today an olive branch is a symbol of peace and plenty. The phrase “extending an olive branch” means offering peace.

Olives typically do best in ‘Mediterranean’-type climates with long, hot dry summers with low humidity and winter rain and cold. If there is not enough chilling in winter then there will not be as many flowers, and so fewer fruits.

However, olives are also considered to be a real problem, especially here in South Australia.

A fruiting tree in The Olive Groves

In South Australia, feral olive trees are a declared “invasive species” or a weed. They spread very easily – because birds eat the olives and carry the seeds into bushland. It’s very difficult to dig out olive trees once they are established.

Feral olives occur throughout the Mount Lofty Ranges, with severe infestations occurring around Brown Hill Creek, Shepherds Hill, Sturt Gorge and Onkaparinga Gorge.

In bushfires they are a real danger to firefighters. They make fires worse, because they burst into a big ball of flame like an explosion.

There is no simple solution to the problem. If you have an olive tree, it helps if you can collect every single olive to prevent the birds taking any and spreading the seed. And on this Trail, feel free to pick up any olives that you might see on the ground.

On your own property, if you are not going to harvest olives, then pull out the tree – although that is easier said than done! In our now more fragile world we don’t want introduces species such as olives to make it even harder for indigenous flora and fauna to cope. See more advice here: https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/landscape/docs/hf/Feral-olive-fact-sheet_2023-11-22-041353_slan.pdf

At the final stop on this Trail you will learn about harvesting Park Lands olives with a City Council permit.

For now, walk further south until you come to the two Moreton Bay fig trees at the southern end of Park 8.

8. Diversity of other trees

Port Lincoln wattle

There are 594 olive trees in the Olive Groves. There are also 34 River Red gums, 19 Kurrajong tree and 15 Aleppo Pines.

On this Trail, you have already passed a magnificent Stone pine (pinus pinea) in the east of Park 8, near Melbourne Road.

But there’s also a number of other trees and most of them are concentrated here in the southern portion of Park 8 next to the O’Bahn busway.

eight Port Lincoln wattles, also known as Flinders Ranges wattle or willow-leaf wattle (Acacia iteaphylla) near the southern end of Park 8;

three yellow gums (Eucalyptus leucoxylon) also in the far south of Park 8

a single example of Norfolk Island Hibiscus (Lagunaria patersonia) in the southern part of Park 8;

a single example of Canary Island Pine (Pinus canariensis) in the south-east part of Park 8;

a single example of sugar gum (Eucalyptus cladocalyx) towards the south of Park 8;

a single example of 'Golden wattle' (Acacia pycnantha); and

a single example of a relatively young lemon-scented gum (Corymbia citriodora).

Before you leave this spot, take a closer look at one of the eight willow-leaf wattles. This species is unusual among acacias in that it actually has what look like proper leaves.

Many species of Acacia have “phyllodes” rather than leaves. A phyllode is defined as a leaf whose blade is much reduced or absent. The slender leaves of this bush are blue-green in colour and arranged alternately, almost at right angles to the stems. The perfumed flower heads are produced in clusters of pale yellow balls which contrast pleasingly with the foliage. The buds are attractively enclosed by conspicuous pale, brown-tipped bracts. The flowers are followed by masses of flattened blue-green seed pods which become brown when mature.

It flowers intermittently throughout the year with a peak flowering period in spring. It is versatile in its habit growing to a height of two to four metres, with some forms becoming upright, whilst others are pendulous and bushy.

The Park Lands Management Strategy envisages turning these Parks into a “formal park setting” (whatever that means) and installing more walking trails and interpretive signage. There are three signs already.

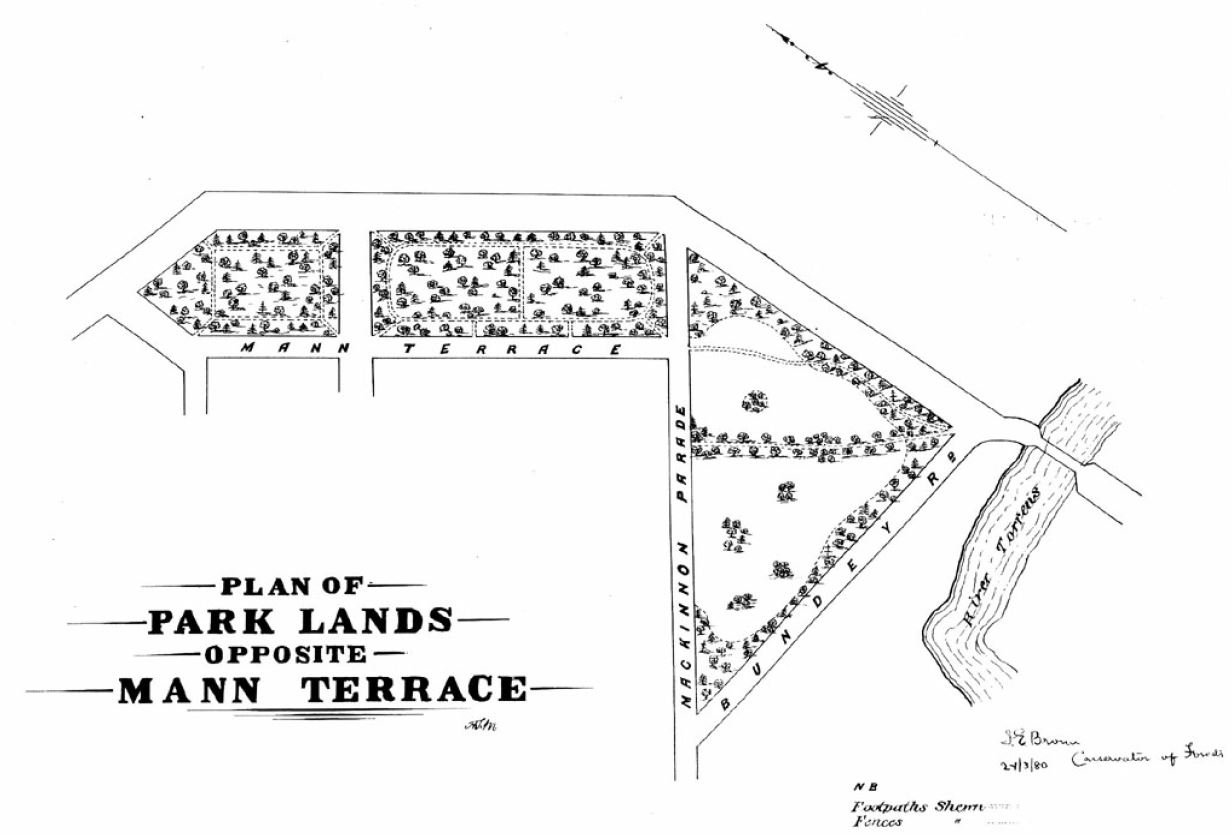

This plan has echoes of one of the earliest plans for this Park. In 1880, forestry expert John Ednie Brown envisaged walking trails around the olive groves, but this was not put into practice.

John Ednie Brown’s 1880 plan for Parks 7, 8 and 9, with walking trails around and between the olive trees, that were already long-established.

From here, wait for a break in the traffic, then walk carefully across Mann Terrace to enter Bundey’s Paddock / Tidlangga (Park 9) across the road.

Park 9 naming

This small wedge of Park Land is only 5.7 hectares which means it comprises less than one per cent of the total area of the Adelaide Park Lands.

Nevertheless it is a very popular area for local residents of North Adelaide and the suburbs immediately to the east, including Gilberton and Walkerville.

Tidlangga is a Kaurna language name, which means ‘tidla root place’, referring to a bulbous root eaten by the Indigenous people.

Due to its location close to the river and other known corroboree grounds, in pre-colonisation times this area may have been used as an encampment for the local Kaurna people.

Its other name, Bundey’s Paddock, has been used (informally) since the 1880’s in honour of a former mayor of Adelaide in the 1880’s, William Bundey.

The name was formally assigned to the Park (by the City Council) only as recently as September 2017.

Tidlangga is a Kaurna language name, which means ‘tidla root place’, referring to a bulbous root eaten by the Indigenous people.

Adelaide City Council is proud of this park because, they say, it demonstrates the way urban planning can both encourage and respond to community activity.

William Bundey and his family arrived in South Australia in 1848, when he was aged only 22.

He died in 1889, at the age of 63, just three years after ending his term as Mayor. He is buried in Walkerville Cemetery. He died of a heart attack minutes after having proposed a toast at a wedding reception being held in the North Adelaide Institute in Tynte Street. Mr Bundey was a stalwart of the Methodist Church on Melbourne Street (now the Elders Fine Art Gallery) and lived on Mackinnon Parade, although records don’t indicate in which house.

It’s assumed that he kept horses and/or cattle across the road in this Park, hence it became known in his lifetime as Bundey’s Paddock.

Park Lands Trail

Walking south along the eastern edge of Park 9 you are on a shared-use bicycle and pedestrian path.

"Shared use" means all users should keep to the left, and cyclists should use a warning bell when coming from behind pedestrians.

Cycling is a convenient way to explore the Park Lands.

This path is part of the Park Lands Trail that loops around the entire Park Lands.

The Trail connects each part of the Adelaide Park Lands but requires you to cross many roads and railway lines.

A local businessman, Jason Redman has gathered support from a wide cross-section of business, community and sporting organisations for a plan to do away with all these various crossings, constructing tunnels or bridges so that the entire Park Lands Trail can become an unbroken walking cycling or running trail. Mr Redman has called the idea the Adelaide Recreation Circuit.

Jason Redman. Pic: https://www.facebook.com/adelaiderecreationcircuit

In the 2022 State election campaign, the Labor Party promised that in Government, it would investigate the feasibility of the Adelaide Recreation Circuit.

Twice per year the Adelaide Park Lands Association holds a 'Park Lands Loop Collective' walk using the 15 kilometre Park Lands trail to loop around the City.

A longer loop of more than 19 kilometres is possible if you take a route that includes the Park Lands on the northern side of North Adelaide.

With its original broad, flat streets and a growing network of dedicated cycling paths, Adelaide is made to be seen from a bike.

Now, walk further south and stop at the corner of Mann Road and Bundey’s Road.

10. South-east corner

The two largest trees near the corner of Mann Terrace and Bundey’s Road are a Himalayan Cypress, and a massive sugar gum.

The Himalayan Cypress (Cupressus torulosa). There are not many of this species in the Adelaide Park Lands.

A brick, gable-roofed maintenance shed formerly located on this corner was used for decades by Prince Alfred College, and its Old Collegians Association.

When first constructed it housed a tractor, but later was used for storage of sporting equipment associated with the College’s use of the Oval.

A former maintenance shed near Park 9’s south-east corner. It was demolished in 2023, after construction of new sporting facilities, a few hundred metres west in this Park.

From this point, look across Bundey’s Road to the Hackney Road bridge over the River Torrens.

HACKNEY BRIDGE

The River Torrens is not within Bundey’s Paddock/ Tidlangga (Park 9) but it is, of course, an important part of the Adelaide Park Lands.

During the nineteenth century the river supplied Adelaide with drinking water.

Strangely, to protect the water supply swimming was prohibited but cattle were allowed to drink and muddy the waters.

Despite the swimming ban, many people swam in the River close to this spot.

Just west of the bridge, one swimming spot, known as the Death Hole, was the site of many drownings, mainly of young boys.

This stretch of river was also exploited for its natural resources of sand and limestone.

Early Park Land maps show a ‘Sand Carters Road’ from the river to Bundey’s Road, across the adjacent Park 10..

Sand-carting was so common it was eventually licenced to raise revenue.

Ironically, this revenue was used in the early 1900s to repair the damage done to the riverbank in the first place by the sand carters.

Sand carters working on the banks of the River Torrens, approximately 1912. Pic: State Library of South Australia B 62185

Now walk westwards, into the Park towards the playing fields and stop at the sports building.

11. Sports facilities

From the earliest days of European settlement, the Adelaide Park Lands have hosted numerous sports.

By 1920, as many as 250 permits were issued for clubs wanting to play sport in the Park Lands.

A controversial topic for many was the playing of sport on Sundays.

In 1939, under pressure from a deputation from members of Protestant churches, the council banned organised sports from the Park Lands on Sundays.

It took another 28 years, until 1967, for that ban to be reversed.

This oval was levelled for use in 1914. This oval is licensed to the Prince Alfred College, and its Old Collegians Association.

The Park 9 oval, pictured in 2018 before construction of the new clubrooms

This means that PAC and its Old Collegians have the first right of use of the oval. The public can use the area when the licencees aren’t using it.

In November 2017, the City Council approved (in principle) the building of a new 375 square metre clubroom facility to replace TWO old facilities.

It approved a new building to replace both a toilet and change room block, and a metal maintenance shed that was on the corner of Mann Rd and Bundey’s Rd.

The new building was required to include “a small community space of 75 sqm and public toilets to service the adjacent community activity hub.”

It took a further three years, until late 2020, for formal plans to be submitted, for a building of 410 square metres, slightly larger than the Council’s in-principle approval.

The building plans also included a bar and viewing deck, along with a new road into the Park, to new building location closer to the centre of the Park. Construction commenced in June 2022, and was completed by March 2023. Demolition of the two older buildings was carried out shortly afterwards.

The planning of the new building and negotiations over its proposed usage, demonstrates the ever-present tension faced by the City Council in its management of most of the Adelaide Park Lands.

Sporting or recreational clubs and schools often seek to build amenities on Park Lands and their plans must be set against community expectations of Park Lands as open, public and green spaces.

From here, walk westwards about 75 metres along the edge of Bundeys Rd until you come to this metal gate which prevents cars driving into the park.

Turning right here, into the Park will bring you to the start of the bushland trail.

12. Bushland trail

The entrance to the bushland trail is framed, quite literally with a wire-and-post fence and a wooden gate.

Several more of these wooden frames on the trail are adorned with metal dragonflies. How many can you count?

In contrast to the previous historical neglect of this Park, this area is now a flourishing native vegetation site, providing homes for native bird and animal life, especially possums, which are often seen around twilight.

The common bird species here include lorikeets, magpies, corellas, galahs, sulphur-crested cockatoos, ibis, banded lapwings and noisy miners.

Wind your way through the bushland trail until you emerge at the “community hub”

To your left, on the MacKinnon Parade footpath you can see two old metal fence posts that have been left in place as a reminder of a bygone era. They are more than 100 years old.

These are wrought iron gate “straining posts” and if you look carefully you can see they are embossed with the words “Francis Morton’s Patent No 1 Liverpool” on each post cap. These are rare surviving examples of the wrought iron fencing that was acquired by the City Council in the 1910s to fence Park Land blocks.

Now, walk up to the rocky ground in the playspace. Stop before you reach the tennis court.

13. Playspace & community hub

This part of Bundey’s Paddock / Tidlangga includes a sandy petanque piste, tennis courts, playground, sandpit, barbecues and picnic tables.

It is frequently visited by families—in fact, there are over 3,000 visits to this park every year.

Personal trainers often bring their clients here for workouts, and you can often see ad hoc usage by small groups of young men (usually) at the basketball facilities.

The first children’s playground in the Adelaide Park Lands was established in 1918, off South Terrace in Park 20.

Today there are ten playgrounds in the Park Lands.

This “adventure” playground was installed in 2016, by a firm called “ProLudic” contracted by the City Council.

It replaced a former playground of the old fashioned swings and metal slippery dips type that had been further along Mackinnon Parade for many decades.

This one incorporates the principles of adventure and exploration that underpin planning of play areas in kindergartens and schools these days – and children love it.

The rock fields are intended to encourage children to practice their balance on an uneven surface.

The existence of the playground has made this spot a favourite site for children’s birthday parties!

Photos: ProLudic

From here, walk back out to the street, to see the MacKinnon Parade streetscape.

14. MacKinnon Pde streetscape

MacKinnon Parade is named after William Mackinnon (1784-1870), one of the foundation SA Commissioners appointed during 1834 to help administer the new colony. He benefitted from the slavery trade (taking slaves from Antigua). Somewhat incongruously, he was a strong supporter of the RSPCA, and also a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Houses and apartments

50 Mackinnon Parade was originally called Keith House, after Frances Keith Sheridan, who lived there with her family, and ran a school there with her daughters.

Her elder daughter was Alice Frances Keith Sheridan (1844 to 1922). Alice Sheridan lived all her adult life in "Keith House", the last twenty years or so alone with her dogs, shunning human company. Despite owning considerable wealth, she did not employ any help apart from occasional visits from a gardener, and she spent little on herself. Alice Sheridan had a genius for languages, having a considerable knowledge of Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, German, Spanish, Italian and Danish. It was through her knowledge of Danish that she was able to publish a book of Hans Christian Anderson stories which had not previously appeared in English.

When she died she left around £30,000 to the Adelaide University, fulfilling an agreement made with her sister Violet that whichever of them survived should enjoy the income from family property in the city ("Globe Chambers" on the corner of Grote Street and Victoria Square), then leave the land and buildings to the University, to be used for the "advancement of medical science, in memory of their parents." Among her papers was a request for the University to take care of the graves of herself and the members of her family in the West Terrace Cemetery.

"Keith House" was left to the North Adelaide Institute, and in 1925 it became the Keith Sheridan Institute.

50 Mackinnon Pde in 1925. Image: State Library of South Australia B2443

In 1963 the building became the Sheridan Theatre, home of the Adelaide Theatre Group. The Theatre closed in 1985 and the builidng has since been a private residence.

Alice Frances Keith Sheridan made another bequest. After she died in 1922 a further £2,000 from her estate was paid to the Royal Adelaide Hospital to build a kiosk, to be operated by the Adelaide Hospital Auxiliary. The building, an octagonal structure with a dome roof, was opened in 1925. It’s still there, known as the Sheridan cafe, off North Terrace in what the State Government calls “Lot Fourteen”.

The Sheridan kiosk at the former Royal Adelaide Hospital in 1962 (left) and in 2022 (right)

Back on Mackinnon Pde, if you look further west, on the far side of Provost Street, you can see two blocks of red brick apartments. These two block might not seem unusual but they were relatively important in Adelaide’s 1970s red brick modernism school. These “Garden Terrace Apartments” at 55-57 MacKinnon Parade were designed in 1974 by the well known architect and football player, Ian Hannaford (who died in 2022). They were described in an architectural magazine at the time, as “a new medium density housing concept”.

Next to the Sheridan cottage are architect Robert Dickson’s two linked townhouses, which were revolutionary when built in the early 1960s. The two houses were built together in order to get around Council regulations which did not allow subdivision of such a small block, with the owners hoping they could subdivide later. They were the first town houses to be built in North Adelaide.

In the 2010’s these two townhouses were both substantially altered. Each of the owners wanted to open up the properties to the Park Lands with balconies, rather than having just private outdoor living space, which the houses were designed to maximise. To accommodate the opening up, what was at the time the largest and second-oldest olive tree in South Australia (at the front of #46) was chopped down.

2012 photos: realestate.com.au 2021 photos: Google Street view

Other houses along MacKinnon Parade feature blue plaques which explain some of their history.

There is a pair of Victorian 1880s single-fronted masonry residences with highly decorative cast iron detailing. In recent years they have been linked to form one residence.

Another pair of nearby houses appear to be conventional double-fronted villas, but they are unusual (for their 19th century period) in having the main entrances to the side of the house.

Now, turn around and look back towards Park 9 to see the planter boxes on the edge of the community hub.

In recent years local residents, with the support of the City Council, have tried to develop some orchard and garden activity.

The effort initially consisted of citrus trees in raised beds on the Park side of the road, and a vegetable garden on the verge (although this was left dormant after a while).

The Council continued this initiative by planting fruit trees and herbs near the barbecues in the community hub.

Fruit trees are included in these series of planter tubs placed alongside the Park edge on MacKinnon Pde. Pics: Google StreetView

Now, walk east to the end of MacKinnon Parade.

15. Mann Terrace

This corner of North Adelaide wasn’t always quiet.

Up until the 1970s, MacKinnon Parade and Mann Terrace were through roads and it was possible to drive straight across into Gilberton.

That changed when the O-Bahn busway was built in the 1970s.

Before the road changes, there were tennis courts along the eastern edge of the Park, as you can see in this aerial photo from 1936.

Photo: City of Adelaide archives

In the 1860s and 1870s olive trees were one of the most widely planted trees in the Adelaide Park Lands, because of their fast growth and usefulness.

Although the olives are gone from this Park, you don’t have to look far to see them.

From here, watch carefully for a break in the traffic, and walk back across Mann Terrace, to re-enter Park 8, and find a quiet shady spot among the olive trees.

16. A permit to pick olives

As you travel around the Park Lands you will see olive trees that are of a similar vintage to these ones. They might not be quite as old, but pretty close. Most olives in your Park Lands were planted in the 1860s or 1870s.

Some parks have only two or three surviving from that era. However there are substantial olive groves still existing in the two Parks either side of Wakefield Road, i.e. King Rodney Park / Ityamai-itpina (Park 15) and Victoria Park / Pakapakanthi (Park 16).

Newly-planted olive trees, off East Terrace in Park 15, pictured in 1880. Image: State Library of SA, B-9420

The other major heritage olive orchard is in Kate Cocks Park - near the Old Adelaide Gaol and next to Bonython Park where the Police "grey" horses are kept.

There is nothing to stop you picking up olives from the ground, but you are not allowed to pick olives on this Trail, unless you have a permit from the Council. Fortunately it’s easy to obtain a permit – just click on this link and insert your name and email address. The permit applies to most olive trees in the Park Lands, not only these Parks 7 and 8.

Size comparison: commercial green olives compared to black olives harvested in The Olive Groves (Parks 7 and 8). Pic: Jaden Lockery

To obtain your personal permit, you will have to tick the box, to agree to all these conditions:

Take care and discretion while collecting olives and avoid disturbing residents and other users of Park Lands;

Before leaving an area, clear and carry away all litter, branches, twigs and leaves that have fallen while collecting olives;

Ensure equipment used in the olive collection does not create a risk to the general public;

Take the necessary precautions to avoid damaging trees (trees must not be shaken, beaten and no branches are to be removed);

Vehicles and trailers must not be driven onto or parked on Park Lands;

Follow all reasonable and legal verbal instructions from Council Officers or SA Police;

Must not, under any circumstances, climb into a tree when collecting olives; [However you can use a ladder];

Indemnify the City of Adelaide for any liability in respect to injury, loss or damage arising out of or in connection with the collection of the olives or its produce;

Be responsible for the storage and care of all materials and equipment used; and

Do not pick olives from any trees that are in garden beds.

Most importantly the permit EXCLUDES the olive trees near the Police barracks in Kate Cocks Park, near Bonython Park in Park 27. That spot is where SA Police keep their horses and there are signs there advising you not to enter the horse paddock, both for your own safety and their concerns for the police horses. However, that is not relevant here in Parks 7 and 8.

From here, walk back towards the starting point at Melbourne Street.

Optional: download and print a tri-fold leaflet, i.e. a double-sided single A4 page, with a brief summary of this Trail Guide: (PDF, 1.5 Mb)

All of our Trail Guides and Guided Walks are on the traditional lands of the Kaurna people. The Adelaide Park Lands Association acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future traditional custodians and elders of these lands.