by Sorrel Pompert Robertson

Our series of stories, Know Your Park Lands Art, guide you through various creative displays within your Adelaide Park Lands.

Five origami-like boats make up Shaun Kirby’s Talking Our Way Home installation on the River Torrens / Karrawirra Pari.

The installation in Tarntanya Wama / Park 26 is inscribed with the wording of letters written to loved ones by 19th and 20th century migrants here.

The artwork also tells the history of Adelaide: of Indigenous culture and history dispossessed, of migrants travelling thousands of kilometres for the uncertainty of life in a new country, and of the wave of working holidaymakers that are now making Australia their temporary home.

The letters of 19th and 20th century migrants are fired onto the glass structures of ‘Talking Our Way Home’. Photo: Sorrel Pompert Robertson.

Installed in collaboration with the Indigenous Kaurna people in 2005, the boats indicate the dark history of displacement, but also provide a more hopeful message of cultural exchange.

The River Torrens / Karrawirra Pari was historically a site of importance to the Kaurna people. The river was their food source, the site of secret men’s initiation ceremonies, and the land nearby was where a sacred ‘kangaroo rock’ – used for the Red Kangaroo Dreaming – was found and promptly excavated by European settlers for building projects. The site is now occupied by the Adelaide Festival Centre.

The Adelaide Festival Centre lies on the site of the historic Sacred Kangaroo Rock and the Elder Park Migrant Hostel. Photo: Keir Gravil.

Lying on the shore, just metres from where the boats float, are two contrasting quotes which highlight this disconnect.

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” says Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstien.

The Kaurna people reply: “Ngaiera karralika kawwingga taikutti yerra kumanendi”; roughly translated to: “The sky and the outer world are connected in the waters and the two become one.”

Inscriptions from Wittgenstien and the Kaurna people accompany the boats at the shore. Photo: Sorrel Pompert Robertson.

Here, two world views are at odds: one defined by the rigidity of language, and the other, by a spiritual connection to country.

With the boats, Kirby combines these two world views with the fixed language of letters fired onto the glass structures, which lay in a fragile limbo between sky, water, and land.

As Catherine Speck, a researcher from the University of Adelaide, said in her review of the project: “It is an overt act of cultural exchange and negotiation through language.”

Migration is at the core of this piece’s story, though.

Shaun Kirby was born in London in 1958 and moved to Adelaide with his parents during the mid-1960s as part of the ‘Ten Pound Poms’ scheme – a policy created in 1945 to drive migration from Britain in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Shaun Kirby migrated with his parents to Adelaide in the mid-1960s. Photo: Thylacine.

Half a million displaced Brits moved to the sunny land of Australia through this scheme, making it one of the largest planned migrations of the 20th century.

The towns of Elizabeth and Whyalla particularly became hotspots for these populations, and by the mid-60s, British citizens outnumbered Australian-born residents in Elizabeth as they set about working at industrial sites and fruit farms.

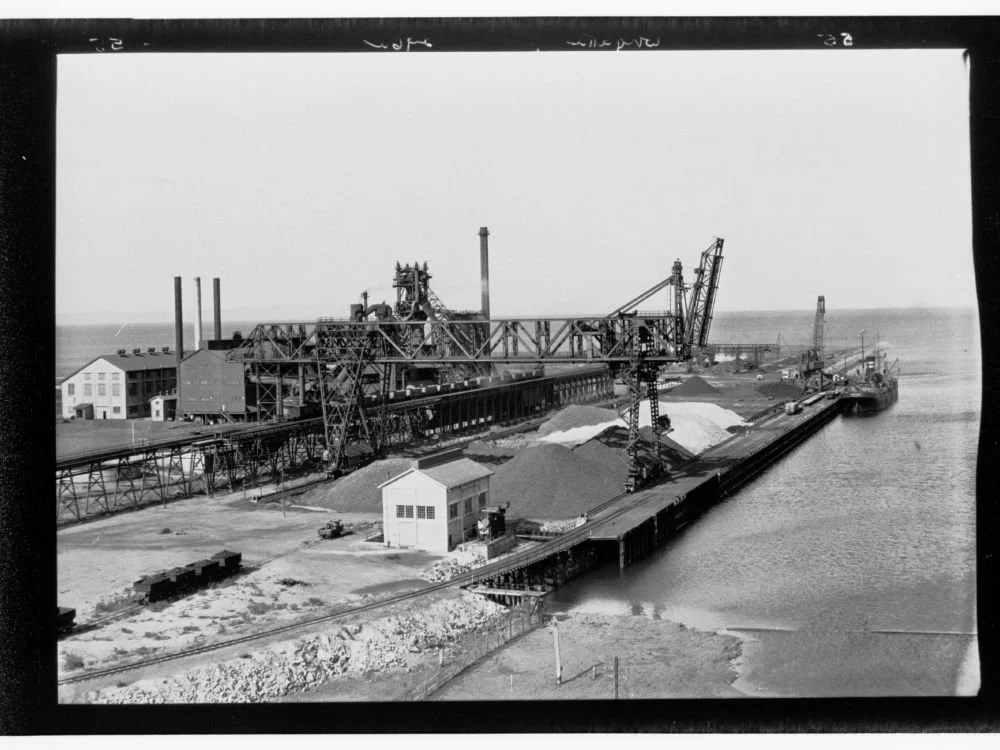

Industrial work in Whyalla was a popular occupation for migrants. Photo: South Australian Government Photographic Collection (GN15254).

Sixty years later, the South Australian government has taken pains to recreate this influx of Brits, enticing young backpackers to work in the fields and hospitality again under the Working Holiday scheme (I am one such example!). There are currently over 1.1 million British citizens residing in Australia.

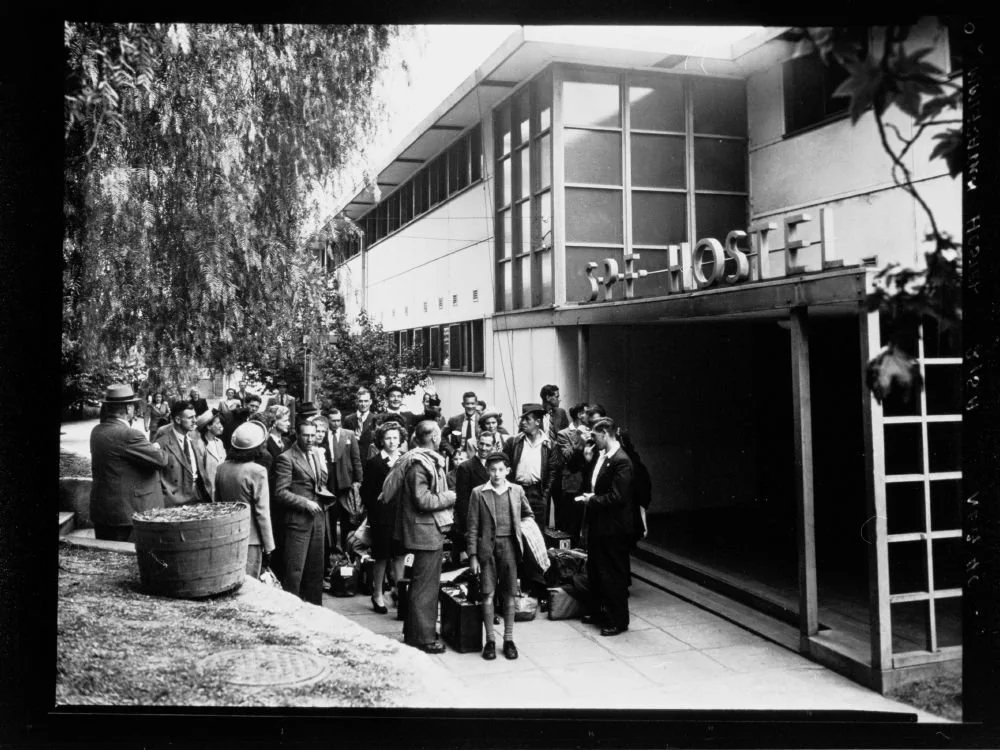

When Kirby and his family arrived, they lived in the Elder Park Migrant Hostel – one of the 12 government-run, migrant hostels operating at the time, which was also on the site where the Adelaide Festival Centre now sits.

With little privacy and shared facilities, this residence was largely used as a short-term accommodation before residents moved onto more permanent lodgings. The life of the migrant was clearly fraught with instability and transience.

Migrants arriving at the Elder Park Migrant Hostel. Photo: South Australian Government Photographic Collection (GN14994).

Kirby gives a strong sense of this uncertain migrant lifestyle through his work. The Talking Our Way Home installation is designed as if by a child, folding paper into a toy boat.

It’s not hard to feel the fragility and uncertainty of a child’s experience, standing there on the site of the hostel, overlooking the boats on the river.

It’s also easy to imagine the turbulence of the migrants’ journey: travelling thousands of kilometres across stormy seas on a month-long journey to reach their new home.

As Kirby said in his interview with Speck, the boats are “sweet but lonely presences out there”. It is the migrants’ condition to be surrounded by people but to be alone at sea.

“Sweet but lonely presences.” Kirby’s boats shimmer on the River Torrens / Karrawirra Parri, towered over by the Adelaide Oval, in Park 26. Photo: Sorrel Pompert Robertson.

Yet, there is a sense of hope to the installation. The sturdiness of the steel-and-glass structures, coupled with the handwritten words of the migrants, indicate the grounding of identity in the written word and in belonging to a new community.

Kirby’s art project was well-received when it was unveiled, seen as an “enlightened” approach to public art. It provided a new aesthetic to draw Adelaide away from its reputation as the ‘City of Churches’ and towards a more sophisticated, urban space.

Reminiscent of Kaurna culture, historical British migration, and indicative of a new wave of Adelaidean culture, these boats are a summation of the story of this city.

Despite that weight of history, these seemingly fragile boats are undeniably strong and remain bobbing on the River Torrens / Karrawirra Pari, best viewed from Elder Park.

Shining like lanterns at night, these boats are a beautiful addition to Adelaide’s riverside at all times of day. Photo: Thylacine.

For more articles in our Know Your Park Lands Art series, head here: https://www.adelaide-parklands.asn.au/know-your-park-lands-art.

Sorrel Pompert Robertson is a Falkland Islander who has been travelling around Australia on a Working Holiday visa for the past year and a half.

She’s recently settled in Adelaide and with her background in wildlife conservation and communications she’s enjoying supporting the Adelaide Park Lands cause for the short time she’s here.